Found jewellery and a unique coin: Three women were buried here during the Viking Age

On a small rocky knoll on the west coast of Norway, archaeologists have uncovered a rich burial ground from the Viking Age.

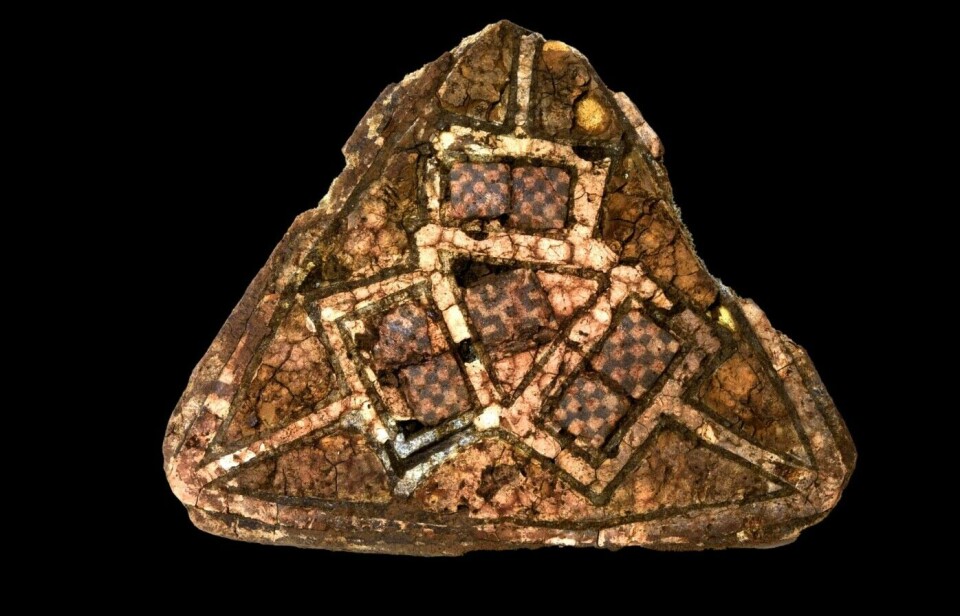

A coin and a brooch with textile fragments.

These were the items the metal detector enthusiasts found when they searched the Skumsnes farm in Fitjar on the west coast of Norway last year.

Now, archaeologists from the University of Bergen confirm that the items came from a Viking Age burial site. They believe there may be around 20 graves.

“Many of the buried individuals were adorned with fine jewellery. It is remarkable to find a burial ground with such well-preserved artefacts,” says archaeologist Søren Diinhoff from the University Museum of Bergen.

“From a research perspective, this is a small treasure trove,” he says.

Three of the graves were excavated this autumn.

Three women from a large farm

The graves belonged to three women who lived during the early Viking Age, in the first half of the 9th century.

At that time, there was a large farm at Skumsnes. It probably belonged to a local or regional king in western Norway.

“Below the level of royal estates, we find strategic farms like Skumsnes,” says Diinhoff.

Its location along the coast probably made it attractive to travellers in need of a safe harbour.

“On behalf of the king, shelterwas provided to passing ships, which likely generated additional income,” he believes.

This explains why the graves are richer than those that are more commonly found.

46 glass beads and 11 silver coins

One woman was buried in a natural crevice in the rock, which was then covered with stones.

This was not such an unusual way to bury people along the coast during the Viking Age, according to Diinhoff.

The woman was buried with costume jewellery and brooches, the characteristic oval brooches that Viking Age women used to fasten their apron dresses.

Several of the pieces of jewellery originated from England or Ireland.

The other woman was of higher rank.

Her grave contained stones arranged in the shape of a boat. Inside the stones were boat rivets.

A four-metre-long boat accompanied this woman into the afterlife.

This grave also contained oval brooches, other costume jewellery, and a necklace made of 46 glass beads and 11 silver coins.

The most remarkable find

One of the coins is a very rare variant from the Danish Viking towns of Hedeby or Ribe. It was made in southern Denmark during the first half of the 9th century.

“That coin might be the most remarkable find here,” says Diinhoff. “I plan to have it tattooed this winter.”

The other coins appear to be Carolingian silver coins. These also date from the first half of the 9th century but originate from the Frankish Empire. This suggests the woman had connections to the continent.

“Both of these women had contacts outside Norway. It's probably no coincidence. Perhaps they came from abroad and married into the local community,” Diinhoff speculates.

Textile producers

But the woman in the boat grave was not only buried with beautiful jewellery.

She was also equipped with wool shears, a hetchel, a spindle whorl, and a weaving sword – items needed to produce textiles. The archaeologists believe she was in charge of this work on the farm.

“Textile production was prestigious. Farms that made fine clothing held high status,” says Diinhoff.

Finally, the woman had a bronze key with her in the grave.

“This also indicates that she held a role as the head of the household,” he says.

Why wasn't she buried wearing the jewellery?

None of the graves contain any human remains.

“That's the problem with western Norway. The soil here consumes the bone remains,” says Diinhoff.

The glass beads and coins that formed a necklace in this woman's grave were found atop a dark organic mass. Archaeologists wonder if they might have been inside a leather pouch.

But why wasn't she wearing her jewellery when she was buried?

Is it possible that she was never buried at all? Archaeologists speculate whether the grave might be a cenotaph – an empty grave that serves as a memorial.

Because there is one more thing.

“It's a small detail, but it's insanely interesting,” says Diinhoff.

In the middle of the boat grave, there was a stone marking the mast of the boat. When the archaeologists turned it over, they saw that it resembled a ‘vulva stone’ – the stone looked like female genitalia.

“That the stone resembles a woman is no coincidence. It's so obvious,” says Diinhoff.

Was it placed there to symbolise the woman who may not have been buried in the grave?

This theory offers a possible explanation for why the objects here were not found on a skeleton.

More than expected

The third grave has not been fully excavated. The archaeologists simply found too much in the first two and ran out of time.

However, they secured a number of objects, including 20 beads and the remains of a piece of silver-plated jewellery.

They have also identified two additional graves and believe there could be as many as 20 graves in the area. Metal detectors have picked up signals in multiple spots.

“The burial site lies just beneath the peat. The signals are so strong that we can almost pinpoint where the brooches are,” says Diinhoff.

Metal detector enthusiasts locate the graves

In addition to the three graves at Skumsnes, archaeologists from the University Museum of Bergen have excavated four Viking Age graves at Berstad in Stad municipality.

“In one year, we've excavated more Viking Age graves than we normally do in ten years,” says Diinhoff.

Some of this is coincidental, but much of it is thanks to metal detector enthusiasts.

According to Diinhoff, there should actually be more such excavations.

Viking Age graves are especially easy to find because they contain objects.

“But when people find them on their land, they often remain silent. This happens alarmingly often,” he says.

Many could disappear within 50 years

“ When we’re finally on-site, we often learn that a grave was found years ago but was simply plowed over. We’re losing an immense number of these graves,” says Diinhoff.

He explains that there is a misconception that it is expensive to have such finds investigated, but assures that it costs nothing. The government covers the expenses.

On one hand, it is beneficial if some graves remain untouched, says Diinhoff. In 50 years, better methods will allow us to uncover even more than we can today.

At the same time, many graves will not last another 50 years. They are often shallow and located right on the edge of cultivated land.

“Metal detectors sometimes force us to excavate graves we would have otherwise preserved. But much of what we find with metal detectors will only be recoverable for a few more years before it's destroyed,” he says.

Coins as decoration and currency

The Hedeby coin is an exciting find, confirms archaeologist Unn Pedersen from the University of Oslo.

She is an expert on the Viking Age and has studied jewellery, craftmanship, and decorative objects from the period.

“A silver coin like this on a bead necklace shows that the Viking Age was a time of transition,” she says.

A new form of trade was emerging, but gift exchange still dominated in Scandinavia. As a result, silver from this period is found in many different forms.

“For the woman buried here, it may have had greater value as jewellery. It may have told a story about her identity and the network she was part of,” says Pedersen.

“There’s an ongoing negotiation over the meaning of this silver. In this case, a coin became jewelry and was buried in a grave. But it could just as easily have been cut up and used as payment silver ,” she says.

Typical wealthy women's graves

Another piece of jewellery from the grave was also originally something else. A Carolingian sword belt fitting had been transformed into a trefoil brooch.

“This shows how military equipment from France was repurposed into jewellery in Scandinavia,” says Pedersen.

“Initially, the fittings were reused and modified, as was done here. But eventually, jewellery t inspired by this design began to be produced locally,” she says.

Trefoil brooches became popular among women during the Viking Age. Early designs imitated the plant motifs from the original Carolingian fittings, but over time, animal motifs, more favoured in the Nordic regions, became prevalent.

According to Pedersen, the Skumsnes graves are typical examples of wealthy women’s graves from the Viking Age, characterised by a combination of jewellery and textile tools.

“If not members of the elite, these women were cerftainly high up in the social and economic hierarchy,” she says.

The textile tools and jewellery reflect a female role, but they also point to a reality, the archaeologist notes. Increased trade and demand for sails and textiles provided opportunities for women.

“Through textile work, women could accumulate wealth during the early Viking Age,” she says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Most viewed

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.