Norwegian archaeology find of the year:

The remains of this Viking ship

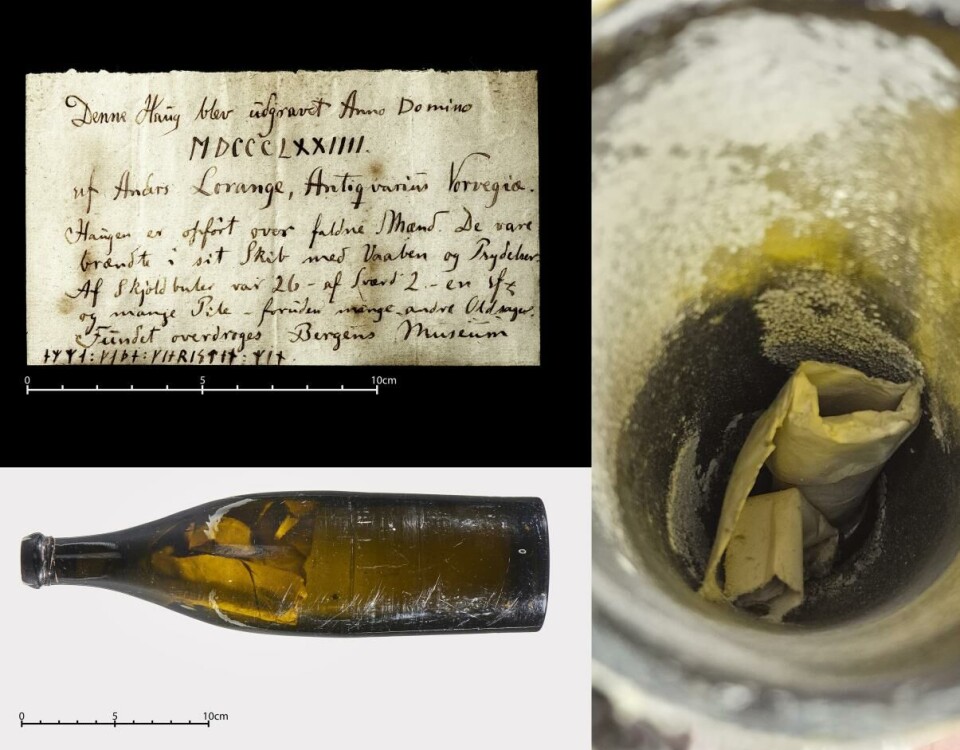

Archaeologists discovered several traces of an enormous Viking ship at the Myklebust burial mound. They also found a message in a bottle from the person who first excavated here, 150 years ago.

The remains of a massive Viking ship still lie in a burial mound in the centre of Nordfjordeid, western Norway.

A chieftain was buried here, 1,200 years ago.

150 years ago, a small part of the mound was excavated by Anders Lorange, the first employed archaeologist at the University of Bergen.

This October, archaeologists from the same university uncovered even more remains of the enormous Viking ship.

And a message in a bottle from Lorange (link in Norwegian).

Voted by Norwegian archaeologists themselves

Although Lorange forgot to record his discovery of a bronze vessel containing remains, he made sure to pay tribute to his beloved – twice.

On Friday, November 15, the discoveries at the Myklebust burial mound were voted the find of the year by Norwegian archaeologists.

The Myklebust burial mound won by a narrow margin. A silver treasure from the Viking Age and the discovery of new rock carvings in Northern Norway also received significant votes.

Second year in a row

"This is the second year in a row that we've won," says Søren Diinhoff, archaeologist and researcher at the University Museum of Bergen.

Last year, a Stone Age grave took the title.

"Of course, one might debate whether a message in a bottle from the 1800s is more significant than silver rings from the Viking Age. But part of our job as archaeologists is to present our findings effectively, and we came well-prepared and delivered,” he says.

Most viewed

Whether the ship in the Myklebust burial mound is the largest found in Norway is not something Diinhoff is focused on. The archaeologist notes that the Viking Age is challenging to portray accurately, as misconceptions arise easily.

“During our media coverage, the ship became the largest in Norway. Then, suddenly, it was the largest in the world,” he says.

For context, the largest Viking ship discovered so far is a 36-metre-long vessel from Roskilde, Denmark.

Still, there is no doubt that the Myklebust Ship was large. Upcoming analyses will provide more clarity on its approximate size.

"We'll be able to determine whether the ship was burned at the burial site or not. And if we can identify the type of wood it was made from, we might even find out whether it was around 30 metres long," says Diinhoff.

Old discoveries, new methods

Ingar Mørkestøl Gundersen is head of the Norwegian Archaeology Meeting, which recently held its annual gathering in Oslo. The conference is the ‘major event of the year for Archaeology-Norway,’ according to its own website, and has been held since 1927.

He believes there are two key reasons why the Myklebust burial mound was voted the top find.

“First, it demonstrates the potential of revisiting well-known and previously excavated cultural heritage sites,” says Gundersen.

Thanks to modern methods and advancements in knowledge, archaeologists can uncover entirely new insights today compared to when the Myklebust burial mound was first excavated in 1874.

"Additionally, this discovery brings us remarkably close to our field’s history. Lorange’s bottle message offers a rare and intriguing glimpse into the life of one of Norwegian archaeology’s pioneers. Naturally, this has sparked significant interest," he says.

Fewer excavations, fewer finds

The 240 archaeologists could vote on seven different discoveries. According to Gundersen, fewer standout finds were reported this year compared to last, and fewer discoveries were submitted to the conference overall.

“This may reflect a downturn in field activity this year,” he speculates.

Gundersen does not have data to confirm whether there were fewer excavations this year than in previous years.

"But the era of large infrastructure projects has passed. As a result, there are fewer multi-year projects compared to what we were accustomed to in the early 2000s. The development pressure in the Old Town and the old harbour area in Oslo is also easing. Many archaeologists have worked there over the past 20 years, but now they're facing uncertain times," he says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.