Researchers have uncovered an ancient mountain shack used by Viking Age travellers in Norway

The most surprising discovery is how much of a mess they made with their food inside the shack, says an archaeologist.

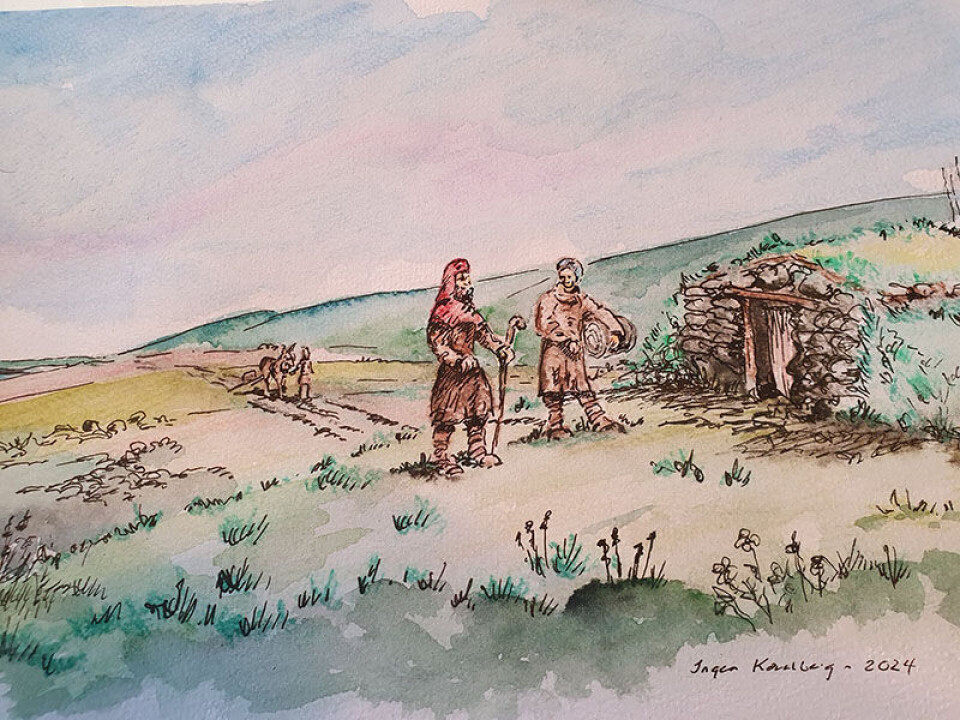

The shack was built of stone and turf.

There were likely wide benches along the walls where people could sit or sleep.

While it did not offer much luxury, it provided much-needed shelter from the wind and weather. Similar shacks were built at regular intervals along Store Nordmannslepa, one of the main routes across the Hardanger Plateau in those times.

In the middle of the shack was a large hearth, where travellers could cook their food.

Kilograms of food waste

“We’ve found kilograms of old food remains that were tossed into the fire,” says archaeologist Marianne Vedeler.

Normally, during this period – spanning the Viking Age and the Middle Ages – people would carefully take their trash outside and dispose of it in a waste pit.

“They couldn't be bothered to do that here. They just sat inside, made a mess, and threw everything into the fire,” she says.

Over time, this food waste built up into a 40-centimetre-thick layer of soot and animal bones inside the hearth.

“It’s packed with animal bones – reindeer, sheep, birds, fish, and other things they’ve eaten,” she says.

A desolate stone shack

Vedeler, an archaeologist at the Museum of Cultural History, is involved in a research project focusing on food in the Middle Ages. While the focus has been on urban areas, the team also wanted to explore rural food culture and places where people spent the night.

The shack on the Hardanger Plateau was known to archaeologists thanks to a travel journal from 1821. In it, scientist Christoffer Hansteen wrote about finding ‘a desolate stone shack whose roof had collapsed’ while hiking along Store Nordmannsslepa.

“Some archaeologists also visited in the 1980s and found animal bones,” says Vedeler.

They had also taken a charcoal sample but never analysed it.

Vedeler and her team took over and found that the charcoal dated back to the 12th century.

An adventure unfolds

“We were a group of five enthusiastic archaeologists who decided to head up there and dig,” says Vedeler.

What followed was an adventure, as finding the shack was not easy.

The shack was not where it was marked on the map.

“It was a bit like extreme sports. We wandered around the terrain for a while before we found it, and then had to haul shovels, picks, and equipment several kilometres into the mountains,” says the archaeologist.

Eventually, they located the shack Hansteen had described, as well as an even older one, which they decided to excavate.

It soon became clear that the old shack had been used during the Viking Age and the Middle Ages.

A lighter from the Viking Age

Just inside what was once the doorway, the archaeologists found two finely-crafted arrowheads from the Viking Age.

‘This must be evidence of a hunter who was active there during the Viking Age. Iron was valuable, and a lot of effort went into forging these arrowheads,’ the Museum of Cultural History wrote in an article about the excavation (link in Norwegian).

The team also discovered a fire striker.

“It's a kind of old-fashioned lighter used to start fires,” explains Vedeler.

Fire strikers were used during the Viking Age and the Middle Ages, along with flint – which was also found in the shack. By striking the fire striker against something flammable, sparks would fly and ignite the material.

The fire striker the archaeologists found was of the type used in the Viking Age.

Outside the shack, there were more signs of past travellers.

With the help of a metal detector, the archaeologists uncovered numerous old horseshoes and horseshoe nails.

“They clearly parked their horses here before going inside,” she says.

A challenging journey

“It’s fascinating to see how people adapted to the harsh conditions of the mountains when travelling. How they managed food and overnight stays,” says Vedeler.

“I think the reason they were so messy is that no one lived here permanently; people just used it for shelter and to spend the night,” she adds.

Some travellers crossed the mountains to hunt reindeer, while others were merchants.

“The Hardanger Plateau was a tough place to transport goods, but it was a major route for trade, with goods travelling from west to east and vice versa. People transported animals and goods for sale,” she says.

But the weather in the mountains was often bad, and there weren't many such shacks along the route.

“That’s probably why there were strict rules for using these shacks,” says the archaeologist.

Plans for more excavation

Vedeler and her colleagues have collected samples from the hearth, taken from the bottom, middle, and top layers.

These samples will reveal how long the shack was in use.

If more funding becomes available, the team plans to return next year to continue excavation.

“We didn't finish excavating the entire hearth or uncovering enough to get a full picture of what the shack looked like. We can see the rooms and the stone walls, but to understand it better, we need to dig a bit more,” says Vedeler.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no