A 1,300-year-old arrow and horse dung have emerged from a melting Norwegian glacier

“It’s a type of arrow that is very, very rare,” researcher says.

“There are some incredible finds on the ice

and land, in areas we’ve never been able to explore before because they were

covered in ice,” says Espen Finstad.

The experienced glacial archaeologist had time for a quick chat before heading back to the Lendbreen ice patch for the day’s work. He is one of the leaders of the Secrets of the Ice preservation project.

“We’ve spotted several items we plan to investigate further today, including textiles and leather still encased in the ice,” he says.

Seven archaeologists, accompanied by pack horses, hiked up to the ice patch known as Lendbreen in Jotunheimen. The fieldwork was completed on 1 September, and they have made several significant discoveries.

“We’ve made some fantastic arrow finds,” says Finstad.

A small textile fragment

For over a thousand years, people have travelled over this mountain pass, dating back to the Viking Age and the Middle Ages. Glacial archaeologists have previously described this forgotten mountain pass as one of their most unbelievable discoveries. It was here they uncovered Norway's oldest piece of clothing, a 1,700-year-old tunic, which melted out of the ice in 2011.

Day one at the ice patch was marked by wind and rain, with much of the time spent inside tents. However, a brief break in the weather in the evening allowed them to make their first find: a well-preserved textile fragment.

“We’ve found many textile fragments here over the years, so it’s not particularly unusual,” says Finstad. “We have hundreds of these textile fragments and have found everything from a Viking-era mitten to a tunic. But it's fun to see that things are still emerging.”

The first arrow of the year

Last week the team found the first arrow of the year.

‘BOOM! First arrow of the year, found on the ice at Lendbreen,’ they announced on their popular Facebook page.

The arrow is estimated to be 1,300 years old, based on the shape of the arrowhead.

‘When finds melt out on the ice surface, this normally signifies that they have not been out of the ice, since they were lost so long ago. The objects are frozen in time. As a result, the preservation is just stunning,’ the archaeologists wrote enthusiastically.

The iron arrowhead, sinew at the joint, and wooden shaft are all intact. The only thing missing is the fletching, though a faint imprint remains.

And a very rare arrow

Then the archaeologists found an even more special arrow.

“It's the type with three blades,” says Finstad. “It’s a type of arrow that is very, very rare.”

This is the second time the glacial archaeologists have found this type of three-bladed arrowhead. The previous one was from the Viking Age, which you can read more about it in the article – The last person who touched this three-bladed arrowhead was a Viking.

This year's arrow is older, the archaeologists wrote on Facebook. Its design suggests it dates back to the early Iron Age, around AD 300-600.

‘This discovery will be a goldmine of information about ancient archery techniques when we get it back to the lab!’ they wrote.

Horse remains found

Archaeologists also uncovered a large horse canine.

‘It likely belonged to one of the many packhorses that traversed the Lendbreen pass during the Iron Age and Medieval period,’ they wrote on Facebook.

They also found plenty of horse dung.

One follower asked if they planned to examine the horse dung.

The Secrets archaeologists responded that they have tried this before, but bacteria had degraded the DNA, leaving no results. However, they noted it could still be interesting to look at the plant content within the dung.

On the other hand, they have successfully found DNA in the teeth and bones of horses from previous discoveries at Lendbreen. The results from these analyses have not yet been published.

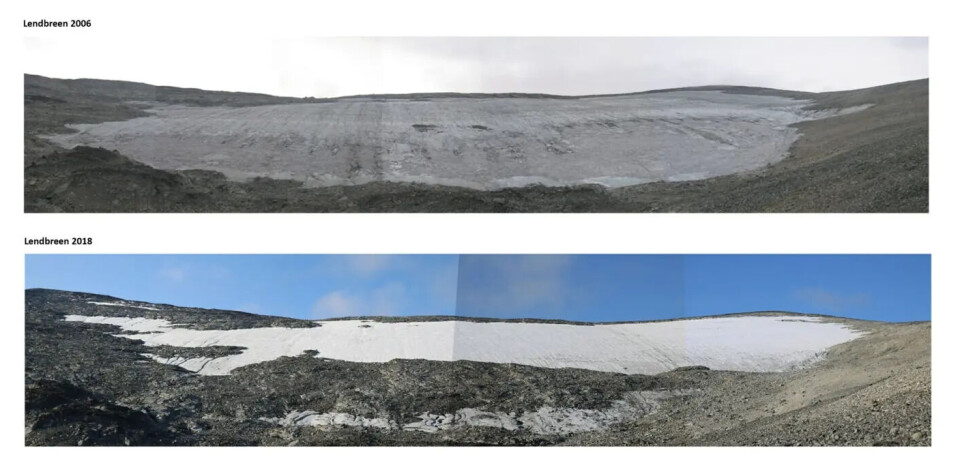

A changing climate

The archaeologists also visited Lendbreen last year, but there was more snow then. This year, significant snowmelt has occurred.

‘First glimpse of Lendbreen, and oh dear, it has taken quite a hit!’ the Secrets archaeologists wrote earlier last week.

This is the dark side of glacial archaeology, they commented. And at the same time – "the ice is melting, and we have to make the best of it."

“Which part of the glacier is most affected varies from year to year, depending on how the snow settles over the winter,” Finstad explains on the phone from the mountains.

Some followers on Facebook questioned whether the climate hasn’t always been changing.

‘In the larger picture, we have had a remarkably stable climate for many thousands of years. This is now changing due to human activities, and the melting of mountain ice is a very concrete example of what is going on,’ the archaeologists reply.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no