The plan was to renovate a laundry room. But then bones from a 12 000 year old polar bear showed up

This is the story of how the best-preserved Ice Age polar bear in the world ended up at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger in the 1980s. Norway's first Stone Age people may have lived alongside this polar bear.

It was in 1976 that the married couple Reidun and Sverre Asheim were to expand the basement laundry room in their house on the island Finnøy outside Stavanger in southwestern Norway.

When they dug up the basement floor, they came across some bone remains. They put the remains in a margarine crate and stored it away, before pouring a new basement floor.

The crate was left untouched for several years and then given to a friend of the family.

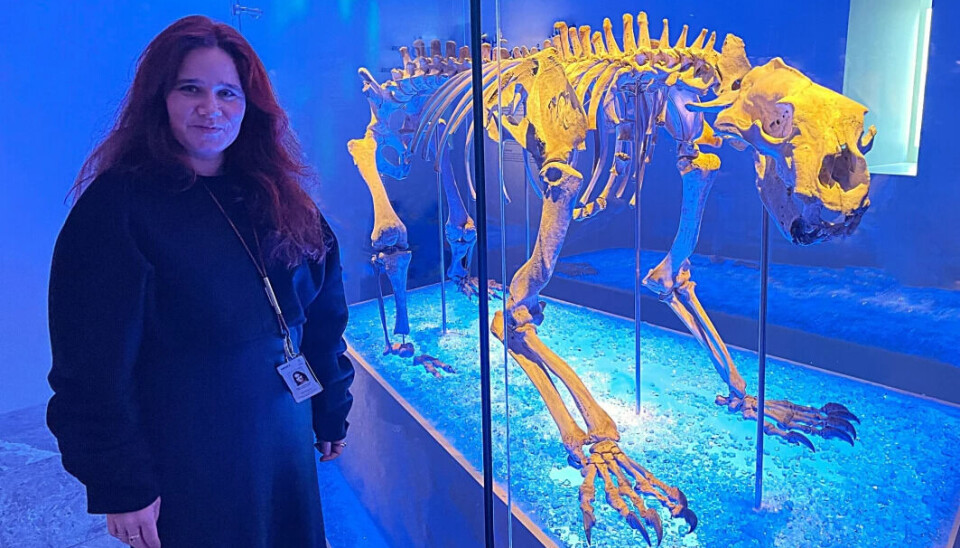

“The son of this friend was watching a Stone Age excavation one day and got into a conversation with the geologist Hanne Thomsen at the Museum of Archaeology,” archaeologist Kristin Armstrong Oma at the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger tells sciencenorway.no.

“The geologist became curious and asked the boy if she could see the crate with the bone remains,” Oma says.

Among the bones in the crate, a particularly large humerus bone caught Thomsen's attention.

What kind of animal was this?

The researchers excavate the basement

Zoological analysis quickly revealed that it was a polar bear.

Then, in 1982 - six years after the initial discovery - researchers Hanne Thomsen, Asbjørn Simonsen and Per Blystad from the Museum of Archaeology in Stavanger, together with Rolf Lie from the Zoological Museum in Bergen, were given permission to dig up the floor in the Asheim couple's new laundry room.

It was the most fun thing they have done in their research career.

Because they made a unique discovery:

In a layer of clay a little further down into the ground, there were more bone remains. Together with the bones in the dairy case, the researchers now had an almost complete polar bear skeleton from the end of the Ice Age.

From a place where there have hardly been polar bears in the last 12,000 years.

Nothing like it had ever been found.

“When we found the polar bear, there were only nine other discoveries of polar bears from the Ice Age in the entire world. And this is still the most complete Ice Age polar bear from so far back in time,” Hanne Thomsen told the University of Stavanger’s website.

When the great glacier melted

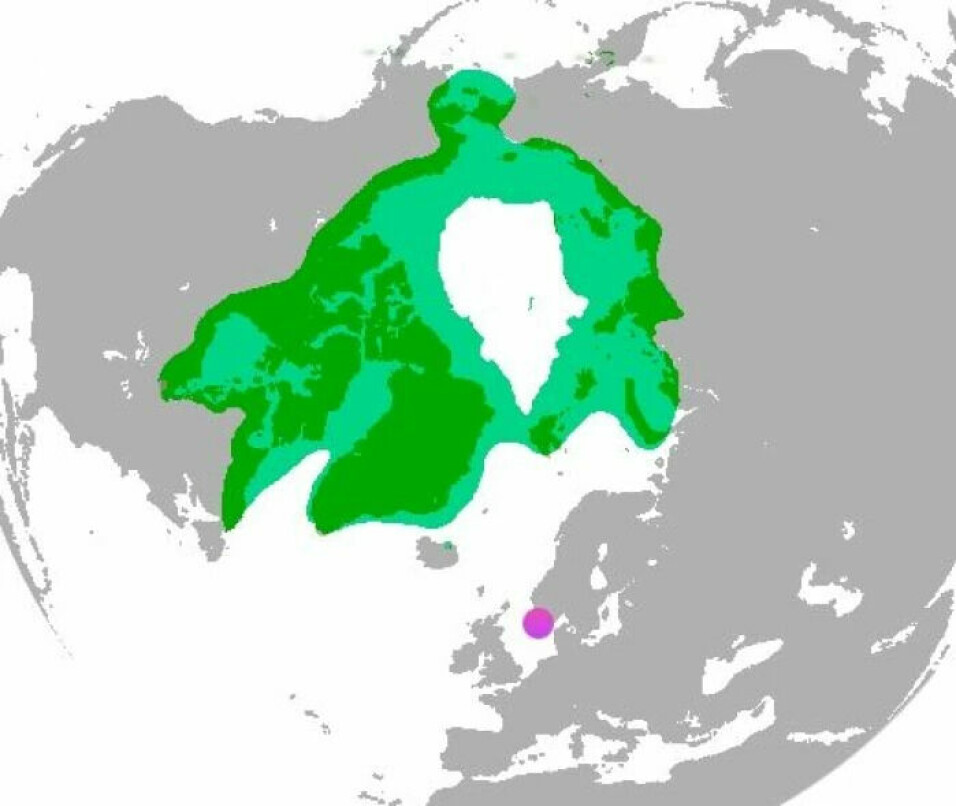

When the huge ice sheet over northern Europe melted well over 12,000 years ago, the edge of the great glacier lay across Scandinavia and southern Norway for a while.

The first people who followed the edge of the glacier to the north may have reached the area surrounding Stavanger around this time.

Maybe they met the polar bear.

The male bear weighs almost 600 kilos. The teeth reveal that the animal died at the age of 28.

The skeleton from Finnøy is currently the best-preserved Ice Age polar bear in the world.

The clay’s optimal preserving conditions meant that the researchers also found parts of the bear’s stomach. In it were the remains of a seal. Was it the same type of seal that Norway's first Stone Age people hunted?

A charred piece of dwarf birch was also found alongside the polar bear.

The researchers believe it is unlikely that the low tundra vegetation in the area began to burn completely by itself 12,000 years ago.

Did the Stone Age people light a fire?

Died at sea

The polar bear that the museum in Stavanger has named Finn, died out at sea. Probably due to old age.

About 12,400 years ago, the polar bear sank a few tens of metres to the seabed. There it was quickly buried under clay.

When the enormous pressure from the ice masses had been gone for a while, Finnøy rose out of the sea together with much other Norwegian coastal scenery. Today, the house with the basement laundry room where Finn was found is well up on dry land.

A hybrid

“Now we also know that this polar bear is a hybrid,” Oma says.

Scientists have found genetic material from brown bears in the polar bear's DNA.

It tells us that polar bears and brown bears have produced offspring together in a warmer climate.

“Our polar bear lived in a time when the climate was rapidly warming. Perhaps the polar bears that lived here over 12,000 years ago mated with brown bears as a survival strategy,” she says.

Polar bears are descended from brown bears.

But scientists have, for a long time, been unsure about how long ago the two animal species separated. Perhaps it was as long as 4-5 million years ago. Maybe it was a good deal later.

Lions and tigers can also produce offspring together. So can horses and donkeys.

But unlike these animals, a polar bear and a brown bear can produce cubs that can go on to mate and have cubs of their own.

They are not sterile.

The very fact that polar bears and brown bears can mate and produce cubs that themselves can also become parents makes it difficult for researchers to determine when they became two different species. The two species may have mixed up to several times.

Completely different teeth

The teeth are perhaps the most different thing between polar bears and brown bears.

“In the Finnøy polar bear, we see changes in the skeleton that we do not normally find in polar bears. It has teeth that are more primitive and look more like brown bear teeth than modern day’s polar bear teeth do,” Oma says.

Polar bears have molars with sharp and straight edges, designed for a diet that consists exclusively of meat.

“The brown bear has much more rounded teeth. This is because it is omnivorous and has a diet that often consists of a lot of berries,” she says.

Oma and her colleagues in Stavanger can see traces of both bear species in the animal they have exhibited. Although it is mostly a polar bear that stands in the museum.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

------