Remains of what may be a temple where Norse gods were worshiped have been found in Norway

Researchers believe they have found the remains of a pagan temple, where Vikings made sacrifices to gods like Thor and Odin. If so, then this would be the first Norse temple identified in Norway.

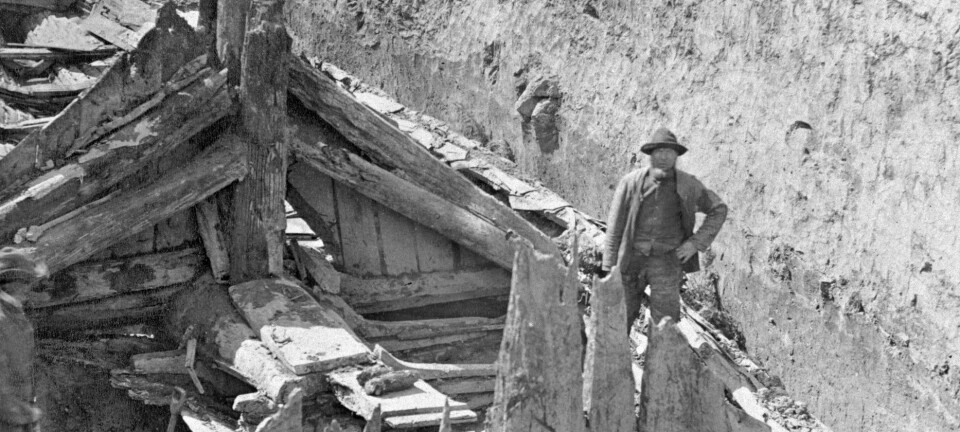

The find was uncovered during an excavation of the Ose farm in Ørsta, in Møre og Romsdal County. The regional bureau of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK, was first to report on the find.

Researchers found evidence that people have been calling the location home for a long time, perhaps as far back as the 6th century.

But it’s not the remains of houses and longhouses that got people’s attention.

Instead, it was evidence on the ground of a large structure, as long as fourteen metres and eight metres wide, with evidence of thick walls and smoky rituals.

The researchers believe this was a so-called god's temple or pagan temple. A place where people made sacrifices to Odin and his extended family, before Christianity came to Norway.

Very rare

“This is the first of its kind in Norway,” Søren Diinhoff said to sciencenorway.no.

Diinhoff is a researcher at the University of Bergen who is in charge of the dig.

The researchers started their excavation because new homes were going to be built in the field, but Diinhoff says that he and his colleagues had suspicions that they would find something even before they put a shovel in the ground.

“The northern part of the area already contains a historic yard for the Ose farm, so we knew there was a high likelihood of at least finding a medieval settlement,” he said.

And it is precisely in the northern part of the field that researchers have now uncovered evidence of several buildings. The team has not yet sent pieces of charcoal for dating, but the settlement probably dates back to the 6th century AD.

“It has been difficult to find this settlement for many years,” Diinhoff said.

He says this is probably because Viking-era buildings were located inside and under the current farm yard.

“Unfortunately, it’s not that often that archaeologists have the opportunity to dig in places like this. Being able to excavate Ose is of great value,” he said.

Viking religious life

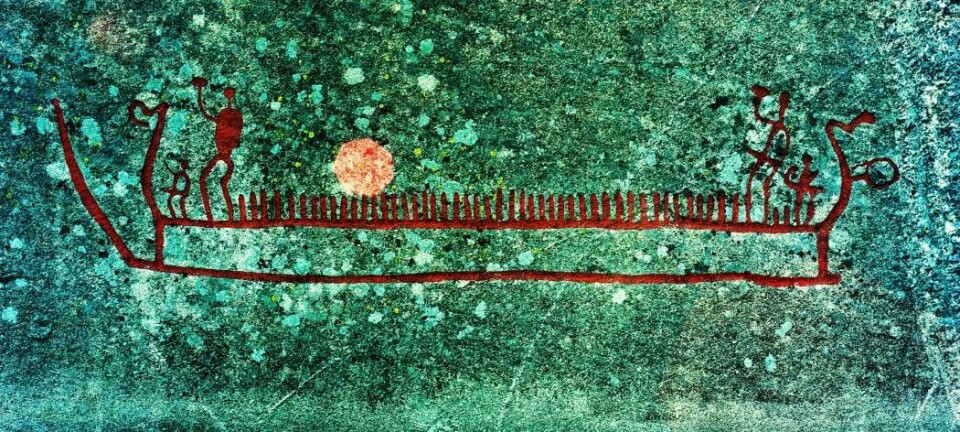

Several sources provide an insight into the northerners' religious life during the Iron Age, including traces of burial customs and rituals, sacrificial sites in the landscape, and buildings that show evidence of cults or worship.

Other researchers have previously presented what they believe are similar findings. Diinhoff says it’s not that simple.

“Just because you have found a fireplace and a gold bracteate (a type of gold jewellery) it doesn’t mean you have found what we found. A spade may be a spade, but not everything is a house for the worship of the gods,” he said.

Some of the finds that provide evidence of the northerners' spiritual life are pits — cooking pits. Large clusters of cooking pits were common during the middle of the Iron Age in the areas between farms.

Diinhoff himself believes that these places, with their raised terraces and water views, are what are called "horg" in old texts. Researchers have found these kinds of places in Hardanger, for example.

“These were a ritual sacrificial site where consecrated meals were prepared for religious celebrations,” he said.

Read more about one such possible sacrificial site in this article, produced and financed by NTNU: More than 1000 cooking pits of yore found in one area. Was this a ritual gathering place?

Upheavals

Researchers have found evidence of major societal changes throughout the Roman Iron Age.

Contact with the aging Roman Empire and Germanic tribes in the south increased, and the farms with the best soil expanded considerably — some were up to seven times larger than they were before.

An elite of rich peasant families held power, farmers with large landholdings left behind rich graves, imported goods and large farms.

“It was expected that the families on the large farms would seize power and control in society. The big farmer (chief) was now the lawgiver, warlord and leader of the cult,” says Diinhoff.

During this period, the cooking pit fields and parties moved indoors — into large halls, under the chief's control.

“We see this in Ose. We have what is probably a large longhouse from the middle of the Iron Age, and we have a cooking pit field. We also have a strange circular enclosure with a small hut in it in the southern part of the longhouse,” he said.

“This find has quite a few parallels in southern Scandinavia, where it is also considered to be evidence of worship,” says Diinhoff, who added that a ritual penis-shaped stone had been found at Ose earlier.

Large temple

“All in all, it’s clear there was a large farm established at Ose sometime towards the end of the older Iron Age, and this farm has had a central function in the cult in the area,” Diinhoff said.

“Then, later in the younger Iron Age, we have the distinctive building that we see as a place of worship,” he said.

This is where the big house of the gods comes in.

It was fourteen metres in length, and seven metres in width. The walls were strong, and four posts in the centre of the building supported an elevated central section. In short, a significant building.

“There are really no other parallels than a handful of buildings from southern Scandinavia that are this kind of place of worship. They have been found in a few very large settlements, such as Uppåkra (in Skåne, in southern Sweden) and Tissø (in Sjælland in Denmark).

“These structures appear at a time when we have the first indications of the worship of Odin, and thus the Nordic gods. And since this is a house of worship that belonged to the elite of society, there is little doubt that this is the foremost house of worship in the Norse religion,” he said.

"Osehuset" is a clear parallel to the southern Scandinavian structures, the researcher said.

“It has the same size, the same appearance. It is surrounded by thick, charcoal-containing layers of coke, and had it not been for the acidic soil, then surely many animal bones,” he said.

Danish archaeologist not quite convinced

Søren Sindbæk, professor of archaeology at Aarhus University in Denmark, says that the newly discovered building is reminiscent of a house of the gods like the one found in Skåne.

“At Uppåkrå and other areas that have been said to be places of worship and houses of the gods, a number of objects and sacrificial offerings have also been found that support the theory. But I don’t see that they have found these things in Ørsta,” Sindbæk said to the website videnskab.dk.

“The most common feature of localities we have recognized as pre-Christian cult buildings is the discovery of destroyed weapons, which appear to have been part of the cult. We have seen this both at Tissø and Uppåkrå,” he said.

“So if they had found three or four curved spearheads in Ørsta, I would have been very excited about the find. But without having found those kinds of objects, it is difficult to be convinced that it is a place of worship,” Sindbæk said.

However, the archaeologists have found the same kinds of gold objects that have been found in Sweden and Denmark. Diinhoff believes this is due to the fact that Osehuset dates to the Viking Age, while the other gold finds have been made in temples from the age of migration.

“Had the floor layer in our house been preserved, we would probably also have found objects offered in sacrifice,” Diinhoff says.

Unique?

The findings are described by the University of Bergen as “unique”; but Diinhoff is more modest. When asked if this is a fantastic find, he answers:

“Not really. At least it shouldn’t be. The fact is, however, that it is the first of its kind in Norway,” he said.

He points out that there has been discussion about similar finds having been made in Norway, but says that he doesn’t think that is the case, even though he says that some colleagues have been close.

“For example, when gold foil figures (small thin pieces of beaten gold that have been stamped with a motif) have been found under medieval churches, it is probably a house of worship like this that was once there. But the buildings themselves have not been found until now,” he said. “So yes, the find is rare.”

Read more about gold foil figures in this article: The mystery from pre-Viking days: Only the most powerful had these little pieces of gold

When the Norse religion disappeared, and Christianity came to the elites, these places of worship perhaps disappeared under the churches, and were thus wiped out.

“It is also a strange coincidence that we also find cooking pit fields near the early churches. The connection is that these were the place where people worshipped for a long time,” says Diinhoff.

“First as a cooking pit field (horg), then a house of the gods (hov), and finally a church. At Ose, the house of the gods was preserved because the first church was not built here, but on one of the neighbouring farms,” he said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———