Researchers have examined the burial mound where the Gokstad Viking ship was found. What they found surprised them.

“The first thing that struck me was that it was so neat. All the layers were so clean,” says archaeologist Rebecca Cannell to sciencenorway.no.

The Gokstad ship is one of the most famous Viking ships in the world. It lay almost completely in peace inside a burial mound in Vestfold for up to a thousand years. The ship was laid to rest around the year 900 AD.

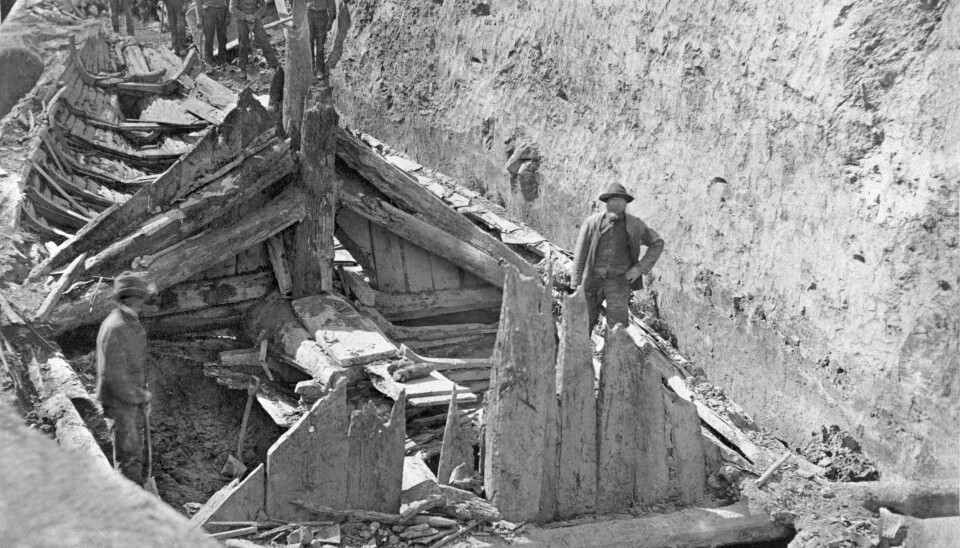

In 1880, the grave was opened, and archaeologists found, among other things, several smaller boats and remains of several animal victims — in addition to the 24-meter-long, very well-preserved Viking ship.

But the burial mound itself — Gokstadhaugen — has received little attention compared to the spectacular objects that were taken out at the time, as reported in a new article in the magazine Antiquity.

A Norwegian research group has tried to find out whether the huge burial mound can tell something about how the burial was secured, or reveal something about those who built the mound. The researchers also want to know more about how the burial mound fits into the surrounding landscape.

A landmark

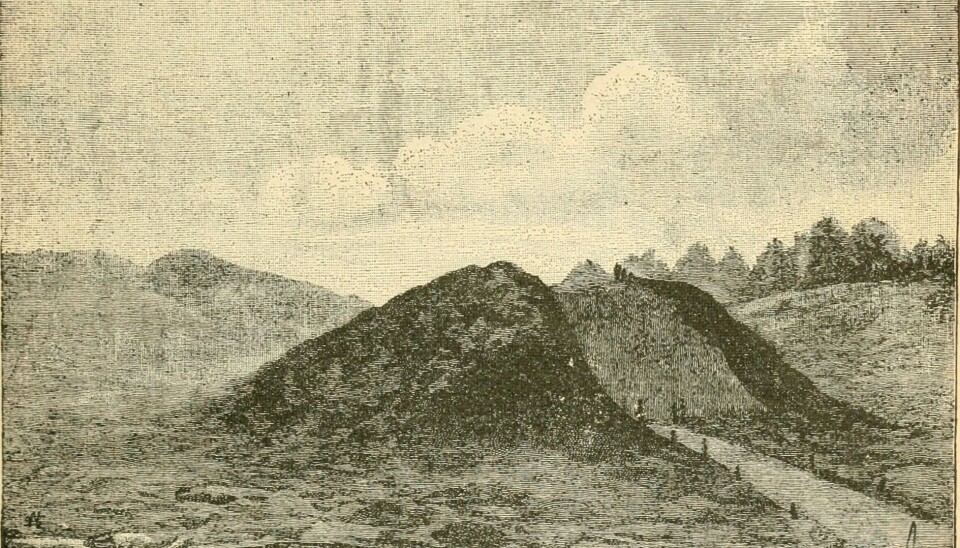

Archaeologists know that the burial mounds themselves were very important. They were located in a manner that ensured they were easy to see, and the Gokstad mound was located near Heimdalsjordet — a trading place about half a kilometre away.

“The mounds were often placed by Viking Age roads, which is also the case with Gokstadhaugen,” Rebecca Cannell said to sciencenorway.no. She is an archaeologist and soil researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), and has been involved in the new study on the burial mound.

“The mounds were meant to be seen up close and be a part of people's everyday lives,” she said.

At the same time, the mound could be seen from around 20 other burial mounds nearby, while at the same time it was close to another, as yet undated burial mound, according to the Antiquity article.

And Gokstadhaugen is still a presence in the Vestfold landscape. Much of the mound is still there, although some was excavated to remove the contents of the grave 140 years ago.

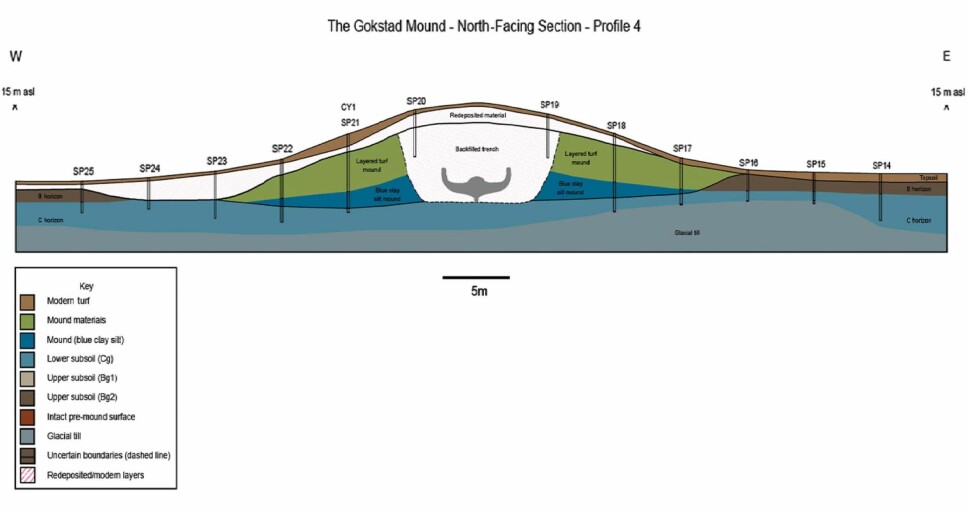

The researchers have taken a number of core samples to find out how the mound was constructed, and what it was made of. They also used georadar to see what was inside the burial mound. Combined with magnetometers, these technologies can create an image of what is under the ground — without excavation. The researchers also examined a large area around the grave using these tools.

Cannell says the investigations revealed something completely different than they expected beforehand.

A pool?

“We expected to find a trench in which the ship was placed,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

But it turned out that the construction of the grave was much more comprehensive than this.

The Gokstad mound is huge compared to many other burial mounds. Today it measures 48 by 43 metres, but the mound was not constructed simply by placing earth and stone over the ship and the burial chamber.

Cannell says they found traces of a large trench. This comprised an area that was almost as large as the surface under which the mound was excavated, where the upper part of the soil’s surface was removed.

“I have worked with the soil in this area for a long time, and it’s not easy digging,” she said.

The soil here consists of moist blue clay, among other things.

“It’s sticky and heavy, and it must have been a lot of work,” she said.

The deep trench was filled with muddy water and blue clay before the mound was closed in, so the ship could have been in a kind of shallow basin or pool, according to the investigations by Cannell and her colleagues.

She also argues that this was probably deliberate, since the workers would have known about the result of digging such a deep and large pit.

The researchers have also discussed whether there was an elevated, dry area where a walkway went over to the ship, which may have been used to put the grave goods on board before the grave was closed.

Layer upon layer

The samples and investigations from the mound should also reveal what kind of layers was laid to build up the Gokstad mound. Once again, the undisturbed parts of the mound held a surprise.

“The first thing that struck me was how orderly it was. It has been there for a thousand years, and all the layers were very clear,” she said.

The layers were thus clearly separated and must have been layered in a certain way on purpose. This probably means that those who constructed the mound were precise in their work, and that there was a clear plan behind it, the researchers say.

Among the materials the builders used were birch bark and moss, which were used to cover the burial chamber of the ship. The ship itself was buried in blue clay, and the clay came up at least to the ship’s waterline.

This clay was very dense and ensured that the grave was buried in a moist, airtight environment — which is ideal for preserving wood. This also helps explain why the contents of the grave were so well preserved.

Researchers have speculated whether the blue clay was used because the builders knew that it would preserve the ship into the future, but it’s nearly impossible to determine the motivation behind its use.

Peat and soil from the excavation were used to cover the burial mound when it was closed up.

The various materials, including the blue clay, all have clear colours, and the researchers interpret this choice of materials as a link to the local landscape.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Reference:

Cannell, Bill, Macphail: Constructing and deconstructing the Gokstad mound. Antiquity, 2020. DOI: 10.15184 / aqy.2020.162. Summary

———