New video footage shows what could be the oldest known shipwreck at the bottom of Norway's largest lake

The researchers managed to catch a glimpse of the wreck before the underwater robot ran out of power.

Last November, researchers from the Norwegian Defense Research Institute and The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) discovered an old shipwreck at the bottom of Norway's largest lake, Mjøsa. The find drew attention both nationally and internationally.

The ship is likely from between 1300 and 1850, but could be even older.

The ship could potentially be the oldest ship found in Mjøsa, Gro Kvanli Dæhlin, vice rector at NTNU in Gjøvik, told NRK last year (link in Norwegian).

The wreck was discovered using the underwater robot Hugin. This happened in connection with a mapping of ammunition dumped on the bottom of lake Mjøsa.

Now, for the first time, we can see a glimpse of the wreck on video. It is still not possible to determine how old the ship is, but the images provide new information.

(See the video a little further down in the article.)

Filmed several wrecks

The video was presented at Ocean Week at NTNU in Gjøvik on Thursday morning.

Øyvind Ødegård, researcher at the NTNU University Museum, said that marine archaeologists from several institutions had a gathering at lake Mjøsa during the last week of March.

The researchers dived and used underwater vehicles to study five known wrecks in the lake.

Among them, it was possible to take a closer look at the wreck found in November, called the Storfjord wreck.

Unlike the others, this one is in deep water. The ship is located 400 metres below the surface in the middle of Mjøsa.

It was therefore not possible to dive down. But the researchers sent down a remote-controlled underwater vehicle, an ROV.

“Frantic searching”

They were lucky with the weather. It was necessary for the boat to be completely still while they lowered the ROV into the depths.

Still, it was a close call for the researchers to see what they came for.

When the ROV had reached the bottom, there was six per cent left on the battery. It took half an hour to lower the vehicle, while the engine had to work.

“So when we got down there, there was frantic searching on the seabed. We just managed to catch a few seconds of the wreck,” Øyvind Ødegård said.

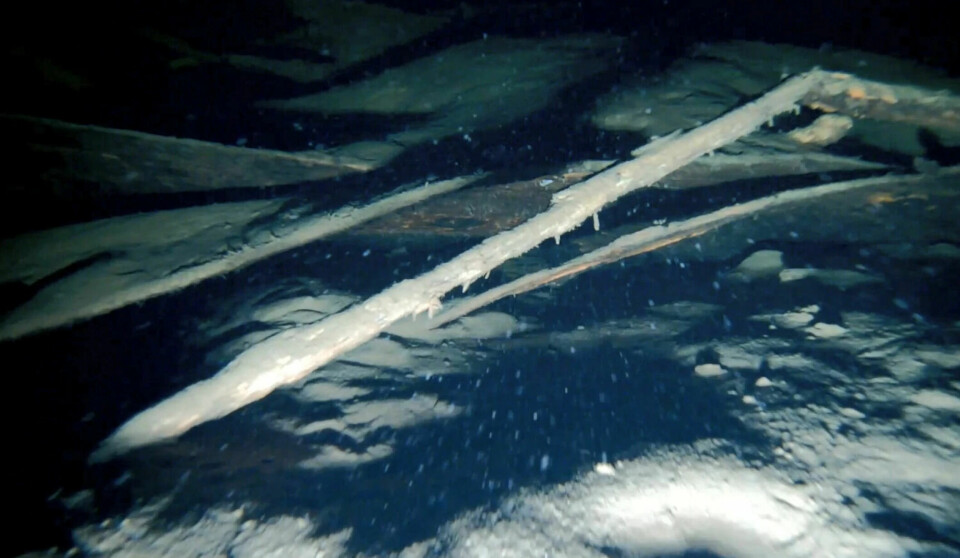

In the video, we see bare seabed, a cloud of sand, and then some of the wreck comes into view:

What the researchers know so far

It was a relief not to see any outboard motors, Ødegård joked.

“There is nothing to rule out that this is really old,” he said.

Ødegård related what they know about the ship so far, and what new information the video provides.

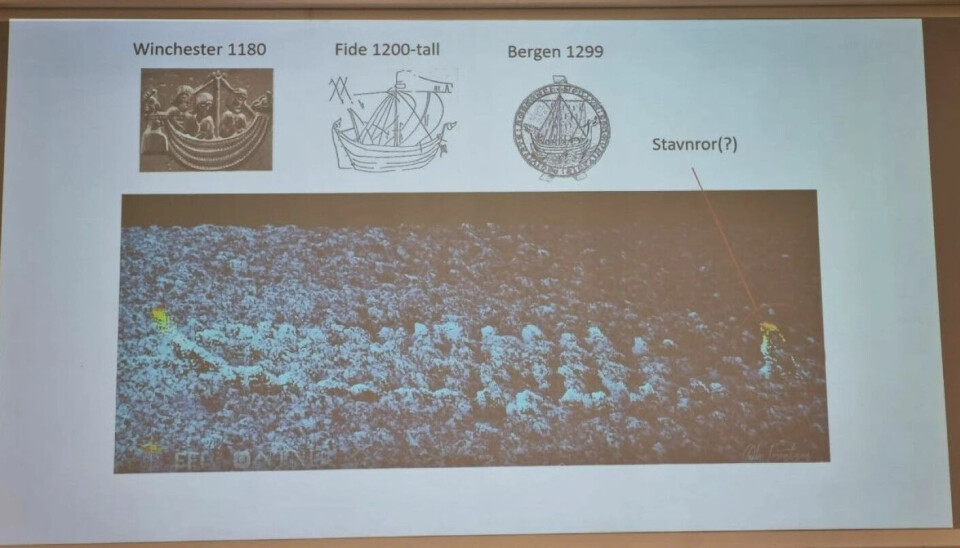

Last year, Hugin took two sonar images with slightly different angles.

“We made some interpretations based on what we saw in the high-resolution sonar images. Among other things, by superimposing the two images, we can say that it is a clinker-built vessel,” he said.

A clinker-built boat is made of wood. One of the characteristics is that the planks of the boat overlap. The construction method is typical Nordic and stretched from the Iron Age until the 20th century, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian).

“Remarkably similar to a Viking ship”

Furthermore, the researchers could see that some of the planks had started to loosen, indicating that the ship had been there for a while.

“If we start with the sonar image that shows the outline of the wreck, it actually looks remarkably like the classic Viking ship or slightly larger Viking boats,” Ødegård said.

The ship is 10 metres long and 2.5 metres wide.

The researchers have also created a 3D model based on the sonar images. Something else caught Ødegård's attention: The protrusions at the ends of the ship, known as stems.

One is more upright and possibly a steering oar, but this is uncertain.

This was not common in Norway before the 14th century. Therefore, the researchers speculated that the ship was built sometime between the 1300s and 1850.

Long and narrow

Ødegård explained to sciencenorway.no that a steering oar is a rudder with hinges at the end of a boat, as on a modern boat.

“While on Viking ships, you had a side rudder. That is why it is called starboard on the right side,” he said.

The side rudder was like an oar with an angle that a crew member would sit and steer with.

However, the oldest archaeological example of a boat with a steering oar that the researchers can compare with looks completely different from the Storfjord wreck.

A long, narrow ship that may have a steering oar could be of interest far beyond regional maritime history, Ødegård said.

No rowlocks

Unfortunately, the video does not show the rudder. The ship keeps its secrets for a while longer.

What we can see in the video is presumably the upper strake.

“On top, you have a slightly stronger, slightly rounded strake that reinforces and prevents it from breaking when you enter or exit the boat, or row,” Ødegård tells sciencenorway.no.

There is no sign of rowlocks on this strake. If the wreck was once a rowing ship, there should have been. Therefore, the video suggests that this may have been a self-propelled vessel, Ødegård said.

The wreck is in the process of disintegrating, but Ødegård believes they still have a fairly intact wreck.

Furthermore, the researchers could see that the boards that had come loose were also broken.

There is no sign that anything has crashed in the wreck, so the boards have broken under their own weight. This suggests that the ship has been there for quite some time, Ødegård said during the presentation.

Want to map the entire seabed

Nevertheless, the researchers still cannot say if the ship is really old, other than that it is definitely not modern.

“But it is permissible to be a little optimistic that this is of great cultural and historical interest,” he said.

Ødegård hopes to be able to examine the ship again, next time with more charge left on the battery.

Most wrecks in lake Mjøsa have been found along the edges, where it is shallow enough for divers to discover wrecks or see them under the ice. The researchers believe there is great potential for finding more wrecks in deeper water.

This is part of the goal of the research programme Oppdrag Mjøsa (Mission Mjøsa). Investigations of the Stordfjord wreck are also a part of this.

The programme’s goals include creating a complete model of the terrain in Mjøsa, mapping cultural heritage sites, identifying hazardous objects that have been dumped, and developing methods for managing lakes, according to Innlandet county municipality (link in Norwegian).

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no