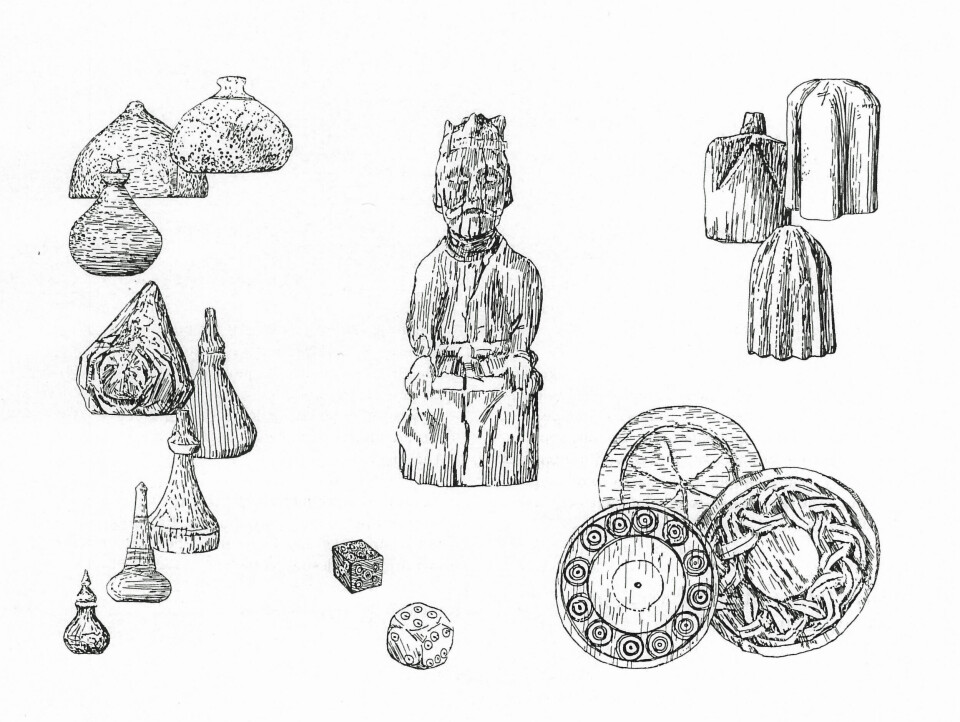

Gaming-pieces and a gaming board found in the Medieval Park in Oslo

New finds from Oslo's Medieval Park excavation shed light on one of history's most popular pastimes: playing games and gambling.

One wooden gaming-piece, a wooden gaming-board, a chess piece, and three soapstone gaming-pieces.

It’s a small collection. Nonetheless, they represent favourite pastimes of both aristocrats and regular Joes from the Middle Ages: playing games.

For now, the gaming-pieces are carefully stored away in plastic bags immersed in water, at the make-shift field offices of the archaeologists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research, NIKU. Whether they will eventually be displayed anywhere remains to be seen.

Since August last year, the NIKU archaeologists have been unearthing remains of medieval Oslo, a dig that has among other things resulted in the first runic bone finds in Oslo in more than 30 years, and a unique and beautifully carved handle picturing a king holding a falcon.

Mark Oldham, project manager for the excavation, says they are pleasantly surprised by the finds.

“It’s a little surprising – even if we suspected it might be the case – that we’re finding so much in an area that has previously been excavated when building railways. We thought there would be more smaller pockets of deposits between modern foundations or walls. But we’ve unearthed large areas of intact archaeological layers with a number of structures such as streets and houses, as well as thousands of smaller finds”, he says.

And now also traces of the leisure activity of playing games.

Gaming-pieces for the average citizen

The gaming-pieces were found in the medieval mud just about two weeks ago.

“They could have belonged to anyone – rich or poor, old or young”, says archaeologist Oldham.

“All you needed was a piece of wood, and you could carve this yourself. All of these are made out of materials that were readily available, using knowledge and skills that most would have”, he says.

Most medieval folks could carve or knew somebody who could carve nice gaming-pieces. One of the gaming-pieces in stone is made from a fragment of a broken pot, revealed by the patterns on the rugged side as well as the curved inside.

For fun, and for money

“We have plenty of these kinds of gaming-pieces from medieval Trondheim, dated to the 13th and 14th century”, says Chris McLees.

McLees is an archaeologist with NIKU’s office in Trondheim, in central Norway. Called Nidaros in the Middle Ages, Trondheim was the capital of Norway’s first Christian kings.

Just over 30 years ago, McLees wrote what has become a reference work on the topic of games in the Middle Ages, Games people played.

Sciencenorway.no emailed McLees photos of the finds from Oslo, in order to find out more about the use of these particular gaming-pieces.

“It’s quite obvious that playing games was popular at this time”, McLees says.

“People played games all the time, in various settings. At home, while having a beer at the tavern, anywhere and anytime really”, he says.

So much so that a bit of a gambling problem seemed to spread in society, according to the archaeologist.

“People were gambling, not just with the kind of gaming-pieces recently found in Oslo, but also with dice. We’ve found lots of dice in the medieval towns”, McLees says.

The gambling problem become so widespread that Magnus Lagabøtes city laws, from around 1276, addressed the issue. Anybody found gambling with money would have it confiscated and would be fined.

The backgammon of back then

The wooden gaming-piece found in Oslo most likely belongs to a game called tables, according to McLees – a precursor to modern day backgammon.

The game was initially popular among the highest aristocratic groups, but filtered down to other parts of society, particularly in the towns.

“They would play for fun, but tables was well suited for gambling”, says McLees.

The widespread popularity of the game is evident in the number of pieces the archaeologists have found in the medieval towns – in Norway, and Europe.

While the more luxurious aristocratic pieces, which would for instance be beautifully carved in ivory or the like, are found in museums, or perhaps in European castles here and there, town excavations typically reveal pieces in all sorts of quality.

“We find more simple objects, carved in bone, antler, or in this case wood – anything that can be easily carved. Some have beautiful patterns, with carved animals and birds, or simple circles”, McLees says.

A travel-size gaming-board

The square wooden board with carved patterns of squares and a cross in the middle, is a board for a game called merels, according to McLees.

The idea of the game is to get three of your pieces in a row.

“These are so simply carved, somebody could say let’s have a game, take their knife and just carve this on the back of a piece of wood”, he says.

The gaming-board from the Medieval Park in Oslo, however, is a bit different, in two aspects.

“Somebody has taken a bit of extra care in carving this, with the x in the middle, I haven’t seen that before”, the archaeologist muses.

The size is also surprising, as the board nearly fits in the palm of a hand.

“My goodness, that’s interesting!”, McLees exclaims.

“This is an unusual example in its size and would require very small gaming-pieces to play it. Maybe it’s a child’s game. Or someone found this piece of wood and just decided to use it for this. Perhaps it was like a little travel game? Somebody decided to take this on a journey, I’ll put it in my rucksack and play some merels on the journey.”

One man who brought merels with him on the journey to the afterlife, was the Viking buried in the Gokstad Viking ship.

“They found a double-sided game board for the popular Viking game hnefatafl, and on the other side a board for merels. So merels goes back at least to the Viking age in Norway”, McLees says.

A rough chess pawn

The other wooden piece found in Oslo, is probably a chess piece. Possibly a pawn.

McLees notes that it has certain formal similarities with gaming-pieces used for the Viking game of hnefatafl.

However, this piece probably dates to the 13th or 14th centuries, by which time hnefatafl had been replaced by chess.

As with tables, chess was originally the preserve of the aristocratic classes before it filtered down to the ordinary urban population.

Older chess pieces were often more abstract in form, as chess came to Europe from North Africa, and the Muslim religion did not allow reproduction of human figures.

“Also in Norway we find abstract pieces, but in the 1100s at some point, things go figurative”, McLees says.

“The pieces placed on the boards portrayed society, kings, queens, bishops and the ordinary people. And people spent time carving beautiful pieces”.

The Oslo-piece is not of the finer sort.

“Somebody knows it has to look like this to be a chess pawn, but it’s a bit rough. This is an ordinary person’s chess piece”, McLees says.

- READ: A bone and a stick inscribed with Norse runic text found in Oslo

- READ: New runic find from medieval Oslo – this time it’s a name tag

A spindle whorl that became a gaming-piece?

The archaeologist in Trondheim is less certain about the soapstone pieces.

“They are a bit more ambivalent in use, they could have been used for playing or for something else”, he says.

McLees believes the one with the hole in it might be a spindle whorl, an object used to weight spindles when hand-spinning yarn.

According to Mark Oldham and the team in Oslo, the stone with the hole in it is probably too thin and light to be a spindle whorl. They still categorise it as a likely gaming-piece.

“There are gaming-pieces with holes in the middle – but in these cases I’ve usually interpreted them as gaming-pieces reused as spindle whorls.”, says McLees.

“I can’t think of a reason why you would need to make a hole in a gaming piece. It’s difficult to arrive at a conclusive interpretation. To my mind, it could be a spindle whorl, a gaming-piece, or neither”, he says.

People will be people

In any case, the large amounts of gaming-pieces found in medieval towns shows that humans haven’t changed very much in certain respects.

“Life may have been harder for them in certain ways, but they were still socializing with each other, they enjoyed each other’s company, they wanted to have fun, to gamble, to use their minds – some of these games required that you used your intellect”, says McLees.

It could also have been competitive, as well as something entertaining to watch.

“People would have sat around and watched people playing chess and enjoyed the competitive environment, perhaps placed some bets”, McLees says.

“All these objects that we find, were intricately involved in people’s lives. Somebody made these gaming-pieces, knew how they had to be formed, and how they had to be used. All these little objects have so much to say about their society”.