Why some Iron Age women chose exotic jewellery

The highly untraditional choice shows a desire to stand out in a crowd, according to one archaeologist.

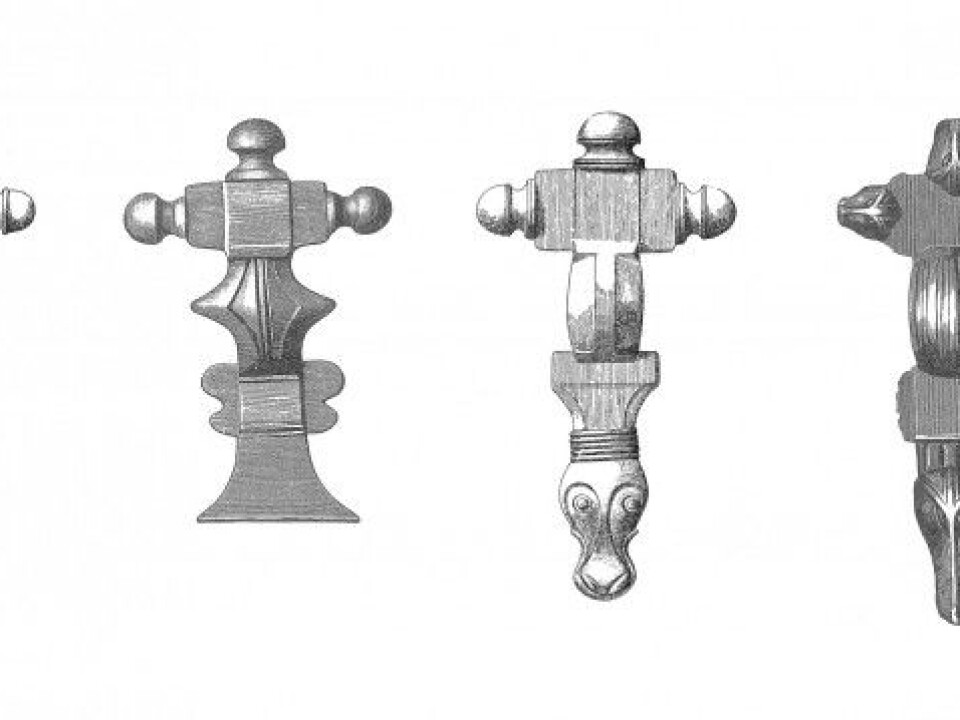

The brooch in question is fairly typical of jewellery from southern Norway during the Iron Age: A series of faces surround a rectangular plate, while animal figures dominate the centre section. But a raised spiral decoration on the surface of the brooch is most certainly not Norwegian. Instead, it more closely resembles decoration found on brooches from Denmark and southern Sweden.

This mashup of different Scandinavian designs on one piece of jewellery was highly unusual during the Iron Age.

“I am convinced that this represents a desire to stand out,” says archaeologist Ingunn Marit Røstad, from the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo. Røstad’s doctoral thesis is based on 1800 pieces of Iron Age jewellery dating from 400-700.

Around the year 500, different areas of Norway were characterized by clear differences in jewellery designs. At this time, which archaeologists call folkevandringstid, or the age of migration, Norway did not exist as a nation but as many smaller kingdoms. Each area had its own jewellery traditions, which Røstad says were difficult to contravene.

“I think there were strict rules that governed who was allowed to wear different kinds of jewellery,” she said. “There’s a lot of evidence to suggest you couldn’t just go out and wear whatever kind of jewellery you wanted.”

Laws governing jewellery use

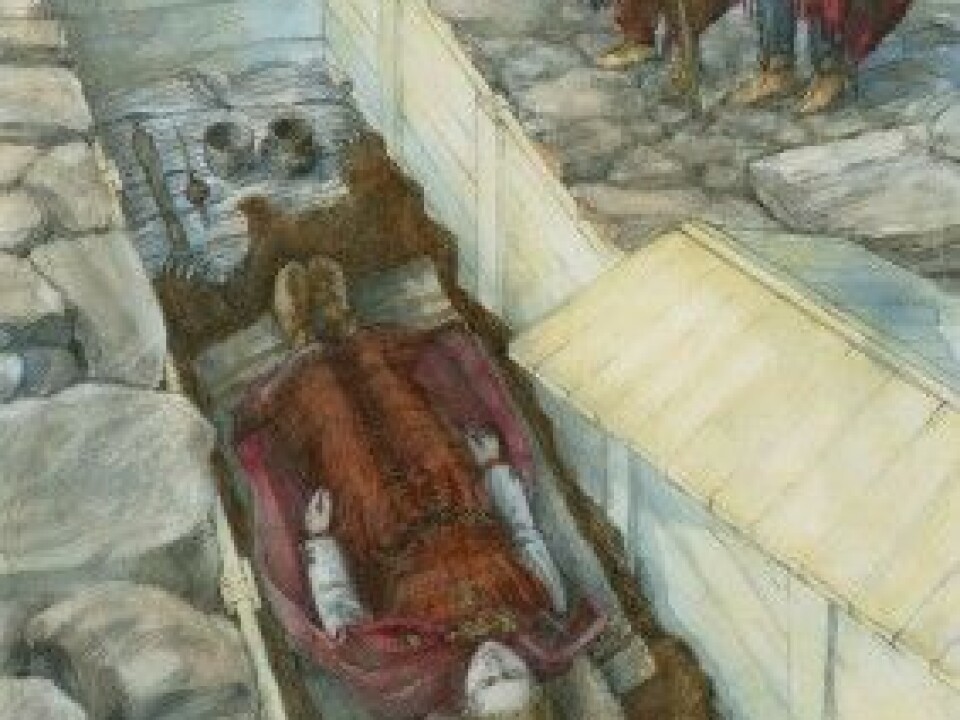

Røstad says it appears that a few women during this time did wear jewellery that showed a foreign influence. This is based on what has been found in very richly appointed gravesites, which “show that not just anyone could wear this kind of jewellery,” she said.

There are no written sources from Scandinavia at the time, but we know that during the Middle Ages in Europe, there were laws governing who could wear jewellery made from silver and bronze. The use of some colours and fabrics was also quite restricted.

While jewellery from the 400s in what would later become Norway was often quite similar from region to region, people during the next century seemed to need to show regional disparities, if evidence from gravesites is to be believed. Røstad thinks people used jewellery to express these differences.

Jewellery was “very visible evidence of where you came from,” she said. “This was probably important visual information at a time when writing was not in use.”

Mix and match

Yet mixed in with this regional jewellery are bits of bling inspired by designs from distant regions. These pieces were generally not imported; minute differences in the designs suggest that local craftsmen had made them.

For example, archaeologists found a mould in eastern Sweden that could be used to make jewellery typical of Rogaland, in western Norway. The jewellery has only ever been found in Rogaland. It may be that the craftsman took the mould with him when he settled outside Stockholm, but then was unable to sell jewellery designed according to western Norwegian traditions to the local population.

Even though you might have connections to several areas, you could still comply with local jewellery traditions. Those who mixed and matched their jewellery stood out. But why would they want to do that?

Jewellery as politics

Røstad thinks the explanation for the mix-and-match jewellery may be political. By the 6th century it had probably already become customary for the upper classes to raise each other's children, a practice known from later times. The children could move back to their home region when they were adults and bring the traditions of the foster family. People from different areas could also marry across regions.

“This was how leaders built kindred relations and alliances. These relationships involved shared obligations, which made it harder to go to war later. This was something that could ensure a clan’s continued existence in a society before there was a nation-state,” says Røstad.

An Iron Age woman who wore jewellery with a foreign influence clearly had contacts in remote areas that the family wanted to show off. Later, Vikings would also use jewellery to make a statement—except in their case, it was to show off their status with jewellery from afar.

Artistic expression rather than political statements

It’s impossible, of course to know exactly what was intended with the regional variations that are found in different kinds of jewellery from this time. But Elna Siv Kristoffersen, an archaeology professor at the University of Stavanger who has also studied jewellery from this period and who evaluated Røstad’s thesis, thinks that the differences in brooches were not necessarily political.

For example, she says, regional variations in cross-shaped brooches may be due to differences in how craftsmen interpreted shapes and styles, she said.

“Maybe it was a way for different craftsmen to express their interpretation of same idea,” says Kristoffersen.

Røstad however, believes that the variations are so systematic that they are not due to random preferences or individual style.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no