Northern carnivorous dinosaur was a vegetarian

An overlooked clue preserved in 123 million-year-old sandstone deposits debunks the belief that meat-eating dinosaurs roamed the island archipelago of Svalbard

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

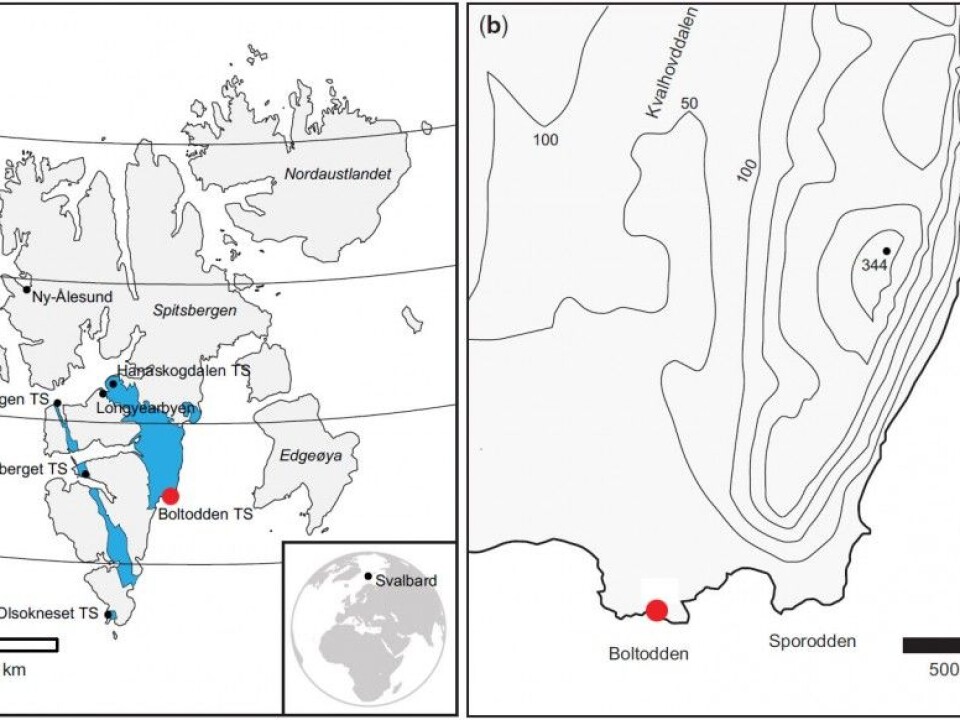

The largest collection of dinosaur tracks on the Norwegian arctic island archipelago of Svalbard is found on the southeastern coast of the main island of Spitsbergen, in a place called Boltodden.

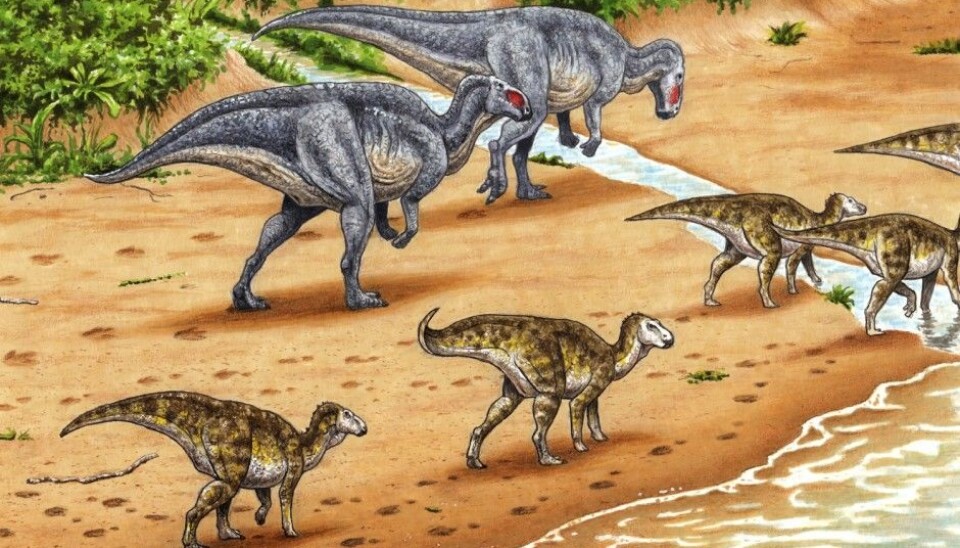

Although Svalbard now lies at roughly 70 degrees N latitude, 123 million years ago, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, Svalbard was farther south, more at the latitude of Fairbanks, Alaska. That might not sound very hospitable to dinosaurs, but the climate was so much warmer and wetter then that forests of ginko trees and conifers covered Svalbard – and dinosaurs wandered its reaches.

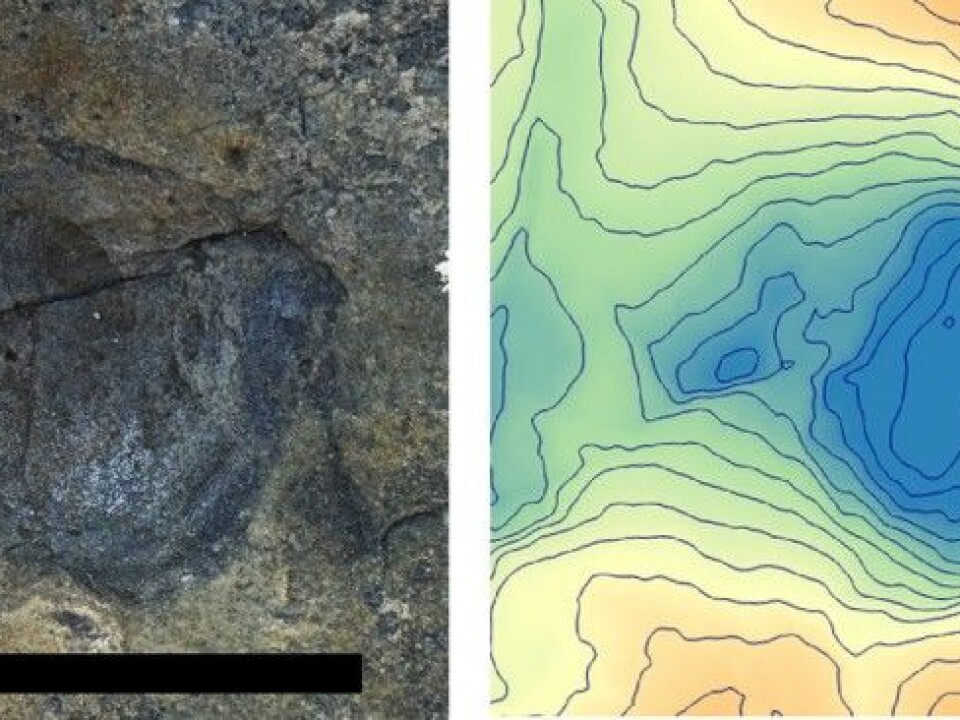

In 1976, an American petroleum geologist named Rosalind Edwards found some of the dinosaur tracks left at Boltodden and described them as characteristic of a medium-sized carnivorous dinosaur called a theropod – the first and only carnivorous dinosaur ever found on the island.

The tracks as she described them were unmistakably from a carnivore, 30 centimetres long and with the clear imprint of a claw. And most tellingly, they were in sets of two, meaning that the dinosaurs that left them walked on two legs. Vegetarian dinosaurs characteristically walk on all fours.

From two to four

Thirty-eight years later, in the summer of 2014, the Norwegian palaeontologist Jørn Hurum from the University of Oslo’s Natural History Museum and his colleagues returned to Boltodden to re-examine Edwards’s find.

The first thing they noticed was that there were many more dinosaur tracks here than Edwards first reported. In fact, they realized, the area held the largest collection of dinosaur tracks in the entire archipelago.

And secondly—the tracks from the carnivorous theropod that Edwards had reported in 1976 had not been left by a creature walking on two legs after all. The dinosaur that left these tracks walked on all fours. And that meant it had to be a herbivore.

“No carnivorous dinosaur has ever been found to walk on all fours, except possibly Spinosaurus,” says Hurum.

Spinosaurus was a giant among carnivorous dinosaurs. Its great weight may have forced it down on all fours from time to time, some researchers believe.

But the tracks on Svalbard were too small, and were older than Spinosaurus. The tracks left by this four-legged dinosaur led Hurum and his colleagues to a new conclusion: The tracks had to have come from an ornithopod, a vegetarian dinosaur.

Tricked by the sand

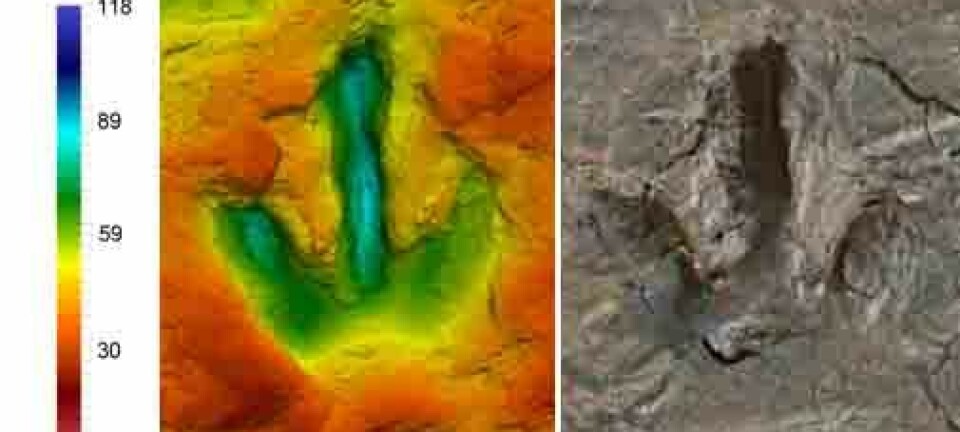

Although the tracks were clearly left by an ornithopod, Hurum and his colleagues still had a mystery to solve. The tracks from the hind feet seemed to show an imprint from a claw. But herbivores don’t have claws.

The answer, the researchers realized, was that there were no claws. The toes were round, but the condition of the sand when the dinosaurs walked there made it look like the toes were actually sharp, like claws.

“Imagine that you are walking on a sandy beach. The imprints left by your toes are round. But then the wet sand collapses a bit and runs into the track from the sides and towards the bottom. That causes the imprint to look almost like claws,” says Hurum.

“Water-saturated sand partially collapsed at the tracking surface, resulting in distortion at the distal end of the digits and producing an artificially narrow toe outline, including a sharp claw-like morphology,” the researchers wrote in their scientific paper on the find. “The high moisture content of the sediment is inferred

from the depositional setting, which was probably a beach.”

Right dinosaur, wrong place

The tracks still pose a huge puzzle for the scientists, because the Svalbard of the Cretaceous period, or 123 million years ago, was close to Greenland and North America, but was effectively isolated from Europe.

However, the tracks of a four-footed ornithopod like this were much more typical of Europe of the period. And these dinosaurs did not fly, they could only walk. So how did they get to Svalbard?

“One possibility is that quadrupedal ornithopods were more widespread across Greenland/North America at this time than recognized but (are) poorly represented by body or trace fossils, which seems likely to be at least partly true,” the researchers wrote. “Alternatively, a potential route of terrestrial connectivity that is not currently recognized... permitted dispersal between Svalbard and Europe.”

In other words, researchers may have lost the only carnivorous dinosaur ever found on Svalbard, but they have a new mystery to solve: how did this dinosaur, only known from Europe, find its way to the Svalbard of that time?