Denmark's iconic runestone from the Viking Age may not actually be from the Viking Age, claims a Norwegian archaeologist

The large Jelling stone was commissioned by a bishop in the 1100s. Not by Viking King Harald Bluetooth in the late 900s, according to researcher Håkon Glørstad.

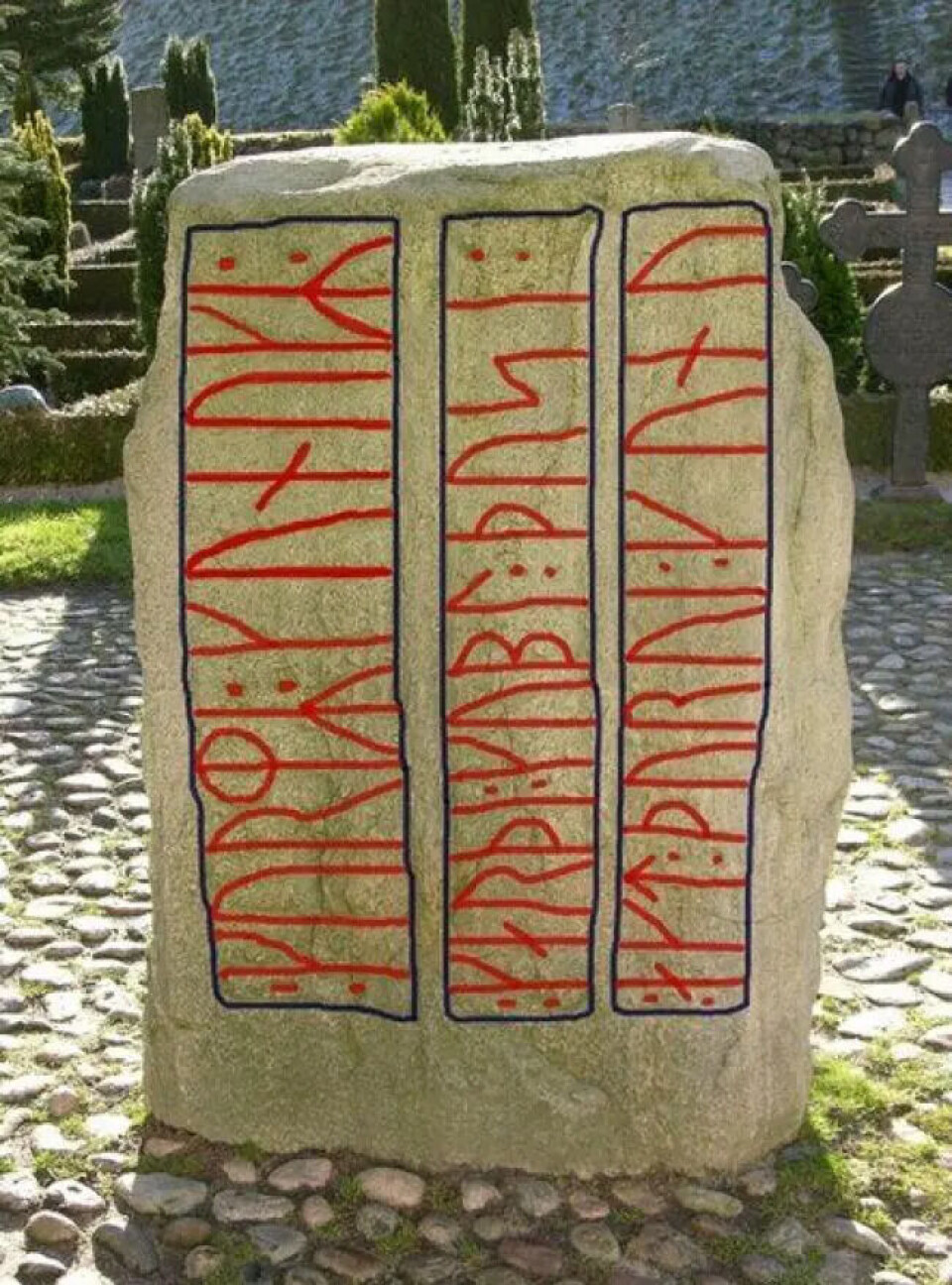

In Jelling in Southern Denmark, there are two runestones.

The small and the large Jelling stone are iconic symbols of modern Denmark.

On the small Jelling stone, the name Denmark is used for the first time. On the large Jelling stone, the Danes have also become Christians.

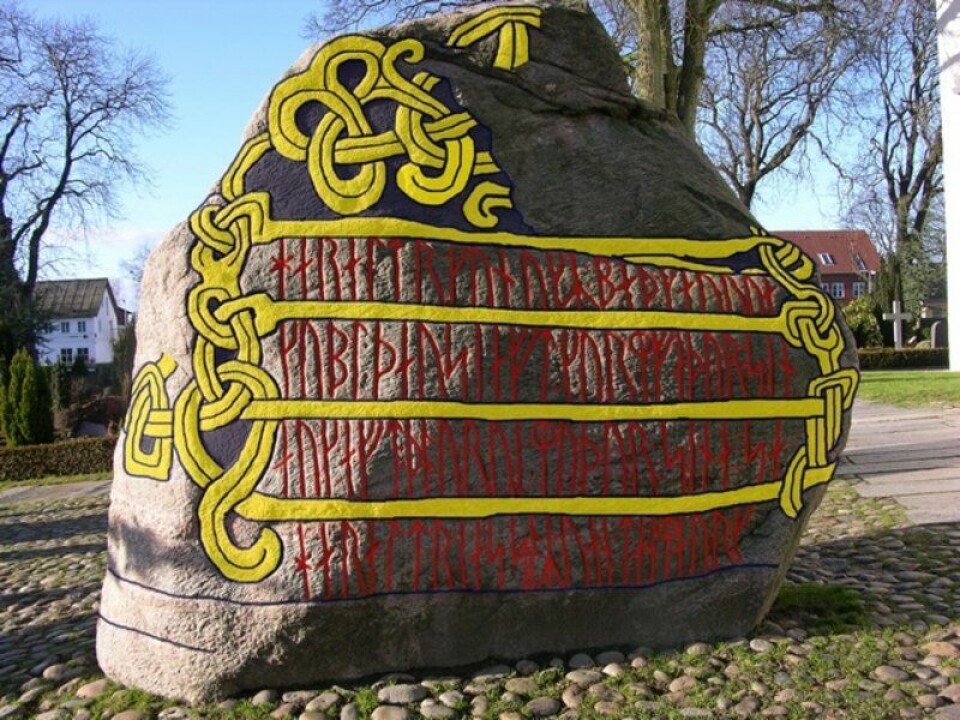

The text on the large stone reads:

'King Harald ordered these monuments made in memory of Gorm, his father, and Thyra, his mother; the Harald who won all of Denmark and Norway for himself and made the Danes Christian.'

The stone explicitly credits King Harald Bluetooth with its creation.

That would mean it was made in the latter half of the 900s.

But is it true just because it is written?

The challenger

Archaeologist Håkon Glørstad is not so sure about that.

In the latest issue of Viking, the Norwegian archaeological yearbook, he argues that the stone was instead commissioned by a bishop in the 110s as part of a nation-building effort at the time.

It's a bit like a Danish archaeologist claiming that the Oseberg Viking ship is not a Viking ship.

Glørstad acknowledges that his Danish colleagues are unlikely to embrace his new theory. 'To have an opinion on Jelling is to have an opinion on Denmark as a nation,' he writes in the article.

"I expect many will disagree, find it unnecessary or even provocative, and that several will attempt to refute it," Glørstad tells sciencenorway.no.

"But I believe the value of research lies in challenging established ideas rather than just confirming them. I've tried to examine the material with a different perspective than usual," he says.

A truly unique stone

Glørstad's primary area of expertise is actually the Stone Age. However, as the former director of the Museum of Cultural History, he advocated for a new Viking Age museum. When the pandemic hit, he immersed himself in Viking Age studies and became particularly interested in a book about Jelling.

At first, he found the story touching. The effort put into creating a narrative of Danish history centered around this site and these stones impressed him.

"But then it started to feel strange. There were many things I couldn't make sense of," he says.

There are indeed many unusual aspects of the large Jelling stone, Glørstad writes in his article.

No other stones from the period resemble it, and it is the first of its kind to combine several unique features, according to Glørstad.

For example, the text on the stone is written horizontally, the way we write today.

"That was not a common way to create runestones in the Viking Age. Back then, texts were written vertically," says Glørstad.

He also believes the content is atypical for the Viking Age.

"The inscription resembles 12th-century grave slabs, which often feature a summarising and boastful account of the deceased's achievements," he says.

The type of rock used also does not match the stone choices typical of the Viking Age for such purposes, according to Glørstad.

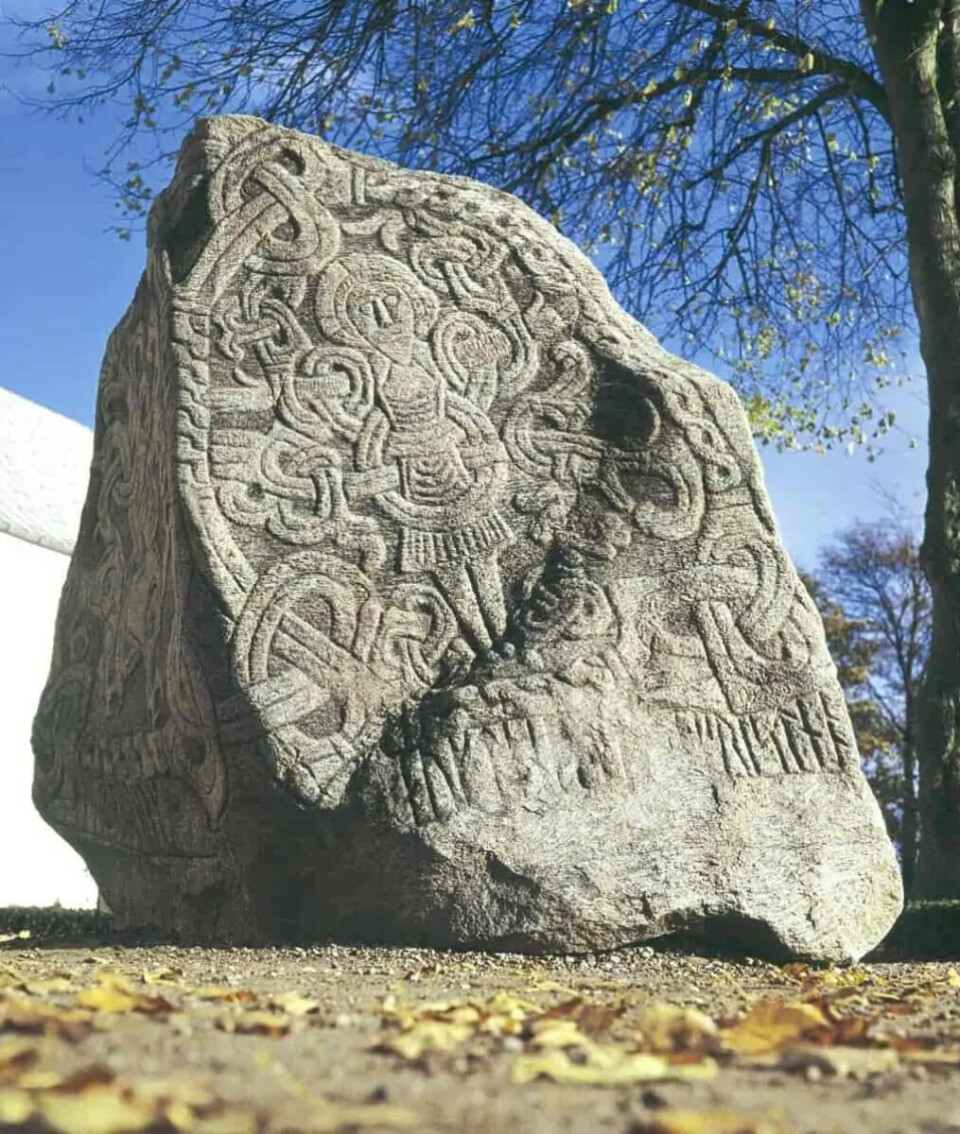

He further notes that the style of the carvings and figures is also uncharacteristic.

Moreover, during Harald Bluetooth's time, people lacked the intellectual capacity required to create such a compllex stone.

Jesus and the lion

In addition to the inscription itself, the large Jelling stone features a large image of an animal – most likely a lion – and an image of Jesus.

These motifs are unusual in a Viking Age context, according to Glørstad.

The depiction of Jesus is the only one of its kind from the Viking Age, he points out.

Lions, however, were extremely popular – in the 1100s.

"Many have pointed out that this lion resembles an emblem. And it was very popular to use the lion as such a symbol in the 12th century. Several Norwegian and Danish kings did so," says Glørstad.

He argues that the stone is only truly unique if one believes it dates from the Viking Age.

However, it fits quite well into what is referred to in Denmark as the Valdemarian Age, which began in 1157.

The popular Viking Age

Denmark was in the process of unifying as a state, and creating a shared national history became important. Kings were fascinated by Viking rulers, and the upper class learned to read runes.

This is where Glørstad finds Bishop Absalon, a close friend and adviser to King Valdemar the Great, who had his own personal Nordic stonemason.

"Absalon was committed to building Denmark on a historical foundation to legitimise Denmark's place in Europe and the world," says Glørstad.

The mixed styles, motifs, and stone choices that do not match the Viking Age, along with the language, stand out. The language on the large Jelling stone is more archaic than on the smaller one, even though the smaller stone was created earlier.

This, according to Glørstad, does not point to Harald Bluetooth, as he would likely not have created the stone in this way.

However, a bishop during the Valdemarian Age, drawing on inspiration from how 'the old days' were remembered at the time, could have done so.

'In my opinion, it is likely that Archbishop Absalon commissioned the stone. He had clear motives for erecting such a stone at Jelling and sufficient resources to carry it out,' Glørstad writes in the article.

Harald tried but failed

One of the strongest arguments supporting Glørstad's theory comes from archaeological excavations.

The area around and beneath the Jelling stones have been excavated several times.

Under the stones, archaeologists have found traces from the Middle Ages, including medieval graves and foundations.

"The stone is also anchored in a way that resembles the construction of the nearby stone church, which dates from the 1100s," says Glørstad.

Then there are the stories from medieval chroniclers. Both Saxo Grammaticus and Sven Aggesen wrote about a large stone that Harald Bluetooth failed to bring to his mother Queen Thyra's grave.

Harald forced his army to drag the stone towards Jelling, but a rebellion broke out, and Harald had to flee the country.

If the large runestone had actually stood in place during their time, Glørstad argues, Saxo and Sven would have mentioned it instead of focusing on Harald's failed attempt.

"This suggests there was a strong tradition surrounding the stone, and that Harald tried but didn't succeed," says Glørstad.

"It could have been tempting for Bishop Absalon to have the stone erected both to confirm the historical narrative and to reinforce Denmark's unity," he says.

They believe they know who carved the runes

Harald Bluetooth's mother was named Thyra.

A little over a year ago, Danish archaeologists claimed that Viking Queen Thyra was likely more powerful than previously believed.

Her name is inscribed on a total of four runestones, including both the small and the large Jelling stones. Researchers concluded that the same Thyra was referenced on all the stones.

But not only that – they also claimed to know who carved the runes, a man named Ravnunge-Tue.

Glørstad is familiar with this research but remains sceptical of the conclusion.

Without more information about what the researchers chose to include and exclude from their analysis, it is difficult to assess this work, according to Glørstad.

"They should have made more of the background material for the analysis available," he argues.

Glørstad and archaeologist Lisbeth Imer, who conducted this research, also disagree on a specific detail.

On the large Jelling stone, the name 'Thyre' is inscribed, not 'Thyra.'

Imer believes this difference is due to the formal language used on the stone. Glørstad, however, thinks it indicates the stone was created in a different era.

The writing on the stone

At the very beginning of the Jelling stone's scholarly history, around the 1830s to 1850s, some suggestions were made that it did not date from Harald Bluetooth's reign, Glørstad explains.

"But most people have relied on the text when interpreting the stone," he says.

Glørstad wants to challenge this approach.

"Historical scholarship tends to be overly submissive to writing and the written word, often interpreting and organising other sources according to what the text says. But sometimes we write how things should be, not how they actually are," he says.

"In this case, the text has completely dominated our understanding of the stone and its place in history," he says.

Still a runestone from the Viking Age

"It's always interesting when new perspectives and approaches to this material emerge," says Adam Bak.

He is a museum curator at Kongernes Jelling, the visitor centre that includes the Jelling stones, which are part of the National Museum of Denmark.

However, he believes the new theory does not hold up.

"At first glance, I don't think the article gives me any reason to change the current interpretation we have," he says.

Harald Bluetooth's court had the knowledge

"It's good to have a discussion, and he presents his arguments well. But some points are open for discussion," says Anne Pedersen, senior researcher at the National Museum in Copenhagen and an expert on the subject.

She specifically disagrees with Glørstad's conclusion that the royal court during Harald Bluetooth's time lacked the intellectual capacity to create a stone like the large Jelling stone.

"That's simply not true," she says.

Pedersen points to several factors indicating that Harald Bluetooth's court possessed the necessary intellectual capacity to commission such a remarkable stone:

- Workshops producing advanced goldsmith work, such as the Hiddensee treasure from Rügen in northern Germany.

- Silver coins associated with the king featuring Christian motifs, including depictions of the crucifixion.

- Geometric knowledge required to create the large monuments constructed in Jelling during that period.

- There were likely people at the court with knowledge of Latin.

- A Danish delegation was sent to a meeting in the Ottonian Empire in 973, according to written sources.

"When the royal authority was developed enough to send a delegation to the Ottonian Empire, it clearly had the intellectual capacity to create the large Jelling stone," she says.

Artefacts from the 10th century with similar symbols

Pedersen also dismisses the argument that chroniclers wrote only that Harald attempted but failed to erect the stone.

"It's just as likely that they didn't mention it because they hadn't seen it themselves," she says.

Pedersen further points out that artefacts from the 900s exist featuring serpent-like creatures similar to those on the Jelling stone.

"Glørstad makes a detailed argument for a later date but doesn't give the same weight to an analysis of the context in the 900s," says Pedersen.

"An article like this makes you reflect – where do our arguments stand, and are they still valid? And I believe they are. There are strong cultural-historical arguments supporting the idea that the large Jelling stone was erected at the time most scholars agree it was," she says.

Absalon's runestone clearly not from the Viking Age

Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt, one of the researchers behind the study claiming to have identified who carved the large Jelling stone, also challenges Glørstad's theory.

She works at the Swedish National Heritage Board and is both an archaeologist and a runologist – a specialist in runes.

"My initial reaction to Glørstad's theory was surprise," says Kitzler Åhfeldt.

She points out that there is a runestone in Scania that was indeed commissioned by Bishop Absalon in the late 1100s. The inscription on this stone clearly indicates it is not from the Viking Age, she argues.

The large Jelling stone, however, is most likely from the Viking Age, according to Kitzler Åhfeldt.

Do not underestimate Viking rune carvers

Glørstad has criticized Kitzler Åhfeldt and her colleague Lisbeth Imer for not providing enough transparency regarding their analysis of who carved the large Jelling stone.

Kitzler Åhfeldt acknowledges that more data could have been included in the appendix.

However, it is not as extraordinary as it might seem that researchers have identified the person who carved the large Jelling stone, she explains. In Sweden, several well-known rune carvers have been identified, and the method for recognising them is well-documented in other publications. The analysis of Danish runestones builds upon this prior work.

"I’m pleased that he shows such great interest in the details of our research and curious to know if he has suggestions for further analysis," says Kitzler Åhfeldt.

She also disagrees with Glørstad's claim that there was no intellectual environment capable of creating the large Jelling stone during the Viking Age.

"Several rune carvers possessed exceptional skills, and many were more knowledgeable than those around them. We should not underestimate them," she says.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.