Soviet Cold War oceanographic surveys opened up to western scientists

A treasure trove of Barents Sea fisheries data stored for decades in Murmansk can help determine the fate of future offshore oil and gas exploitation in the region.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

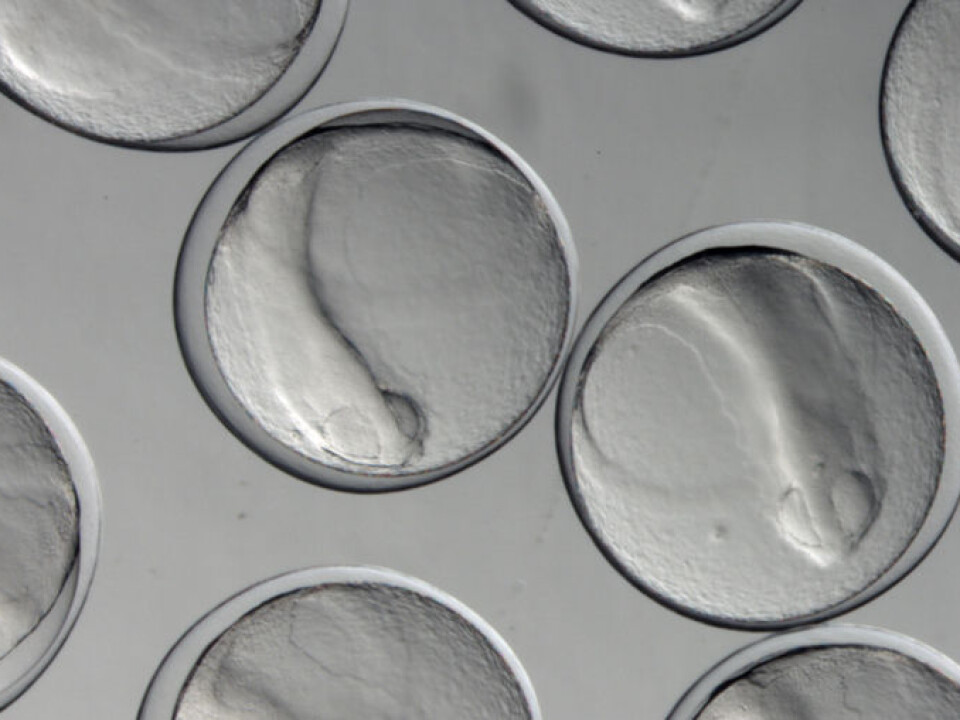

The cod is a fish that hedges its biological bets by producing enormous amounts of roe. A mature female can produce millions of eggs. But how many of these future fishes survive, and where? The answers are vital for protecting cod stocks and could determine where future offshore drilling developments will be allowed.

Soviet research voyages from the Cold War era collected important data for modern research on the first weeks in the life of Arctic cod.

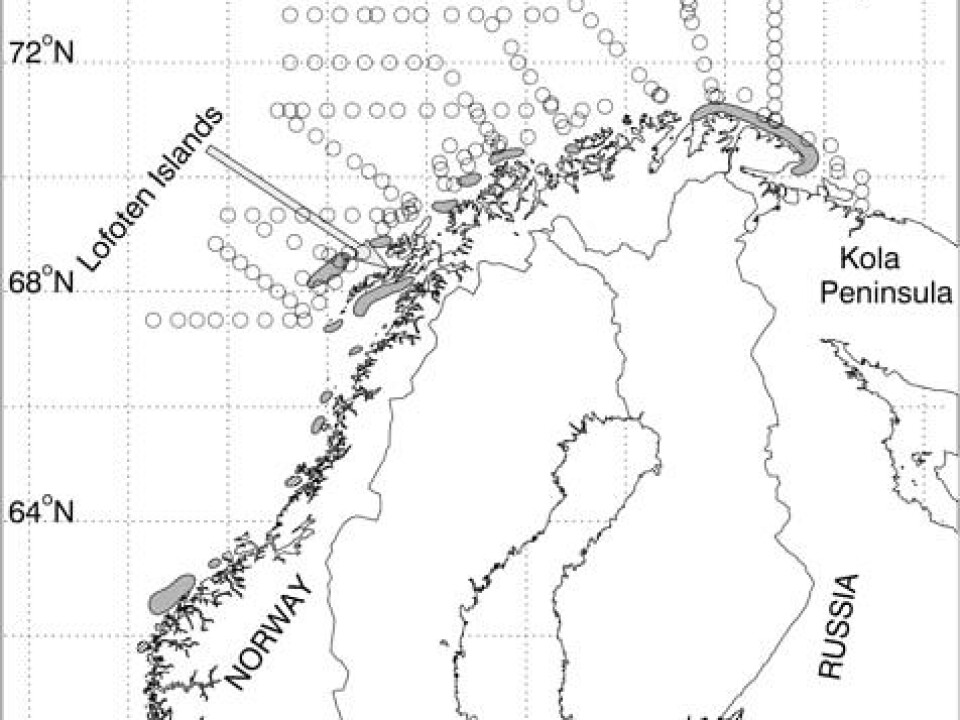

From 1959 to 1993, Soviet − and in the last few years, Russian − scientists cruised the Barents Sea and off Norway’s Lofoten Archipelago to collect data. Their data collection was far more extensive than material gathered by Norwegians during the same period.

The data have been stored in Murmansk and have now been digitalised.

Marine biologists and other scientists can now use the comprehensive database in their computerised models.

Little to go by

“We have precious little empirical data showing how eggs actually survive,” says Leif C. Stige, a researcher at the University of Oslo’s Centre for Ecological and Evolutionary Synthesis (CEES).

Stige is one of the researchers behind a new Norwegian-Russian study based on the data from the Soviet oceanographic voyages.

These voyages provide a rich bank of information for modern research.

The data are in the hands of the Knipovich Polar Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography, known as PINRO. PINRO, based in Murmansk, has been collaborating with Norwegian researchers for years.

Annual voyages and carpet bombs

The Cold War did not prevent the USSR from running annual voyages with research vessels off the northern coast of Norway.

They took samples of cod eggs, larvae and zooplankton. Their goal was to learn about the first weeks of a cod’s life.

What is well known is that the female cod is highly prolific – she essentially carpet bombs the sea with her eggs.

After the female spawns along the Norwegian coast, the eggs are left to themselves, in a pelagic drift riding ocean currents. The female cod is exhausted by the process and makes her way back into the Barents Sea.

Mortality rate of 97 percent

Researchers from Norway and Russia are using the PINRO data to estimate the proportion of cod eggs that survive hatching and live for the first few weeks.

“We see that it varies from year to year, from one to nine percent. An average of three percent of the eggs become larvae,” says Stige, from CEES.

In other words, 97 percent of the eggs die between spawning and hatching.

With several other eyes of needles to pass through, their tribulations don’t end there. Losses are also huge among larvae, fry and small codfish.

They aren’t reasonably safe until they become large adults, but then they risk being caught on hooks or netted in trawls.

Jigsaw puzzle

“We’ve always known that the mortality rate for fish eggs was huge. But this data provide us one of the missing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, and tell us which of the cod's life stages has the highest death rates,” says Bjarte Bogstad, a researcher at Norway's Institute of Marine Research.

Bogstad has also participated in the new study, which has been published in ICES Journal of Marine Science.

Earlier studies of eggs from various cod stocks have shown differing results. These have all been based on shorter timespans than the Norwegian-Russian study.

The new results will contribute to more accurate models, especially in relation to how the ecosystem develops along with climate change.

Oil spills

The survivability of eggs is also a key issue of contention in terms of the risks posed by prospective oil and gas projects off the coast of Lofoten and other spawning waters. The cod's egg and larval stages are also the most vulnerable to the impact of oil spills.

“If an oil spill kills a certain share of eggs or larvae, let’s say ten to 15 percent, you might expect a loss in recruitment in that range,” says Stige. Biologists use the term recruitment to mean the population that survives to adulthood from a specific age group.

But he explains that these kind of recruitment estimates are not that straightforward. The question is whether oil slicks kill eggs and larvae that had little-to-no chance of maturing anyway, or whether these were the infant cod that were most likely to be the foundation for the next generation of the stock.

Stige says it is likely that the three percent of the eggs that survive are not evenly distributed in ocean waters. Scientists are keen to learn more about how the survival from cod eggs to larvae varies in different parts of the ocean.

Haddock are tougher

The new study also focuses on haddock in the Barents Sea. The survivability of this fish is higher than among cod, as nearly one egg in ten makes it to the larval stage.

Several Norwegian research institutions worked with PINRO on the digitalisation of the Barents Sea data. The Norwegian oil and gas corporations Hydro and Statoil are interested in oil and gas exploration in these waters and have contributed with financial backing.

Long contacts

The research voyages ended in 1993, presumably because the Russians lacked funds to continue in the immediate post-Soviet period.

Norwegian and Soviet marine researchers have at times had different approaches to their science.

The PINRO researchers were pioneers in being concerned about the entire ecosystem, a point of departure which is now nearly a mantra in oceanography.

--------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling