Mapping marine life before oil drilling starts

Foul-smelling bubbles rise from the floor of the Barents Sea. Living organisms in these depths are being studied before the oil and gas industry starts drilling operations.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The little vessel sweeps a beam of light across an expanse of plain. A dark crater appears. The vessel pauses over it a few seconds, taking pictures.

This could almost be a moon landing, but the vessel is a remote-controlled submarine. The crater is 460 metres beneath the trawler Polynya Viking.

The fishing boat rises and falls in the Barents Sea swells. Today it has researchers aboard rather than fishermen. Sabine Cochrane and her colleagues are scouting life forms beneath these chilling waters.

Oil drilling meets marine life

The development of the Goliat oil and gas field has begun. Operations to pump up the black gold deep beneath the seabed will start in a few years.

How will the oil and gas extraction impact the diversity of marine life in this subsea moonscape? Researchers from the Arctic Seas Biodiversity Project were on a mission for the operator on the field, the energy company ENI Norge.

The voyage was close to being scuttled before the scientists even made it to quay. A transport workers’ strike had paralysed much of Norway’s cargo traffic. The submarine had to be sent by a privately leased truck at a cost of €10,000.

Then a delivery firm lost track of three out of four packages with electronic gear and a new system had to be air-freighted in. Nerves were frazzled, but the hassles were long forgotten when the first images of the seabed flickered onto monitors.

Natural pollution

Motion was detected in the cone of light ahead of the sub. Was it life?

“No, we discovered a natural gas leak. This wasn’t a man-made problem,” says Sabine Cochrane.

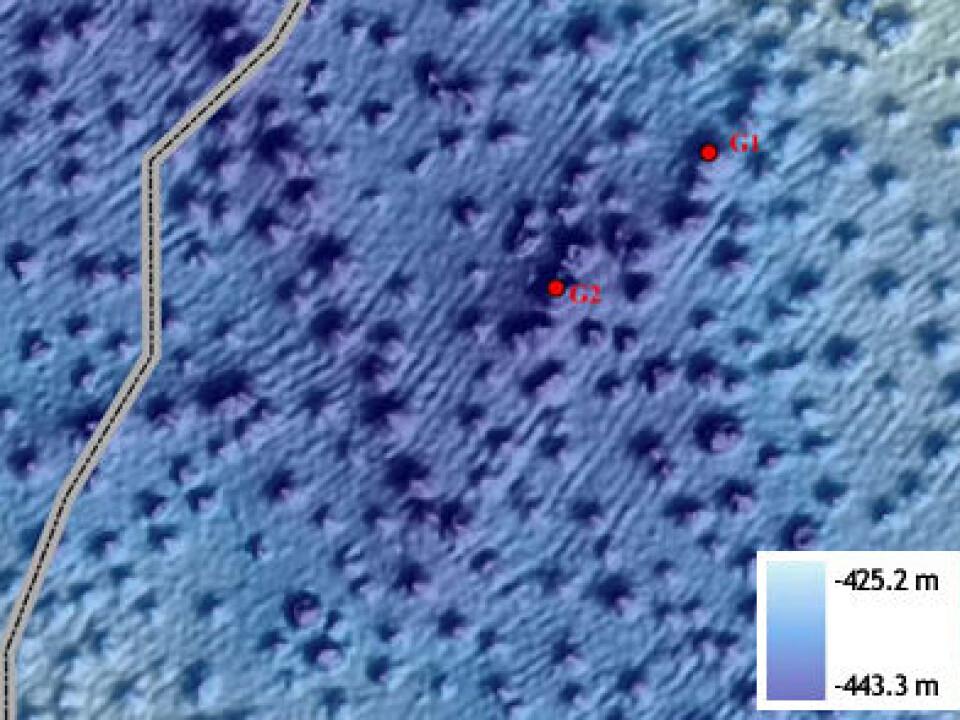

Natural gas rises through the sediments of the seabed and bubbles up into the Barents Sea. The bubbling hydrocarbons create the craters.

“We took samples from the bottom of the crater. When we brought them up to the surface they smelled like a septic tank,” says Cochrane.

Does this mean the gas is a pollutant? Although it’s completely natural, Cochrane explains it is has the same effect on the seabed as if the causes were from industrial activity.

Strange life forms

“Well over 1,000 species of invertebrates live in and on the floor of the western Barents Sea. In these craters we found scarcely more than 100,” she says.

But what organisms! The capitellid worm Heteromastus filiformis is crimson from its high concentrations of haemoglobin. This allows it to compensate for the lack of oxygen in its environment. It filled a niche.

Oil company could have been blamed

The seabed in the Goliat Oil Field area is pockmarked with craters. Oil production is scheduled to begin in 2013.

“These craters gave us something to think about. In an environmental impact study these would be classified as highly polluting," says Cochrane. "If we didn’t know they were already there and were natural, the oil company could easily have been blamed.”

------------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

External links

- Arctic Seas Biodiversity Project

- Akvaplan-NIVA's homepage

- Environmental research projects, overview by ENI Norway