Political pressure has made Norway lag behind on abortion research and foetal medicine, researchers say.

"Were not allowed to study early ultrasound because it can detect foetuses with Down’s syndrome", one specialist in foetal medince says.

In 1999, then Minister of Health Dagfinn Høybråten wanted to stop a research project at St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim.

Half of the women in the study were supposed to receive an early ultrasound to check for foetal abnormalities. Among other things, the researchers wanted to measure neck folds, which could help detect Down's syndrome.

Among other things, the goal was to explore what women who were offered an ultrasound early in the pregnancy thought about it. The researchers also wanted to find out what the women needed to know in advance to deal with potentially grave or serious information about their foetus.

Høybråten's attempt to stop the study and the heated debate that followed ended with the withdrawal of the ethical approvals for the project.

This story is not unique in Norway.

Kjell Åsmund Salvesen at St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim believes this is quite serious.

Because when political pressure stops these kinds of studies, it has consequences for the research field as a whole.

It means Norway simply falls behind in this field of research, Salvesen says.

Had to change the project to get it approved

Ten years later, in 2009, researchers in Trondheim again applied to conduct a study on early ultrasound. This time it was not politicians who intervened.

The researchers were told “no” by the regional ethics committees after the Norwegian Directorate of Health had concluded that the study violated the Biotechnology Act.

To conduct their early ultrasound study, the researchers decided to change the project.

The new goal was to find out if it was possible to detect pre-eclampsia in the mother, instead of detecting abnormalities in the foetus.

They were consequently allowed to conduct their study, as long as they did not examine the foetus.

“But otherwise we haven’t been allowed to do research on the use of early ultrasound because it can detect foetuses with Down's syndrome,” Salvesen says.

Many politicians have emphasized the argument that Norway should be a diverse society with room for everyone.

This argument has thus carried more weight than women's right to know and decide for themselves whether they want a child with Down’s syndrome or not, the professor points out.

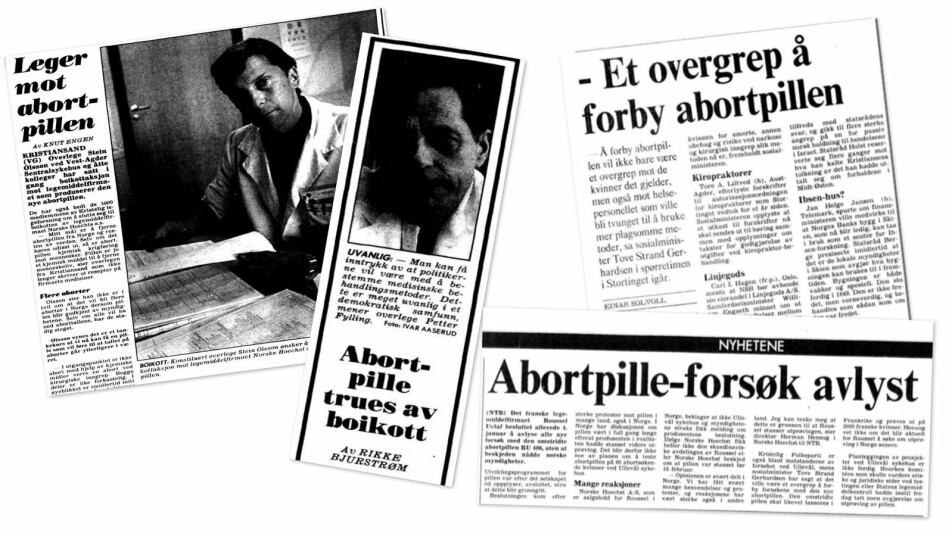

The abortion pill could have come ten years earlier

The political opposition, especially from Norway’s Christian Democratic Party (KrF), has not just been about the fear of eliminating some segments of society.

Research to make abortion easier and safer for women has also been stopped by political outcry, according to Mette Løkeland, who does research on abortion at Haukeland Hospital in Bergen.

Around 90 per cent of abortions in Norway today are performed with abortion pills instead of a surgical procedure.

Medically induced abortions are easier on a woman’s body, and abortions can be done at an earlier stage of pregnancy.

But Norwegian women could have been offered medical abortions instead of surgery ten years earlier than when the option was finally opened to them.

“Actually, we could have had medical abortions in 1989, but then the Christian Democratic Party put forward a proposal that the offer should be banned. The other parties did not support it, but because there was so much political outcry, the pharmaceutical company withdrew its application to have the drugs approved in Norway,” Løkeland said.

Is abortion possible even earlier than allowed today?

Research on abortion simply differs from other medical disciplines, Løkeland said.

“Abortion research requires much more than many other fields because there is so much political opposition,” she said.

She and her colleagues at Haukeland Hospital are embarking on a new research project being led by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden.

The goal is to find out if it is possible to have an abortion at an even earlier stage of pregnancy than what is possible today.

Currently, many women have to wait a week or two from when they find out that they have an unwanted pregnancy until they can have an abortion.

Women in Norway can decide by themselves and have the right to have an abortion within the first 12 weeks of a pregnancy. After this, they have to apply for permission to have one. Applications are considered by abortion boards at the hospitals. A first limit is 18 weeks - after this, reasons for having an abortion need to be very severe. An upper limit is set at 21 weeks and 6 days.

Abortion research has prestige in Sweden

It’s no coincidence that Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, has initiated this project.

“This research is quite prestigious,” says Kristina Gemzell Danielsson, a professor at Karolinska.

Among other things, it was researchers from Karolinska who developed the method for having medical abortions.

“It has meant a lot in Sweden that medical abortion was developed here. It has meant a lot to abortion care, and many people who work in this field are proud of the work they do,” Danielsson says.

Less pain, fewer complications

The Swedish professor believes it is very important that researchers who work with abortion also study different methods.

“I think this is an important part of women's health offerings that shouldn’t be hidden away, but where researchers should instead try to develop and improve care,” Danielsson said.

Since medical abortion was invented around 1980, the method has also changed a lot due to research.

Now, for example, the medicines used to induce abortions are given in much smaller doses. This has meant that women who choose a medical abortion have less back pain and fewer complications.

Conservative attitudes hinder research

Salvesen at St. Olavs Hospital points out that one of the four main tasks of Norway’s national health trusts is research.

“So it’s pretty serious when our conservative attitudes prevent us from doing research in certain areas. I think this is quite clear,” he said.

He also points out another consequence of Norway’s restrictive attitudes.

Norwegian women may have missed out on health services during pregnancy that are accessible in other countries and that have nothing to do with foetal medicine or abortion.

Salvesen’s own research is an example of this.

Have not been able to test for pre-eclampsia

The project Salvesen and his colleagues finally got approved in 2009 provided results.

The researchers in Trondheim showed what researchers in other countries have also found: Pre-eclampsia can be detected with a combination of blood tests and early ultrasound.

This allows physicians to prevent this dangerous condition. The method has been introduced in several countries in Europe and in the United States, Salvesen said.

However, this screening option has not been able to be used in Norway due to the political opposition to early ultrasound.

This may change as early ultrasound - meaning within the first trimester - is now going to be offered in Norway to all pregnant women who want it. According to an article on nrk.no, this will first come into place in 2022, although the legal changes were voted on last year.

“So it's a pretty exciting journey: We started in 1999, then we were stopped. Continued in 2009, and again we were stopped, but changed the project so that we could do research. Ten years later, the Parliament amends the Biotechnology Act so that we may now be able to use the method we first started working with ten years ago," Salvesen said.

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no