Free and more accessible contraceptives did not lead to fewer teenage pregnancies

Birth control pills have been free for girls in Norway since 2002. But according to a new study, this has not led to fewer abortions among teenage girls.

Norwegian girls aged 16-19 have had access to free birth control pills since 2002.

At the same time, public health nurses and midwives became authorised to prescribe them.

Since then, the scheme has changed several times to include various types of hormonal contraceptives.

The goal is to prevent unwanted pregnancies and abortion among Norwegian teenage girls.

But is the strategy working?

According to a 2010 study, abortions among women aged 20-24 were halved when women in two municipalities were offered free hormonal contraceptives.

However, a new study concludes that free contraceptives have had no impact on teenage abortions.

Most viewed

Strong decline

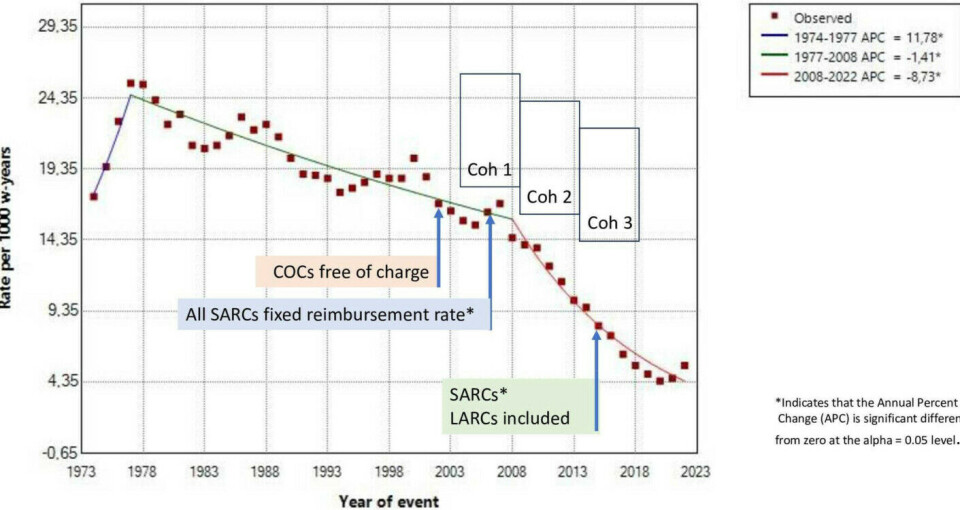

Between 1974 and 2022, the number of teenage pregnancies carried to term in Norway fell by 95 per cent.

The numbers increased at first, but then fell sharply after Norway introduced self-determined abortion in 1978.

“Norwegian teenagers are extremely responsible,” says Finn Egil Skjeldestad, a professor at UiT the Arctic University of Norway and one of the researchers behind the new study.

“Up until the age of 19-20, the numbers for abortions and births are extremely low. They’re so low that I doubt we can go any lower,” he says.

But the low numbers are not because of free and more accessible contraception. The researchers found no connection between the measures being introduced and the decline in abortions.

“The decrease doesn't fit in time-wise. Changes in teenage pregnancies and abortions don’t appear to result from these measures,” says Skjeldestad.

No more users

To study the effects of the measures, Skjeldestad and colleague Sunniva Sæbø looked at three cohorts: girls born in 1989-1990, 1994-1995, and 1999-2000.

All of these girls had access to free hormonal contraception from the age of 16.

Data for more than 170,000 girls was obtained from the Norwegian Prescription Database and Statistics Norway (SSB). The researchers looked at the years when the participants were 12-19 years old.

One finding was that public health nurses quickly took over much of the prescribing of birth control pills for young girls after 2002.

However, even though contraceptives became more available, user numbers did not increase.

About 75 per cent of the girls had been prescribed contraception at least once by the time they turned 19. The figure is the same for all three groups.

The measures also did not lead to girls who started using hormonal contraception using it for longer periods. The researchers measured this by looking at the number of renewed prescriptions.

“ Who prescribes it may not matter much for how long someone uses contraception. It likely depends more on the user's needs and possible side effects,” says Skjeldestad.

More mini pills and contraceptive implants

Changes in the free scheme have, however, led to changes in the type of hormonal contraception the girls choose to try first.

In 2002, only regular birth control pills were free. Today, almost all hormonal contraceptives are included.

For the cohort born in 1994-95, the researchers note an increase in the use of mini pills, with almost 11 per cent of girls opting to start with them. For the cohort born in 1999-2000, that number has nearly doubled.

The most significant change occurred after long-acting hormonal contraception, such as contraceptive implants, was included in the free scheme in 2015.

Almost none of the girls in the first group chose this option, compared to almost 14 per cent in the last group.

“The increase in the use of mini pills and contraceptive implants has been a desired change,” says Skjeldestad.

Both contraception methods have fewer serious side effects, like blood clots, than traditional combination pills.

2008 saw a trend change

However, the researchers did not find any effect on the abortion rate. Their finding is supported by data from other Nordic countries, where the childbirth and abortion development is similar to that in Norway – but the countries have entirely different schemes.

“We see the same 'break point' for abortions in Sweden and Denmark that happens around 2008, where the decline accelerates,” says Skjeldestad.

But in Sweden, midwives are the primary prescribers, and there was no national support scheme until 2017.

In Denmark, only doctors prescribe contraceptives, and there is no national support scheme is in place.

Skjeldestad reports the same decline in teenage abortions in England, the USA, and New Zealand.

“This happened at about the same time in a lot of countries, and we don't know why. It’s a phenomenon that we can’t fully explain,” he says.

A good study

“This is a very good and interesting study,” says Mette Løkeland at the Norwegian Registry of Pregnancy Termination (RPT).

The RPT has also noticed the significant decline in 2008, which is similar across the Nordic countries and does not coincide with measures like free contraception or more people being allowed to prescribe them.

“So other reasons must be playing a major role in the decline,” says Løkeland.

“However, we don’t have clear answers to what those reasons are. The study also shows that a large proportion of teenagers are using hormonal contraceptives, which of course contributes to reducing the number of pregnancies,” she says.

Should have been more thorough

Kari Furu conducts research on pharmaceuticals, including contraceptives, at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH).

In a 2021 study, Furu and her colleagues concluded that healthcare personnel have become important prescribers of contraceptives to young girls, and the use of contraceptive implants and hormonal IUDs has increased after these became free.

Furu finds it curious that Skjeldestad’s study looked at the effect on the abortion rate among teenagers.

“The purpose of this study was not to study the effect on the teenage abortion rate, so it’s striking that this factor is part of the conclusion,” says Furu.

Moreover, according to Furu, the data is at such an overarching level that it cannot really indicate anything about the effect.

“If you were to really look at this, you’d have to connect data at the individual level. Then, for example, you would be able to say whether those who were prescribed contraceptive implants had a lower risk of abortion than those who did not use them,” says Furu.

“That’s a big job that would be very time-consuming, but in order to draw any conclusions about the abortion rate, you would need to go about it more thoroughly,” she says.

“We probably disagree a bit on this point,” replies Skjeldestad. “It’s permissible to compare two things that happen at the same time without the data being linked.”

The professor is quite sure they would not have found many abortions had the data on contraceptive implant users and abortions been linked.

“Most of those who have abortions have not used contraception,” says Skjeldestad.

More women should have access to free contraceptives

According to Skjeldestad, the free contraceptive scheme has not been properly evaluated before. The new study looks closely at the numbers, but the users were not interviewed.

Although the scheme has not led to dramatic changes, Skjeldestad believes that it works and could easily be extended to older age groups.

This was also the view of Norway’s Women's Health Committee in 2023, which submitted a proposal for free contraceptives up to the age of 25.

Kari Furu concurs.

“The authorities have gradually increased the age of young women who receive free contraception, and they calculate what it would cost to include more cohorts in the annual state budget process at the Ministry of Health and Care Services,” says Furu.

“We have reduced the number of abortions among teenagers to an extremely low level. Would it help if the 20-24 and 25-29 age groups could also access free long-acting contraceptives? That's something we can't definitively say,” she says.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no