Share your science:

Menstrual capitalism: A lot of people profit from your monthly menstruation

SHARE YOUR SCIENCE: Menstruation presents an endlessly renewed commercial opportunity for period-product manufacturers, who are finding new ways to infiltrate wider markets in an era when taboos are being chipped away. But issues remain that products can’t solve.

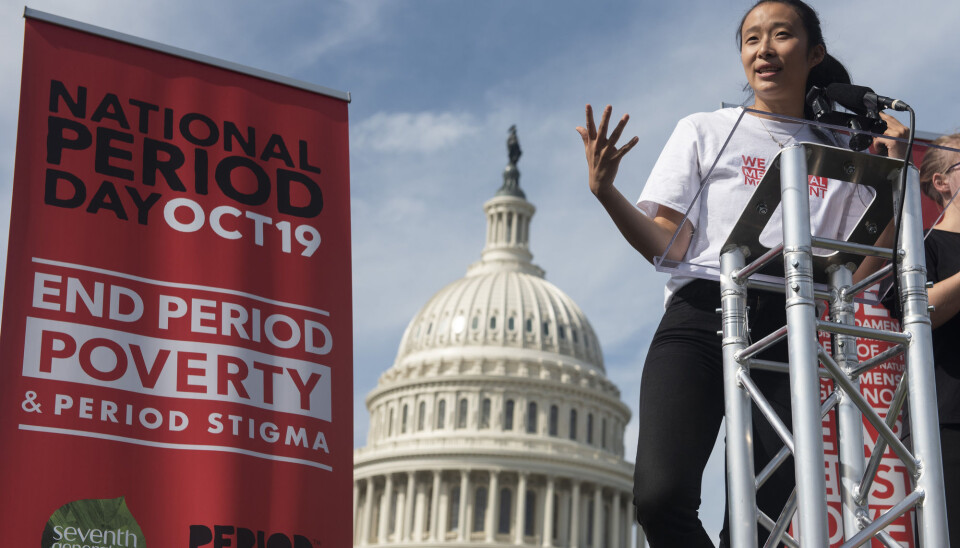

In recent years period activism has hit the global headlines, busting taboos, driving public policy, and prompting companies to create new products. In some countries, including the US, UK, Canada, India and Australia, menstrual equity – the right to equal access to menstrual products and reproductive education, often with a focus on financial issues such as removing the ‘tampon tax’ – has become big news.

However, activists, academics and indeed many people who experience a menstrual cycle are growing increasingly concerned about corporate influence.

While menstruation is a normal event, it has also, in the last 100 years, become a profitable one.

For monetary capital, the monthly occurrence of blood, especially for young people, presents numerous commercial options for cleaning it up, experimenting with hormonal birth control, and trying to make it, as one business recently put it, “cool”.

Let’s talk about menstruation

New types of menstrual products, such as tampons, pads, cups, period pants, vitamins, hormones, teas and foods, and apps to track your cycle, are proliferating as entrepreneurs across the globe are shaking up the market.

A parallel increase is seen in the public interest in the topic. Menstruation is discussed in popular science books and podcasts. Popular culture increasingly depicts menstruation, like for instance the tv-shows ‘Orange is the New Black’, ‘Mad Men’ and more recently ‘I May Destroy You’. In my native country of Norway, the national broadcaster NRK this fall offers its young viewers a show simply called ‘menstruation’ (Mensen).

As images and descriptions of bleeding by artists and writers such as Jen Lewis, Rupi Kaur, and Chella Quint become more mainstream, products aimed at issues other than blood have followed. These include following different skincare routines depending on where you are in your cycle and ‘seed cycling’, which claims that eating specific types of seed before and after ovulation can balance hormones.

Menstruation is everywhere. But while this is mostly a good thing, there is reason for caution. The American lawyer Bridget Crawford, a professor at Pace University in New York, describes what she calls “menstrual capitalism” as:

“the marketing and selling of menstrual hygiene products by means of feminist messages that attempt to create a public-relations ‘halo effect’ for companies that are, at their core, commercial enterprises”.

Menstruating in the “right way”

For people who menstruate or experience contraceptive-induced withdrawal bleeding, commercial products have for decades been a large part of how to handle symptoms and menstrual blood in “the right way”.

In her book ‘Issues of Blood: The Politics of Menstruation’, feminist activist Sophie Laws describes what she calls “menstrual etiquette”. This is a system that means there is nothing to be gained by being noticeably menstruating.

It may perhaps be ok to buy several menstruation-related products, and go to a mensturation themed vernissage. But is it ok to bleed through your clothes? And do these cultural and commercial solutions help those who can barely move due to the monthly pain their menstruation causes them?

Historian of science Sharra Vostral argues that people who are menstruating must go through something akin to a “passing process”, where the goal is to always appear non-menstruating.

The promise that a tampon can solve all menstrual-cycle issues is seductive, but not true. This is apparent for instance through Vostrals research on Toxic Shock Syndrom, TSS.

TSS is a rare but serious condition due to toxic substances that can develop in tampons, and that in its most severe cases can lead to death. Today tampon users are warned against this, but it is less known that it was the company Procter & Gamble and their international competitors who created this situation by developing super absorbing tampons like the brand Rely in the 1980s.

TSS is still somehow present as a warning for the big companies, who today are profiting off a much more positive menstruation debate.

Tackling period poverty

Early on, the industry asserted that once a young consumer was hooked on a product, they would stay loyal. Now that entrepreneurs have entered this hitherto stagnant market, even multinational corporations realise that this might no longer be true.

One issue for many people around the world is the cost of sanitary products. Some governments are moving to mitigate this problem: Scotland, for example, is following in the footsteps of Kenya by introducing a policy to provide free products to combat period poverty. Policymakers in the Scottish government are procuring from many brands, including social enterprises, but multinational corporations also take their share of the investment.

In the United Kingdom, US corporation Procter & Gamble, which manufactures sanitary product brands Tampax and Always, and sanitary-bin provider PHS are on the government appointed Period Poverty Taskforce. This was formed in 2019 after activists succeeded in making politicians take notice of the problem of expensive sanitary products among poor people in the UK, especially children.

The inclusion of these companies in the taskforce has raised important questions: Why are the corporations that in part created period poverty through their pricing models now expected to solve the problem? And what will happen to the other issues that activists campaigned on, such as pain or stigma?

Sold lower-standard products to African countries

In the global south these same corporations have been donating products to women in developing countries for many years, often in collaboration with policymakers. This has been done to combat the assumed ‘backward’ thinking of people who use cloth or natural materials rather than more ‘modern’ disposable products. A goal is to get women to start using products at a young age, as this makes it more likely they will become loyal consumers.

In her book, The Managed Body, Professor Chris Bobel writes about the problems with such colonizing attitudes, and shows how products – both in the north and the south – rarely lead to the automatic freedom that the companies promise. There is a huge contrast between how big multinational corporations relate to consumers in different parts of the world, insinuating that western corporations are better developed to ‘modernise’ the culture of menstruation internationally.

Paradoxically, people in the West are increasingly turning towards reusables at the same time that folks in the global south are told to embrace disposable ‘feminine hygiene’.

But consumers are increasingly critical of this situation. Kenyans for instance, have boldly discussed the technological failure of Western products in the #MyAlwaysExperience scandal, when a number of people found that Always pads caused a rash. Those complaining on Twitter alleged that Procter & Gamble supplied African countries with lower-standard products than those in the West, which they suggested was the reason for the skin irritation. It turned out they were right – the products sold in African countries were of a lower quality than those sold in for instance Norway.

Also, a UK government report on period-related bullying, and the recent death of a Kenyan girl mocked for menstrual stains make it clear that corporate and governmental efforts to solve period shame through products have not worked.

Back to making and washing sanitary pads?

At the same time, 2018 saw the launch in the US of the reusable Tampax Cup, outfitted with disposable Tampax vaginal wipes. This launch followed the success of smaller companies like DivaCup, Mooncup and Lunette who brought the period cup back to the market in the 2010s. The period cup in itself is a much older 19th century invention.

Even if most people still use sanitary pads and tampons (or skip their menstruation due to hormonal contraceptives), the small increase in sales of alternative products was enough to make the big players like P&G give it a go.

Tampax applicator tampons are one of the oldest and most successful commercial menstrual brands in the world, due in part to their disposability and a structure that makes it unnecessary to touch blood. In contrast to this, the Tampax Cup was not a success.

Menstrual cups, in comparison, have a much longer and unsteady history, for the opposite reasons. They rely on a lot of contact with body and blood (something which may not be possible or ok for many), and they can also be expensive.

Consumers in the 1930s, when the first Tampax came on to the market, preferred disposable doses of menstrual protection to the cup’s hands-on insertion. However, the Tampax Cup exemplifies how the traditional industry is responding to the fact that the great-great-grandchildren of their first consumers are changing habits.

Our grandmothers made their own reusable sanitary pads and washed them in between uses. Today a new generation may not look upon this with aversion, they might find it an attractive option. If so, then disposable sanitary pads and tampons have lasted for around a century, as a typical yet not much discussed example of the 20th centuries throwaway culture.

Going beyond the market

In comparison to what corporations offer, the lived experiences of people who bleed (available through #MyAlwaysExperience and #EndPeriodPoverty, for example), reveal a more complicated set of factors.

Consumers are growing restless, and demanding answers to more questions than “How can I keep my underwear clean?” Menstrual pain, heavy bleeding and endometriosis remain pressing issues for many. At the very least consumers would like to know what ingredients their products are actually made of.

The upside to recent corporate interest is that menstruation is being recognised as important, all over the world. The downside is that this recognition is still mostly driven by the wish to sell more products and, so far, seems to mostly benefit those who sell products. When menstruation now increasingly is a topic of public debate, it’s important to remind ourselves of who is talking, and who has something to profit from upholding ideas of menstruation etiquette.

In the UK, Kenya and the rest of the world, activists continue to fight against period poverty and other menstrual issues that cannot be solved by products. Better menstrual care means going beyond what the market alone can deliver.

———

This article is a reworked version of a text first published in the Wellcome Collection.

Read a Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Share your science or have an opinion in the Researchers' zone

The ScienceNorway Researchers' zone consists of opinions, blogs and popular science pieces written by researchers and scientists from or based in Norway.

Want to contribute? Send us an email!