What happened when archaeologists found what could have been the medieval King’s Wharf in the centre of Oslo?

Archaeologists had to destroy nearly all of the medieval ‘King’s Wharf’ soon after they excavated it.

Remains of a massive foundation for a wharf were recently uncovered during excavations in Bjørvika, east of Oslo’s centre. It might have been the King's Wharf during medieval times. But no sooner had the wharf been found than it was gone again.

“Now we have arrived at the most interesting area in our entire excavation and the find that we have been most looking forward to,” says Håvard Hegdal, an archaeologist from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU), in a video about the find.

“And that's what’s been called the King’s Wharf,” he says.

Hegdal is the project manager for one of the last excavations in Bjørvika, an area in what was once a very central part of medieval Oslo — the harbour.

The first parts of the wharf were found during excavations in the 1990s. Core samples from before the current excavation indicated that it would be possible to find a small remnant of the foundation from the wharf even now.

But the archaeologists didn’t find just a little remnant — they found eight metres of intact foundation.

“It’s completely crazy,” Hegdal says in the video.

“The dimensions of the timber here are insane. The logs are twice as thick as any we have found before,” he says.

A straight line from the King’s Estate

The wharf lies in a straight line from the fjord to what was the King’s Estate in Oslo in the 12th and 13th centuries. This is partly why the archaeologists think it may be the King's Wharf.

The wharf was also far below a clear layer of blue clay which originates from a landslide that started in the nearby Alna River. This landslide is dated to the end of the 14th century or the beginning of the 15th century, which means the wharf must have been built long before that.

But this time the archaeologists intend to be absolutely sure.

Samples from the wood have been cut out and sent for dendrochronological examination.

“Then we’ll be able to determine which king built this. It will be quite interesting,” Hegdal says.

They came here from all over the world

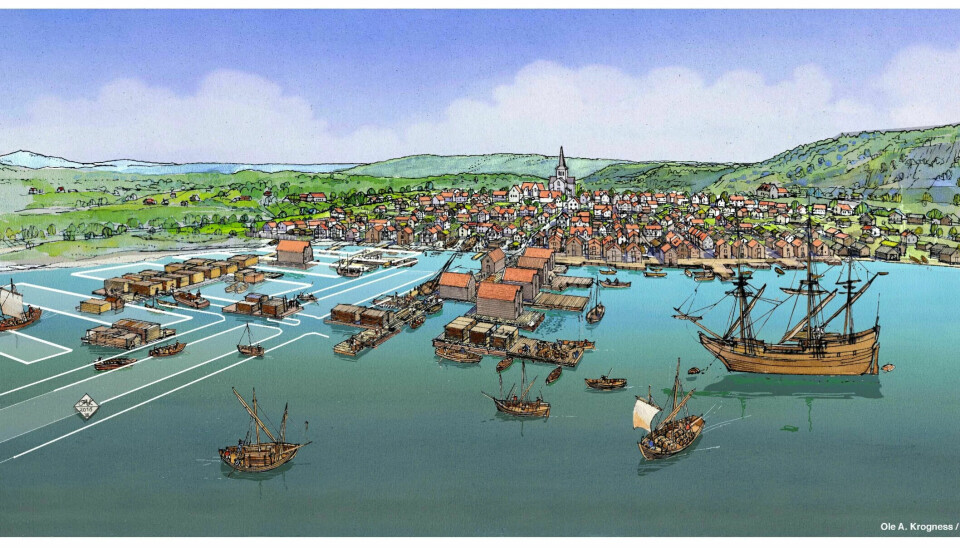

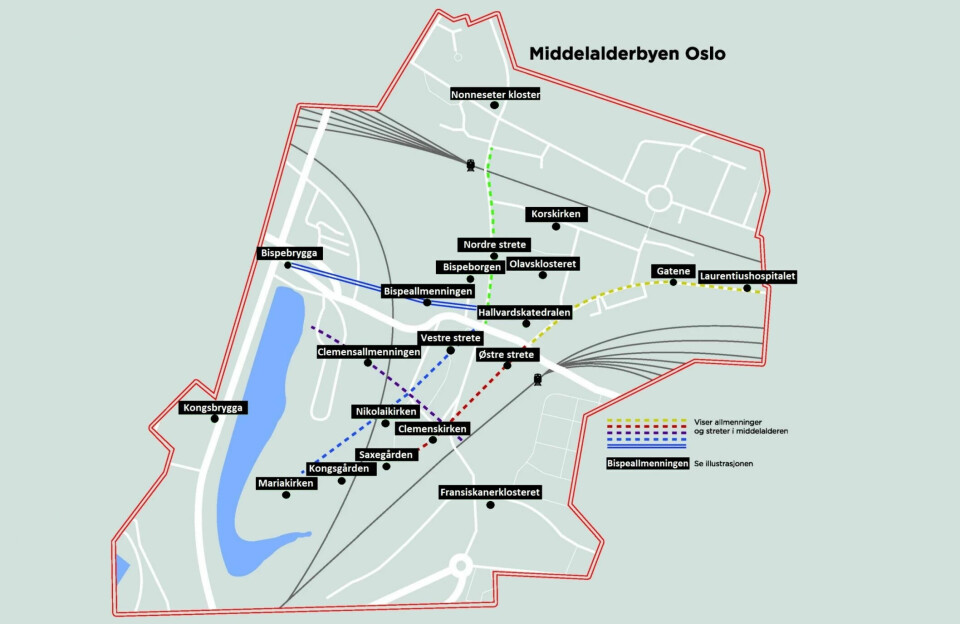

Medieval Oslo at this time had several wharves that provided water access. Several of the roads down to the sea, one called Klemensallmenningen and another called Bispeallmenningen — ended in wharves.

Boats from all over the world entered the harbour city of Oslo right here. They were greeted by the bustle of life on the wharves, which were covered with merchant stalls, warehouses, meeting places and inns.

More than 40 boats dating from the Middle Ages to the 18th century have been excavated in Bjørvika over the last few years. Most are medium-sized boats of ten to twelve metres in length, with some smaller ones of six to seven metres. But archaeologists have also found large anchors of the type that would have been used by much larger ships.

Right on the eve of the excavation, before Easter this year, the NIKU archaeologists found what they believe may be two mooring coffers, for mooring really large boats.

They were found a little further out in the water than the King’s Wharf.

The collection of logs and stones at the right of this photo are the first they found.

A few days later, when they really thought that now there's only clay left, they found another one.

An abundance of mussels around the logs shows that here, the seawater was fresh and fine.

Large logs cannot be preserved

A couple of days after the discovery of the King’s Wharf, it had already been removed.

On NIKU's Facebook page, people asked how they could see it. Project manager Hegdal shakes his head — the wharf foundation is to be destroyed.

First, it was documented, of course. A 3D model can already be found online, while pieces of the logs have been sent for dating.

But the big logs are simply too big. There’s no place to put them, there’s no money to preserve them.

“Wood like this has to be immersed in water in containers. Preserving logs like that costs a lot,” Hegdal says to sciencenorway.no.

Besides, he has to move quickly.

“We take samples from all of the timber, but then we have to get it out of the way, so we don't delay the construction process,” he said.

Isn't that unfortunate? To find a large, well-preserved section of a medieval royal wharf, and to then just get rid of it?

“It's not great,” Hegdal allows.

“We have unearthed an endless amount of fine things here, not only the King’s Wharf, but also lots of magnificent objects. Oslo should have a separate medieval museum to showcase all of this,” he says.

One corner in, another corner out

As a rule, all the large wooden structures that the archaeologists find have to be disposed of, Hegdal says to sciencenorway.no a few weeks later on the phone.

The whole wharf was destined for the rubbish heap, like so many other great wooden structures from the Middle Ages that archaeologists have unearthed in Oslo in recent years.

But the archaeologists couldn't bear to throw away the entire wharf.

“We had to do a little horse-trading with the Museum of Cultural History,” Hegdal says.

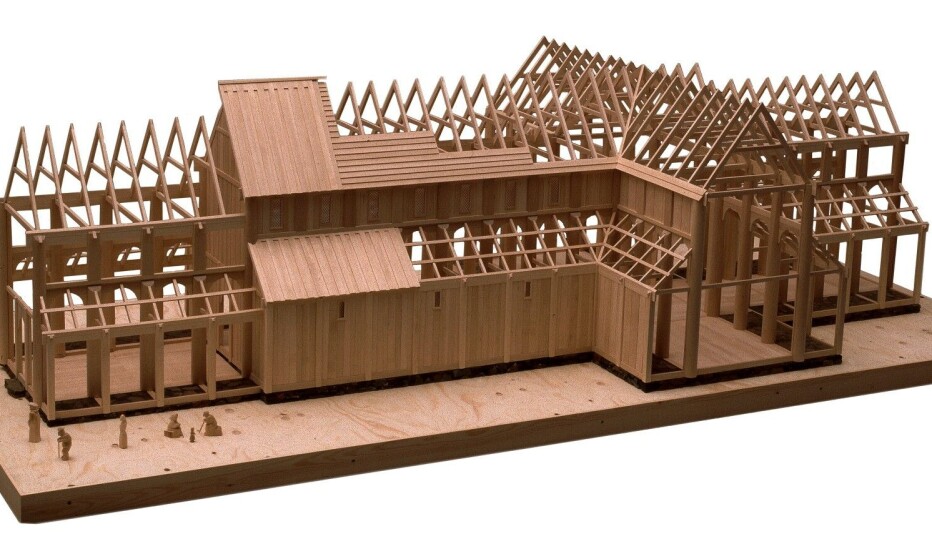

A corner of one bulwark, the square boxes that make up the foundation, was cut off, hoisted out and immersed in water in a container.

A corner of a bulwark from the 15th century had to be disposed of, so that this new corner could be kept.

“This is clearly much more valuable, so it was a fair trade-off,” Hegdal says.

“A small piece of the high medieval wharf system has now been preserved, with several very interesting construction details,” he said.

Bryggen in Oslo?

Oslo should have something like the famous UNESCO World Heritage site in Bergen called Bryggen, Hegdal says. At one time, there was talk of a medieval museum in the old locomotive workshop in the Medieval Park in Oslo, according to the archaeologist. This was when the possible relocation of the Viking ships was under discussion, in the early 2010s.

That story ended with the decision that the collections were too vulnerable to be moved. Instead, the ships will finally, after many years of battles, get a new home in a museum which is currently being built around the existing Viking Ship Museum.

In the meantime, Oslo has undergone extensive archaeological excavations, perhaps the most comprehensive in recent times, according to Liberal party politician and former Minister of Justice Odd Einar Dørum. He is chairman of an association called Medieval Oslo (link in Norwegian).

A lot of good things have happened, Dørum says. To think that these excavations have even taken place!

But then at the last stage, we’re let down, the experienced politician claims. Because where does everything the archaeologists find end up? If it’s too large and complicated to preserve, like the King’s Wharf, it’s destroyed. Objects that are preserved, end up in a warehouse in the outskirts of Oslo.

Here, in a large tank filled with water, lies, among other things, a piece of one of Oslo’s medieval wooden streets. Bispeallmenningen was also destined for the rubbish heap. Political action put an end to that.

The timbers that made up Bispeallmenningen were excavated in 2018. They are dated to the 13th or 14th century.

The logs were the substrate, with twigs and birchbark on top to prevent the street from becoming excessively muddy.

The plan was for this entire find to be destroyed. But political action ensured that 12 logs were preserved in water tanks in the Museum of Cultural History’s storage magazine.

Three metres of medieval street

In 2018, archaeologists found 37 metres of what was Oslo's main thoroughfare 800 years ago, Bispeallmenningen.

The excavations took place in connection with the development of Follobanen, a 22-km long express train line between Oslo and the town of Ski. The plan was for the old logs to be destroyed after they were sampled, but the National Trust of Norway, the Oslo Cultural Heritage Management Office and eventually a whole bunch of politicians got involved and thought this was unacceptable.

Around three metres of the street’s surface, a total of 12 logs, was eventually preserved. The cost of conserving them in 2018 was an estimated NOK 4.2 million, says Isa Trøim, head of archaeology at the Norwegian Directorate of Cultural Heritage. Trøim said that there are ‘several initiatives underway to find a solution for what to do with the logs.’

“It was a spontaneous uprising,” says Dørum, who himself took part in what he calls a rescue operation.

“Many people in the political world woke up at the same time, which eventually led to a minister taking the initiative to preserve part of the wooden street,” he said.

Extensive excavations seeking cultural policy

The wooden logs from Bispeallmenningen — some of them, at least — were thus saved from destruction. But how long will they stay in a water tank in a warehouse on the outskirts of Oslo?

“We are facing a desperate situation,” Dørum says. “There’s no storage space, and there’s no exhibition space.”

Dørum and the Medieval Oslo association also dream of a medieval museum in Oslo, for example in the locomotive workshop in the Medieval Park. But there are some cultural policy gaps here, Dørum believes.

The developers pay for archaeological excavations. The archaeologists find lots of wonderful objects and gather new knowledge about Oslo's history. Then nothing else happens.

“The archaeologists' efforts produce more than what there is political will to do something about,” says Dørum.

“The Viking ships are wonderful, but the Middle Ages don't get the attention they should. People have not understood enough of this period’s importance for Norwegian history, the knowledge we have in laws and legal sources, and the richness of the contact between Norway's medieval cities and the outside world,” he says.

So should the King’s Wharf have been preserved in its entirety?

“It’s great that the archaeologists managed to preserve some of it. But I think it is worrisome and sad that most of it is being destroyed. It shows us very clearly that the oldest Oslo was a port city. Should this physical cultural heritage be thrown away because we lack storage space and enough exhibition space, is it sustainable?” he asks.

“How will posterity view us because we did not have better opportunities than what is possible now?”

Quite a lot is discarded

NIKU's job is to carry out the archaeological excavations. The finds that are to be preserved are then sent to the Museum of Cultural History (KHM).

Archaeologist Jan Bill is the project manager for KHM's investigations of ships in the excavation where the King’s Wharf was found.

“We don’t preserve everything we find simply because not everything has the same value in terms of dissemination and sharing of information, and we cannot preserve them without concrete plans of public exhibition,” Bill says.

“The builder has to pay the expenses for the excavation, and we can’t justify saving everything. Our task is to ensure that we protect the potential knowledge that we can glean from the archaeological finds,” he says.

This means that if something is to be destroyed it must first be documented. Pictures and video are taken, 3D models are made, and sample material is taken out. The documentation must ensure that what has been found can be studied by researchers in the future, even if the object itself has ended up on the rubbish heap.

Large wooden objects are particularly difficult and expensive to preserve.

“Just look at how much we have invested in the Viking ships to secure them for the future,” Bill says.

“So today, quite a lot is in fact discarded because the assessment is that the value of physical exhibit does not justify the price we would have to pay in order to keep something in our collection for the foreseeable future,” he says.

A correct decision

Bill believes that the decision to discard most of the King’s Wharf was correct. It has even been done once before, he points out, in the 1990s when the first remains were found.

“I am very fond of wood and have no difficulty in finding this exciting,” Bill said.

“But from a scientific point of view, I would like to think that here, this is a structure made of logs, they are lashed together, and the construction is not very complex. I know that with the documentation and the tests that have been taken, the potential knowledge we can gain is secured. We don't lose anything in that context,” he ensures.

Apart from the physical possibility of actually seeing and experiencing it, of course.

“But how many people should we expect to want to come and see this bulwark? And is that enough to justify the investments that must be made to preserve, store and exhibit it?”

Bill believes that the road from excavation to exhibition is quite short in Norway and that Oslo has several good museums that showcase the city and the Middle Ages, such as the City Museum and the Museum of Cultural History.

“I could easily imagine a nice medieval museum in the Medieval Park, it would lift the whole area. It is not difficult to say yes to something, it is more difficult to say what we should not spend money on. If I have to choose between a medieval museum and spending money on a Viking Age Museum, I’d choose the Viking Age Museum. There’s nothing bad about the Norwegian Middle Ages, but Norway was much less central then, from an international perspective,” he says.

Bonus round from the 12th century

The Bjørvika excavation was completed just before Easter.

When the first mooring coffer appeared, the archaeologists really thought they were pretty much done.

“It was an insane bonus round of this excavation,” said NIKU’s Hegdal. “This is completely different from anything we have seen before.”

A few days later, another mooring coffer appeared, nine metres away from the first one. Perhaps they were once connected by a wharf over the water?

“It’s a fantastic end to the excavation, completely unique to find something like this and totally unexpected from what we started with,” Hegdal says enthusiastically in another video from the excavation. “Now every little piece must be dated!”

The mooring coffers lay deep below the landslide layer from the end of the 14th century and were clearly much older than the King's Wharf front from the High Middle Ages. Hegdal says they are unsure how old they are — they may even be as old as the 12th century and thus the oldest find dated in Oslo.

Could have kept it, had to toss it

The apartment buildings are growing next to the excavation site. Soon they will lose their view on one side when also the plot that was once a busy harbour with a royal wharf is transformed into new homes in old Oslo.

Several decades of excavations have provided completely new knowledge about Oslo's past history, the archaeologists at NIKU say.

A corner of the King’s Wharf has now been preserved. A political action saved 12 logs from the medieval street Bispeallmenningen in 2018. But this was really quite random, says Hegdal.

“Those logs were poorly preserved and actually quite shabby,” he says.

"Suddenly, the whole issue was in the media, there was a lot of fuss. But compared to other things we've dug up and discarded, which have been much better preserved, these were rather dismal,” he says.

Archaeology is necessarily about destroying things, Hegdal points out. Things are dug up and moved from where they once lay.

“But I feel that there is a lot of potential information and experiences that could have been shared with the public that is lost from the structures that we have dug up over the years," he says.

"More of the Middle Ages will be on display at the new Viking Ship Museum. But during the past years, as we have excavated these large structures, it hasn’t been possible to preserve them. This is when we've excavated them, and then we've just had to destroy them.”

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no