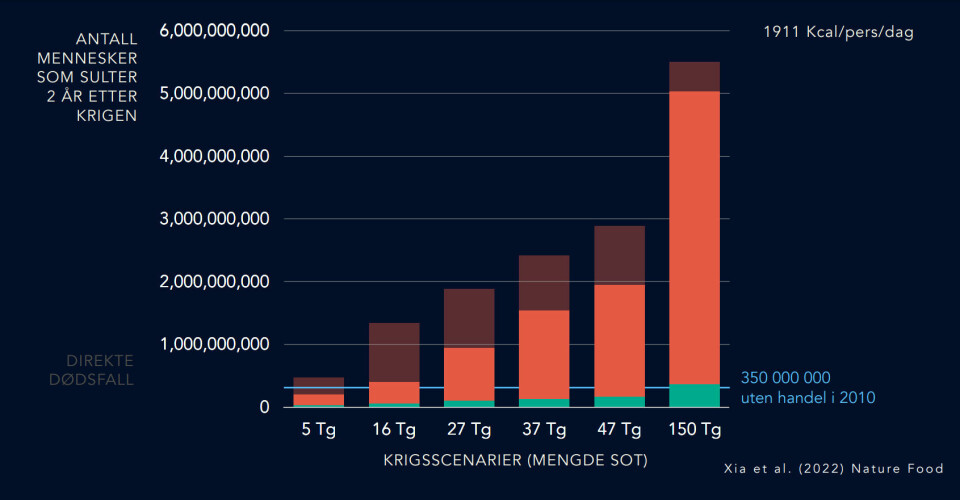

Even a limited nuclear war could cause billions to die of starvation

Soot in the atmosphere will cool the climate dramatically. The resulting failure in food production and trade will cause many people to starve, researchers say.

A war in which countries use nuclear weapons to reduce each other's cities to rubble would be unthinkably awful. The bombs themselves would annihilate an incredible number of people.

But a war of this nature could also result in apocalyptic conditions across the globe.

If two per cent of the world's nuclear weapons were to be fired in densely populated areas, it would result in a global cooling.

Two billion people would probably die of starvation.

Kim Scherrer is a postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Bergen. She was involved in making these grim calculations.

She says a blanket of soot in the atmosphere would wreak havoc with the climate and food supply.

100 to 4,400 bombs

The consequences of a nuclear war have been the subject of a number of studies in recent years.

Scherrer was involved in a study published in Nature Food last year that looked at this problem. Scherrer has also studied the effects of a nuclear war on the ocean.

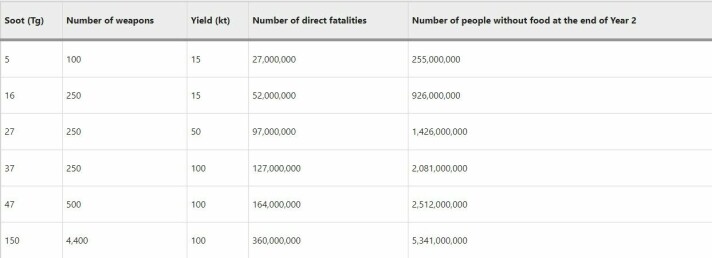

The Nature Food study looked at six war scenarios.

The first scenario involved a hypothetical nuclear war between India and Pakistan. Here, the researchers assumed the countries would lob 100 nuclear weapons at each other, each the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

In subsequent scenarios, the researchers increased the number of bombs to 250, so that the explosive effect would be greater. Nevertheless, even 250 bombs represent only a small percentage of the approximately 12,500 nuclear weapons that exist.

The worst-case scenario that the researchers considered was a true doomsday situation, in which the USA and Russia, as well as other countries that are drawn into the conflict, fire a total of 4,400 weapons at each other. This represents slightly less than half of all weapons stockpiled by the USA and Russia.

Firestorm

Since the Cold War, it has been hypothesized that a nuclear war could result in a climate catastrophe. Today, researchers can test this hypothesis using advanced Earth system models, which simulate the climate.

Scherrer explains why a nuclear war would create global cooling.

“If you use nuclear weapons in cities or densely populated areas, the result can be enormous fires. We saw that in Hiroshima,” she said. “These weapons are so powerful and it gets so hot that you set fire to almost everything in the city.”

Scientists call this a firestorm. The air above the fires rises and is fed by oxygen coming in from the sides.

Smoke and soot from the fires rise into the atmosphere. The smoke and soot rise so high that they aren’t cleaned out of the atmosphere by rain and can remain aloft for several years. The soot spreads throughout the atmosphere and darkens the earth.

Between 1.5 and 10 degrees colder

In the least damaging war scenario, this layer of soot and smoke block five per cent of the sunlight. The most catastrophic scenario would lead to as much as 70 per cent of sunlight being blocked from reaching the Earth's surface.

“It would basically get darker everywhere,” Scherrer said.

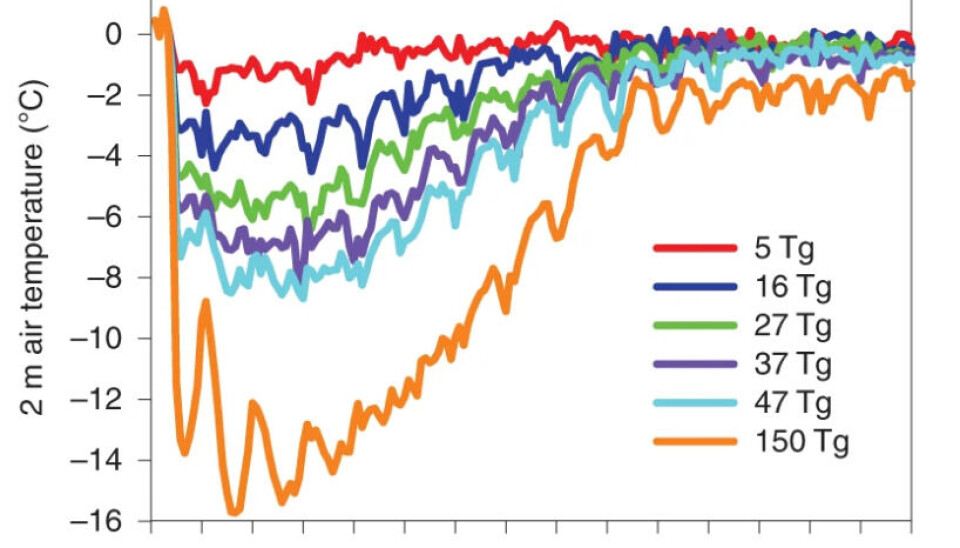

Without sunlight, the Earth will chill dramatically. The global average temperature would fall by between 1.5 and 10 degrees Celsius, depending on the scenario.

In comparison, it was 7 degrees C colder on average during the last ice age maximum than today.

The effect would be greater on land than over the ocean. It takes longer to cool the ocean.

The temperature over agricultural areas would drop dramatically. In the third scenario, where 250 bombs were dropped, the temperature in agricultural areas would drop by five to six degrees for several years.

The graph shows how much the temperature will drop in agricultural areas under the different scenarios.

A hazy sky

Soot in the atmosphere will also affect how much it rains. In general, it would rain less in most areas, while some areas would receive more rain.

Globally, the drop in precipitation would be 8 per cent in the least-bad scenario and 60 per cent in the worst-case scenario, Scherrer said.

What would the aftermath of a nuclear war be like in Norway? Would it be something different?

Two historical volcanic eruptions, Tambora in 1815 and Krakatoa in 1883, provide a clue.

The Tambora eruption led to cooling in Europe. The year after the eruption was called "the year without summer".

“There are a number of descriptions in literature and in art that it was cold, and that winters were extra cold. Even though it was summertime, it never really was like summer. Some paintings from this period show that the sky is a bit hazy,” she said.

Edvard Munch's "Scream", for example, was painted a few years after the Krakatoa eruption, Scherrer said.

One theory is that Munch was inspired by a red sky that was the result of the volcanic eruption. There were more particles in the atmosphere than usual, which created red skies.

Serious for Norway

In the worst-case scenario, sunlight would be reduced by 70 per cent in Norway, Scherrer said. The country would be very dark.

“Here we have nothing we can compare this to, to help us understand what that would be like,” she said.

Climate effects under all scenarios would hit Norway hard.

“Norway is in a unfortunate location; it’s cold here, with a short growing season. So here and in other northern countries, agriculture will be substantially affected,” she said.

It’s easy to imagine that grain would not ripen properly, that there wouldn’t be enough grass for livestock, and that vegetables could freeze in the fields. The impact of the nuclear war would last for several years.

The researchers calculated the reduction in food production using a global crop model that simulates how crops and grass grow under different climate conditions.

The results show that agricultural production in Norway would fall by around 40 per cent under the least damaging scenario.

In the worst-case scenario, production would drop by 80 per cent, Scherrer said.

Hunger

The model shows that between one million and 4.5 million Norwegians would die from starvation.

The figures depend on the scenario, international trade, whether people continue to keep livestock and whether people stop wasting food. But there are no situations where things go well for Norway.

“It is possible that you could adapt in different ways and try to grow crops that are different than what we grow today. But it usually takes time to adapt,” Scherrer said.

Many countries would see a drastic drop in food production. Thus, it is not unlikely that countries would impose export restrictions to protect their own populations.

11 to 90 per cent less food

Under all scenarios, global food production would fall.

The greatest drop in worldwide food production in modern times was just five per cent, Scherrer.

In the scenario where the least amount of soot is released, production would fall by eleven per cent, but for five years. This would drive prices up, and countries may decide to stop exporting food to protect themselves.

In the second worst scenario, the supply of calories would be reduced by 50 per cent and in the worst case by 90 per cent.

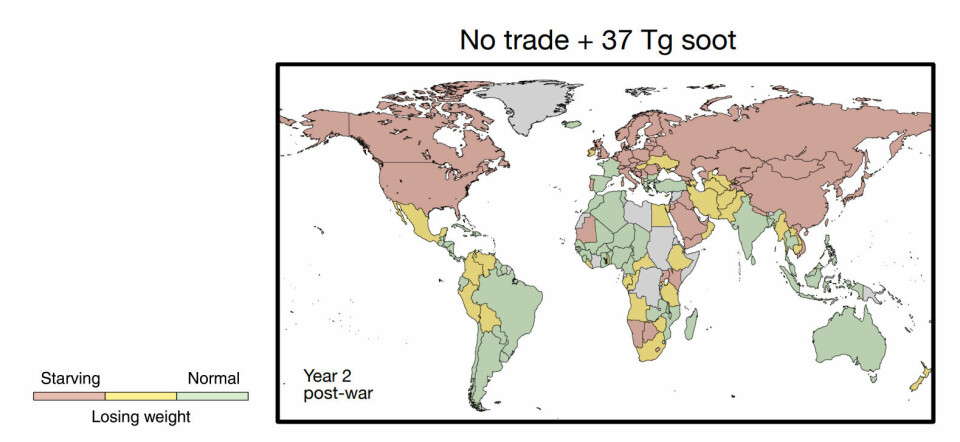

Not surprisingly, this will have major consequences. The map below shows which countries will lack food in scenario number 4 (37 Tg). Red countries are where people will die of hunger, yellow countries are where people will lose weight. Countries in the northern hemisphere will be particularly affected.

Up to several billions dead

The consequences of different nuclear war scenarios range from an unusually strong shock to worldwide food availability, to a global famine, Scherrer said.

Between 500 million and 5.5 billion people would die of starvation in a situation where global food trade has been halted.

If people stop wasting food and eat all the grain that now goes to animal feed, the picture improves somewhat. But there would still between 200 million and 5 billion deaths.

Made an impression

If food trade continues and societies adjust to eat both animal feed and food that was previously wasted, it is theoretically possible that there would be enough food in most scenarios.

That also assumes that everyone eats just the minimum of what they need and that the food is shared equally between everyone in the world, which is not the case today.

Kim Scherrer says it's disturbing to see what came out of the models they made.

Even if, in theory, you could manage to get enough calories for most people in the least damaging scenarios, it would still be an extreme shock to the system, she says.

“We have seen it now. The coronavirus and Russia's invasion of Ukraine have had a major effect on people's access to food around the world. Food has become more expensive, and people have had less access to food,” she said.

An eleven per cent reduction in food production over five years, as predicted by the least damaging scenario, would be much, much more of a shock.

“I think this would have substantial consequences for the entire system. And our simulations also didn’t take into account whether there would be a shortage of fuel, artificial fertilizer, herbicides, fungicides and insecticides and everything else you need for large-scale agriculture,” she said.

Many nuclear weapons

What was most apparent, Scherrer said, is how dangerous it is for there to be so many nuclear weapons in the world today.

“Although the use of 100 weapons sounds like a lot, it’s less than one per cent of the weapons out there,” she said.

The simulations also made it very clear how the use of more of the weapons in the world’s arsenals can grossly magnify the consequences, Scherrer said.

The findings have previously been reported by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) (link in Norwegian). Kjølv Egeland conducts research on nuclear weapons security at the University of Sciences Po in France and commented on the study.

“The most important thing here is that we take this research seriously. The study makes a number of assumptions, but the same general findings have been made by so many different research groups that it is difficult to escape how serious they are,” he told NRK.

The models used in the research are the best society has for simulating effects on the climate after a nuclear war, he said.

Uncertain estimates

Steinar Høibråten at the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI) has previously commented on the study from Nature Food in an article from the Norwegian News Agency (NTB).

He pointed out that studies like this make a number of assumptions, which makes for uncertainties in the estimates of the number of deaths.

“It depends on what the weapons hit, how big the fires are and how much swirls up in the atmosphere,” he said.

If the weapons are used against military bases, and to a lesser extent against cities, the number of dead would probably be much lower. Wind conditions and how high in the atmosphere the bombs are detonated would also play a role.

Reference:

Lili Xia, et al.: "Global food insecurity and famine from reduced crop, marine fishery and livestock production due to climate disruption from nuclear war soot injection", Nature Food, 15 August 2022.

------

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version on forskning.no