Here’s why children and young people should take iodine in the event of a nuclear accident

But it will hardly be needed in the event of a nuclear accident in the Ukraine, says Ingrid Dypvik Landmark, from the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority.

A nuclear accident can release many different radioactive substances to the air.

We can protect ourselves from one of these substances by taking iodine tablets. The substance is radioactive iodine, more specifically the isotope iodine-131.

If we inhale radioactive iodine or ingest drinks or food that have been contaminated with the substance, it can be absorbed by our thyroid gland.

This is especially true for children, breastfeeding and pregnant women.

“Children have a more active thyroid gland. That’s why it’s most important for the very youngest to take iodine tablets, and then the urgency decreases with increasing age,” said Ingrid Dypvik Landmark, a senior adviser at the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority, to sciencenorway.no.

Iodine is important for metabolism

But why does this radioactive substance end up in this particular gland?

To explain this, you first have to understand the role of natural iodine in the body. Humans need this mineral for their metabolism to work.

The stable version, iodine-127, comes from foods such as milk, white fish and salt.

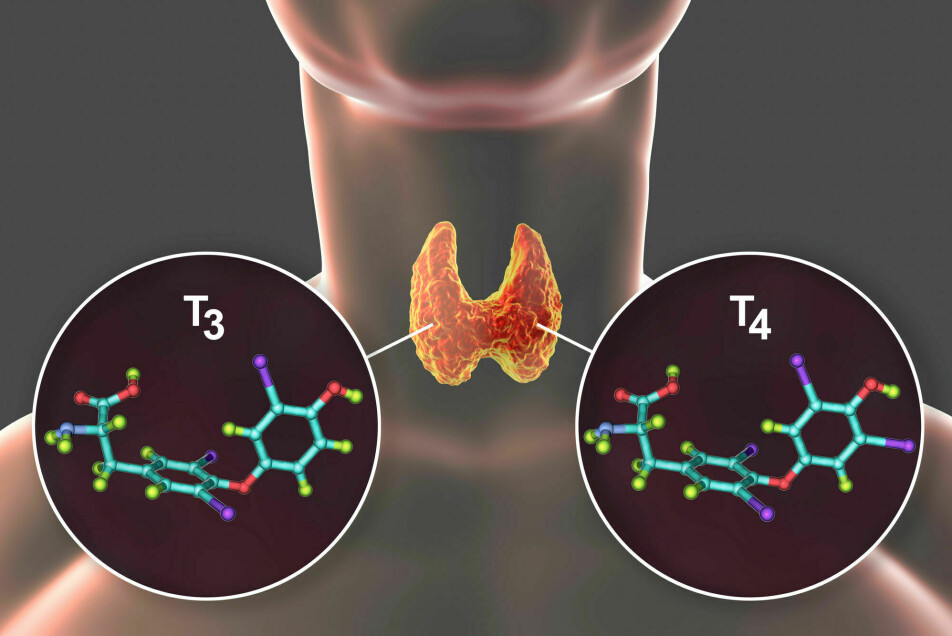

The thyroid gland is located in front of the neck, below the larynx. This organ is the one that particularly needs iodine. The gland makes two hormones that speed up the metabolism. And iodine is one of the building blocks for these hormones.

That’s why it makes sense that children and young people are particularly vulnerable. Their metabolism is in high gear, since they are growing and developing.

In other words, the gland absorbs iodine to make enough metabolic hormones.

Stable iodine saturates the thyroid

In the event of a nuclear accident or a nuclear attack, the need for iodine can present problems.

If there is a lot of radioactive iodine in the air or in food, the radioactive variant will be absorbed by the thyroid gland.

“Radioactive iodine will stay in the thyroid and release radiation, which can lead to cancer in people under 40. This is especially true for children,” says Landmark.

After the unstable iodine has ended up in the gland at the bottom of the neck, it emits radioactive radiation that damages the nearby tissue.

But iodine tablets can protect people in the event of a nuclear accident. The pills contain such large doses of stable iodine that the gland is completely saturated.

For the next 24 hours, it will not absorb any more iodine.

Probably won’t need iodine if there is a release in Ukraine

There is really nothing special about iodine in these tablets, which were quickly sold out in Norwegian pharmacies after the war in Ukraine started.

The mineral itself is exactly the same as in iodine supplements.

But the dose is more than 600 times higher, Landmark points out. Therefore, there is little point in taking supplements to protect against radioactivity.

Should there be a nuclear accident in Ukraine, we can probably leave the pills in the medicine cabinet anyway.

“It will most likely be unnecessary to take iodine tablets. Even with a large release and wind in our direction, it will take 48 hours before it gets here. By that time it will be diluted and there will be less radioactivity,” says Landmark.

Rare side effects of the tablets

The Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority still wants people to have the tablets in our home.

There are nuclear power plants that are much closer to us, such as in Sweden. And nuclear submarines along the coast can also be a danger.

At the same time, the recommendation only applies to people under 40 years of age. But can’t people who are over 40 take a tablet just to be on the safe side?

“There’s no point. Especially for people over 60, the risk of side effects will be greater than the benefit,” says Landmark.

Iodine tablets generally have few side effects, but in rare cases, people have had metabolic disorders.

Therefore, it is also important to wait to take the tablets until the authorities have recommended it.

Not sure if adults can get cancer from radioactive iodine

After the Chernobyl accident, researchers failed to find clear answers as to whether adults in the surrounding areas got thyroid cancer from radioactive iodine.

Some studies have suggested that they may have had a doubling of the risk of getting this type of cancer, according to a 2006 study summary in the journal Endocrine Pathology.

But since the disease is so rare, it is difficult to know for sure.

No pill to protect against other radioactive substances

So what about all the other radioactive substances that end up in the air after a nuclear accident?

When one of the reactors at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine exploded in 1986, hundreds of different radioactive substances filled the air.

So why aren’t there pills to protect us from all these other substances?

“They simply do not exist,” says Landmark. Therefore, the most important recommendation is to stay indoors after a nuclear accident or a nuclear attack.

In addition, many radioactive substances have such a short half-life that they became harmless after 24 hours. These will only be dangerous for those closest to the accident.

4,000 children got cancer in the surrounding areas

Some of the rescue workers present after the Chernobyl accident died from large radiation doses.

But in the long run, iodine-131 actually seems to have created the most health problems.

Researchers estimate that 4,000 children in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia contracted thyroid cancer due to this radioactive isotope.

Most survived, but many struggle with side effects and have to take the metabolic hormone thyroxine in tablet form for the rest of their lives, according to an article in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association from 2007.

Radioactive caesium led to slaughter

In Norway, on the other hand, neither the authorities nor researchers recorded an increase in this type of cancer after the Chernobyl accident.

Radioactive caesium created more trouble in Norway.

The isotope fell to the ground in Norway and ended up in the soil. Since it has a half-life of 30 years, it takes a long time to disappear.

Immediately after the nuclear accident in 1986, many thousands of grazing animals had to be slaughtered and were inedible, because they had ingested too much radioactivity.

Special feed still used to remove radioactivity

Levels are now considerably lower in Norwegian soil. But in some places in the country, such as in Valdres and Trøndelag, there can still be quite a lot of radioactivity in plants and animals. Especially in mushrooms.

No additional cancers have been detected due to caesium levels in Norway. And people eat so few mushrooms that there is nothing to worry about.

For sheep and reindeer that eat large amounts of fungi and other wild plants, however, radioactive caesium can accumulate in their bodies.

Therefore, the Norwegian Food Safety Authority regularly recommends that the animals be fed a special food for a period before they are slaughtered, especially in years when there are many mushrooms.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no