Researchers uncover insider trading on the Oslo Stock Exchange

Insider trading by a group of executives below the top tier has been flying under the radar, according to researchers. The execs have been making significantly higher profits on buying and selling shares in their own company.

Insider trading in stocks is primarily associated with the top executives in large limited companies.

These primary insiders are required by Norwegian law to promptly publish the shares they buy and sell in their own company. The same goes for their immediate family members and the company’s board members.

This insider trading is completely legal, provided the public can find out about it within the required notification timeframe.

A new study, however, reveals that this is not the group of employees in large companies that are raking in profits based on the inside knowledge they have.

The employees who are clearly profiting the most from insider knowledge of their own company – and trading stocks in the company – are the executives who sit just a little below the top managers, according to the study.

The execs under the top executives

The companies themselves usually identify the company’s primary insiders.

Typically, a top executive reports trades in his own company as soon as he has made them – and is thus acting completely legally, since everyone else can then immediately see what the top executive possibly knows and can use this knowledge to buy or sell their own shares.

But below the top tier are other executives who are not listed as primary insiders with the financial authorities.

They are therefore not required to publish their trading transactions in their own company.

These employees fly under the radar of The Financial Supervisory Authority of Norway's supervision of insider trading on the Oslo Stock Exchange. They also remain out of sight of everyone else in the stock market who closely follows insider trading at the Stock Exchange.

Extra high returns

Economics professor Hans K. Hvide at the University of Bergen and professor of finance Kasper Meisner Nielsen at Copenhagen Business School are behind the new study. They found that this previously unknown group of insiders earn particularly high returns on their investments in their own limited company.

The extra profit they reap from their own-company investments corresponds to an average of more than 1 per cent (100 basis points on the Stock Exchange) per month, the researchers found.

This return for purchases and sales is clearly higher than what the top bosses achieve when they do legal insider trading.

Not especially skilled with stocks

Just to be sure, Hvide and Nielsen checked whether people who work a little below the top management level in large companies might just be especially talented at buying and selling shares.

They did not find this to be the case.

The researchers observed that returns achieved on buying and selling shares from other companies by this same group of investors on the Oslo Stock Exchange were no better than the average returns of other investors.

International attention

Hvide and Nielsen have written an article about the study that they conducted, but it has not yet been published in any scientific journal.

The two researchers believe the method used in their study is quite unique.

They think that if similar studies are carried out at stock exchanges in other countries, the results there would be similar to what the researchers observed at the Oslo Stock Exchange.

“Our study addresses an issue that is relevant in a number of places in the world: What information do 'second-tier' executives have for own-company inside trading that enables them to achieve better returns on stock trading at the expense of others?”

Research has taken a long time

“I think we’ve been working on this study for seven years now,” says Hvide.

In order to make this discovery, the researchers needed huge amounts of trading data from the Oslo Stock Exchange.

Hvide says that progress has been slow, in part because the researchers at one point realized that they did not yet have enough data to base their study on.

“So then it was just a matter of sitting down and waiting until a few more years had passed,” said Hvide.

Known insider trading not very profitable

A good deal of research has been done on insider trading in the stock market in Norway and other countries. However, most of this research has looked at the legal trading done by publicly known primary insiders.

The results of this research has often been rather surprising – and contrast with what Hvide and Nielsen have found.

“Other research has largely concluded that the trades reported by primary insiders to the Oslo Stock Exchange have not yielded significantly greater returns than other trading,” says Hvide.

Completely legal insider trading by top executives and board members in Norway has thus not proved to be particularly profitable relative to other share trading on the Oslo Stock Exchange.

Hvide highlights a previous study by Professor Espen Eckbo at NHH Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen, in which Eckbo collaborated with Professor Bernt Arne Ødegaard at the University of Stavanger.

“Eckbo's argument was that if there was one place we would expect to find a so-called ‘insider’s market,’ it would be in Norway since it’s a small community,” says Hvide.

“But he and Ødegaard didn’t find any higher returns among insiders here in Norway than researchers have found in other countries.”

Could Oslo Stock Exchange still be an insider’s exchange?

“Our new study looks at this differently,” Hvide says.

“Looking at an entire data set – the entire stock market – provides a completely different picture. That’s what we’ve done in this study.”

Hvide and Nielsen do not know whether the Oslo Stock Exchange has more insider trading than other stock markets in the world.

They wonder if their discovery at the Oslo Stock Exchange could prove similar to what researchers might find in other countries, given the possibility to look at equally large own-company trading datasets made by insider traders flying under the radar.

In Norway, illegal insider trading can be punished with imprisonment for up to six years, but few examples exist of such severe judgments.

Insiders who fly under the radar

The new study by Hvide and Nielsen thus paints a completely different and gloomier picture of insider trading than what Eckbo and Ødegaard found.

Instead of using the reports by the registered primary insiders about what shares they buy and sell as their starting point, the two researchers have put the spotlight on what they call executives below the radar.

A company’s operations director is an example of this kind of employee.

Enormous dataset

“This group, which isn’t listed as being primary insiders, is seeing solidly greater returns,” Hvide says.

Hvide and Nielsen – through analysing an enormous data set consisting of all stock trading conducted on the Oslo Stock Exchange over many years – were able to paint a new picture of the hidden insider trading on the Exchange.

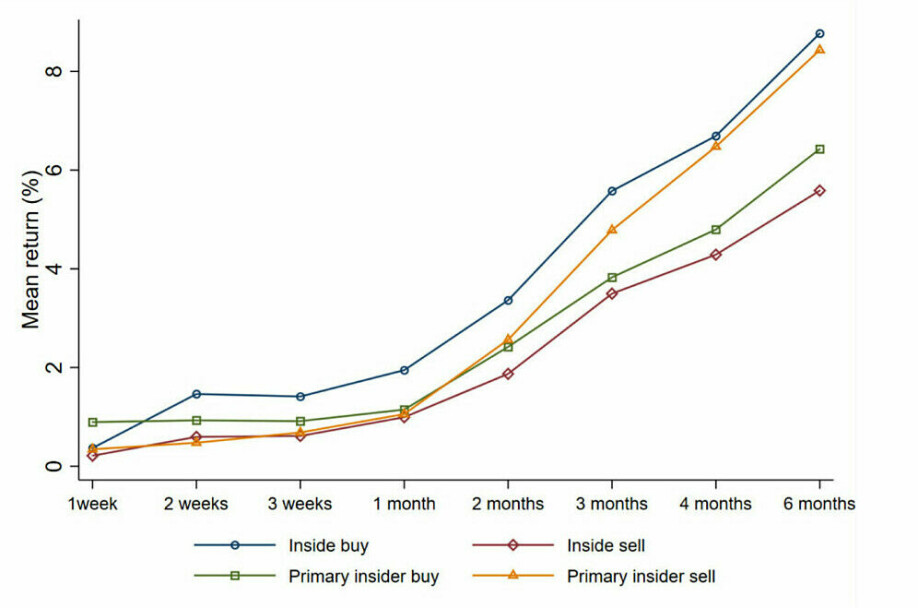

Their findings are shown in the graph below.

- The blue line at the top shows the average return for insiders who trade in their own company – and who fly under the radar of the financial authorities' supervision and the attention of others.

- The green line shows the average return to known primary insiders – the top executives and board members who have to report their trades publicly.

Hvide and Nielsen’s study shows that primary insiders do not achieve unusually high returns when they trade in the company's own shares. This aligns with what Eckbo, Ødegaard and other researchers have found previously.

“But in the graph you can also see that the executives flying below the radar achieve distinctly better returns than primary insiders do,” says Hvide.

Not yet peer-reviewed

Hvide believes that the new method utilized in this study could be used to reveal more insider dealings than the ones the researchers found here.

The method could be used to find trades made by family members that have not been reported, for example.

“Up to now no one could see what we’re now able to detect using our new method,” he says.

Hvide also emphasizes that the study that he and Nielsen have done has not yet been peer-reviewed. That is, it has not yet been critically examined by colleagues looking for errors or omissions in the study.

Do insiders use their information?

Commenting on Hvide and Nielsen's research findings, Eckbo says the most important - and most difficult – part of the discussion about insider transactions is whether the insiders actually use their insider information when they trade. Most often what’s shown is what happens to the company's portfolio over a fixed period, typically a month, after an insider purchase, as is also reflected in Hvide and Nielsen’s study.

“But insiders normally don’t achieve the same level of return as the company over the next month because they tend to hold onto their stocks for much longer,” he says.

Eckbo and Ødegaard have instead estimated the insiders’ actual realized gains by using the actual period the share is held.

“This is strictly necessary if you’re asking whether insiders are buying low and selling high – and not whether the company does well the following month,” Eckbo says. “It’s quite possible that an insider holds onto the stock well beyond the next month and that the sale price might then be lower than the purchase price. Why then is it of any interest whether the share price goes up in the month after the purchase?”

He points out that regardless what abnormal returns Hvide believes he has proven, they reflect the company's excess returns resulting from insider trading – and not the insiders’ own excess returns, which requires using their actual holding periods.

“By using the actual periods, the insiders' excess return disappears in a statistical sense,” Eckbo says.

Sounds a bit strange

Ødegaard thinks it sounds a bit strange that there would be a large amount of insider trading by employees in major Norwegian limited companies, who do not perceive themselves as being legally bound to notify the stock exchange when they trade shares in their own company.

“The notification rules for insider trading are quite clear,” he says.

“It’s clear that people who trade shares in their own company have access to better information than other people. That means there’s also an opportunity for them to profit more than others on those kinds of trades.”

“Espen Eckbo and I took a closer look at this in the study we did. But we didn’t find that insiders as a group receive any higher returns than the average of other people who trade on the Oslo Stock Exchange. This doesn’t preclude some from doing so, but at an aggregate level we didn’t find any such excess return,” Ødegaard says.

Plenty of grey areas

Hvide points out that what is considered price-sensitive information in a company is not always clear.

“There are plenty of grey areas here,” he says, “both in terms of exactly what information might indicate that the price is going up, and to what extent this information is already incorporated into the share price of the company.

References:

Hans K. Hvide and Kasper Meisner Nielsen: Flying below the radar: Insider trading by executives below the top. Working paper, unpublished article. 2021.

B. Espen Eckbo and Bernt Arne Ødegaard: Board gender-balancing, network information and insider trading. Tuck School of Business Working Paper No. 3475061, 2021.

———

Translated by Ingrid Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no