What did nearsighted people do before the age of eyeglasses?

Glasses probably came to Norway about 400 years ago.

The Norwegian Institute of Public Health states that one third of Norway’s population is myopic – or nearsighted.

Quite a few people develop poor eyesight early in life.

The Nordic countries appear to have had glasses that have solved the problem for many individuals since the early 17th century. The first glasses were however invented in Italy around 1290.

But what did people do before that time if they developed poor eyesight already as 20-year-olds?

Status symbol

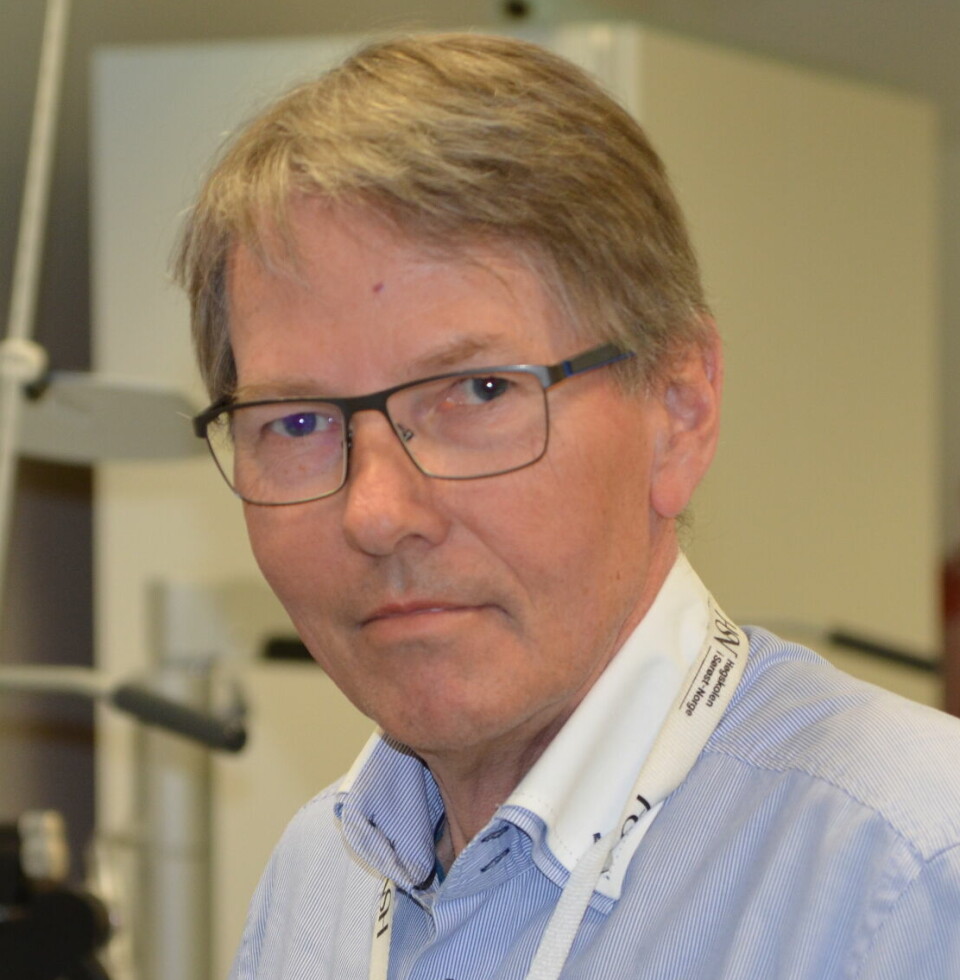

“King Christian IV of Denmark and Norway minted a coin with spectacles on the reverse in 1647, most likely indicating that glasses had become well known among the people by then,” says Magne Helland, “at least among the better-off members of the population.” Helland is an associate professor emeritus in optometry and wrote an article in connection with the 50th anniversary of the optometry programme at the University of Southeast Norway (USN).

Wearing glasses was probably an excellent way to show one’s status, writes Helland. A bit like glasses today that come in endless colours and shapes and have become an expression of one’s identity.

In 1974, more than 400 glass lenses were found in a shipwreck off the Bamble Coast in Vestfold og Telemark county. The ship probably sank around 1630 and came from London.

Limited knowledge about glasses' early beginnings

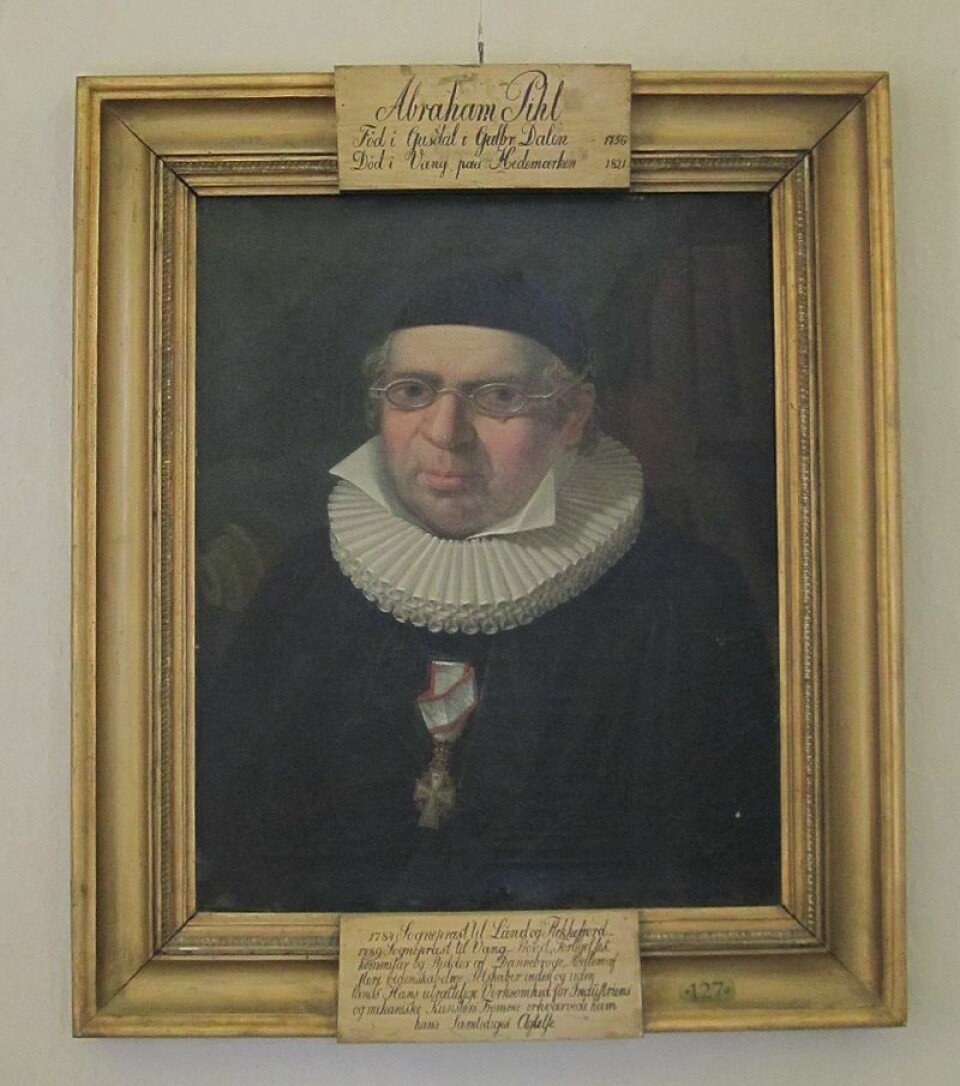

Old portrait paintings are a third important source that Helland has investigated in order to track down when the first glasses came to Norway.

Very few older paintings exist that depict people wearing glasses. The oldest example that he has been able to track down is from 1780, he writes in the article.

That portrait painting was of Abraham Pihl, a Norwegian architect, astronomer and watchmaker – who also worked with optics.

In other words, we don’t know very much about eyeglasses' first years in Norway. On the other hand, everything indicates that Norway did not lead the latest and greatest eyeglass fashions.

“We were probably a bit behind England and countries in Central Europe, and then the technology likely spread north with instrument makers and craftspeople who moved,” says Helland.

“Sweden has some documentation on the use of glasses that precedes documentation we have in Norway.”

Helland writes that initially a lot of people probably obtained glasses through travelling salesmen who sold them with standardized lenses.

Surely an early example of ready-made spectacle business, he quips.

Not much close-up work

Eyeglasses are not very old in the bigger scheme of things – at least not in the Nordic countries. What did people do before the age of glasses if they became myopic in their 20s, for example?

“If you go back several hundred years, close-up tasks weren’t as common,” says Helland.

No screens existed, obviously, and most people didn’t have to deal with a lot of small print and fine details either.

“Conditions are so different now, and yet our vision is still designed for relaxed viewing at a distance,” says Helland.

He explains that several muscles are involved in controlling eye movements and changing the focusing ability of the lens of the eye.

Didn't have the same need for glasses

“For close-up vision, the eyes have to turn inward and the lens of our eyes changes its strength. This requires muscle use,” says Helland.

“In this sense, our vision is not optimally designed for today's extensive use at close range.”

Up close, the same muscles are tensed, and in this sense, our vision is not made for our current needs.

Could modern-day close-up demands be the cause of myopia? Scientists disagree. Research by Helland's colleagues at USN does not indicate that. But one thing is certain: Close-up work can be tiring and can cause headaches without the help of glasses.

It’s no coincidence that taking a break from the screen to look out at the horizon feels so pleasant.

We spend up to many hours a day on small screens with small print – unless you prefer analogue and reading a book over digital. Either activity is a strain on the eyes.

“The situation wasn’t as critical a few hundred years ago. If you had astigmatism or were a little nearsighted, not wearing glasses wasn’t a real issue.”

What about the visually impaired?

If a person’s vision did not get in the way of everyday life, it might not have been considered poor eyesight. Today, on the other hand, glasses or contact lenses are recommended for even relatively minor vision defects.

It was thus possible to live perfectly well with myopia – or what we today consider to be nearsightedness. But how did individuals manage who were not only nearsighted to varying degrees, but visually impaired?

In the absence of historical sources, we have little concrete evidence for how the visually impaired fared, according to Helland.

“People who contracted an eye disease a few hundred years ago and could no longer see probably ended up on the sidelines and became less useful in society,” he says.

Simple plus power glasses

The first glasses – from the time they were introduced in Italy around 1290 until the 17th or 18th century – were plus power glasses, says Helland.

“They were intended for adults who gradually lost the ability to see well up close,” he says.

Our eyesight gradually declines from our early 40s, and our ability to see things clearly up close gets worse.

“The first eyeglasses that corrected for astigmatism appeared in the first half of the 19th century.”

In other words, the 400-year-old spectacles that were found off the Bamble Coast in Vestfold og Telemark county were quite a bit simpler than today's eyeglasses. You couldn't fine tune them to your vision.

The first instruments to detect vision defects were test lenses, test glasses and standardized charts to measure visual acuity.

Ophthalmologists had no good methods to determine visual defects or eye diseases before these aids and other instruments came along and knowledge improved – other than that a person had poor eyesight.

Died early and avoided cataracts

“Another interesting fact is that we live much longer now than in the past. Life expectancy 200 years ago was around 45 to 50 years,” says Helland.

In other words, Helland points out, many people died before they had time to develop a serious degree of the same problems that many people struggle with today, such as cataracts, glaucoma or impaired vision.

Today, with a life expectancy over 80, eye problems and diseases develop as a natural consequence of a long life.

Fortunately, we now have good remedies to treat these conditions. Cataracts can be removed with a relatively simple procedure, and glaucoma can be kept at bay for a long time with special eye drops.

A lot has happened in recent decades, especially since optometry programmes were established in 1972.

Change in behaviour may have led to increased myopia

Myopia has actually become more common in our modern world, says Rigmor Baraas, a professor at the National Centre for Optics, Vision and Eye Care (NOSØ) at USN.

“There is no documentation that our human eyes have undergone an evolutionary change. It’s more likely that our behaviour has changed,” she says.

“We’re seeing an increasing amount of documentation that indicates that myopia might be due to the big change from being outdoors a lot to being indoors a lot.”

Professionals talk about a myopia epidemic.

According to a 2015 news article in Nature, between 10 and 15 percent of the Chinese population was myopic around the year 1955. In 2015, the number was 90 percent.

“In East and South-East Asia, including China, the incidence of myopia in the early teenage years is often over 60 percent. When pupils leave upper secondary school, over 80 percent are nearsighted,” says Baraas.

Out for recess and keep your vision?

According to Baraas, the drastic increase of nearsightedness is linked to the restructuring of the school system in China following the Cultural Revolution. The increased educational pressure led to students spending more time at school.

There was more time in the classroom and much less time outside. Several studies show that outdoor time is important for delaying myopia.

“China is now in the process of restructuring the school system to free up more time for outdoor play and learning – to deal with the myopia epidemic,” says Baraas.

“Norway has a tradition for pupils in primary and secondary schools to go outside during recess. The incidence of myopia is low and shows no signs of increasing among children and young people here,” says the professor.

“The fact that the children have to go out during recess is probably very good for eye health, and also general health – and a practice that we need to ensure will continue in Norway.”

“It might also be that northern Europeans are genetically protected,” says Baraas.

She emphasizes that the research is still too limited to confirm anything about this connection and will continue to work on this with her research colleagues.

Not accessible to all

Ever better glasses have become available to people.

However, Baraas does not believe that glasses can be called common property just yet – even 400 years after a ship loaded with spectacles sank off the Bamble Coast.

“Only since last year has part of the cost of glasses been covered for Norwegian children through the social security system, regardless of strength. And families have to pay for the eye examination themselves. So I don't think we're quite there yet,” she says.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no