80 years since the famous experiment:

The starved men developed symptoms resembling eating disorders

Can hunger itself cause anorexia? The Minnesota Starvation Experiment sheds light on how a lack of food changes the body and mind.

Around this time of year, 80 years ago, 36 healthy young men reported to the University of Minnesota’s Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene in the USA. They were selected from over 400 applicants for a very special research project.

Namely, a semi-starvation experiment.

For six months, the participants would live on far fewer calories than their bodies actually needed.

“This study would probably never have been approved today,” says Professor Øyvind Rø at the University of Oslo.

Together with Lasse Bang from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Rø wrote an article about the Minnesota Starvation Experiment in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association in 2021 (link in Norwegian).

Wanted to help starving Europeans

By today's standards, the experiment is ethically quite questionable. But the justification was noble.

When the study began in early 1945, World War II was beginning to turn in favour of the Allies. The American researchers anticipated the imminent liberation of a starving European population.

They wanted to learn more about the physical and mental effects of malnutrition and to identify the most effective way to help these people gain weight again.

Starvation diet

The young men who volunteered wanted to make a contribution to humanity. Many of them held religious or ideological beliefs that had exempted them from military service. Now, they wanted to help in their own way.

After a three-month control period with a normal diet, the semi-starvation phase began.

The participants’ caloric intake was reduced to just under 1,600 calories a day. The meals were based on the diets available in war-torn countries and consisted of cabbage, potatoes, turnips, beans, and small amounts of pasta or wholemeal bread.

Active daily life

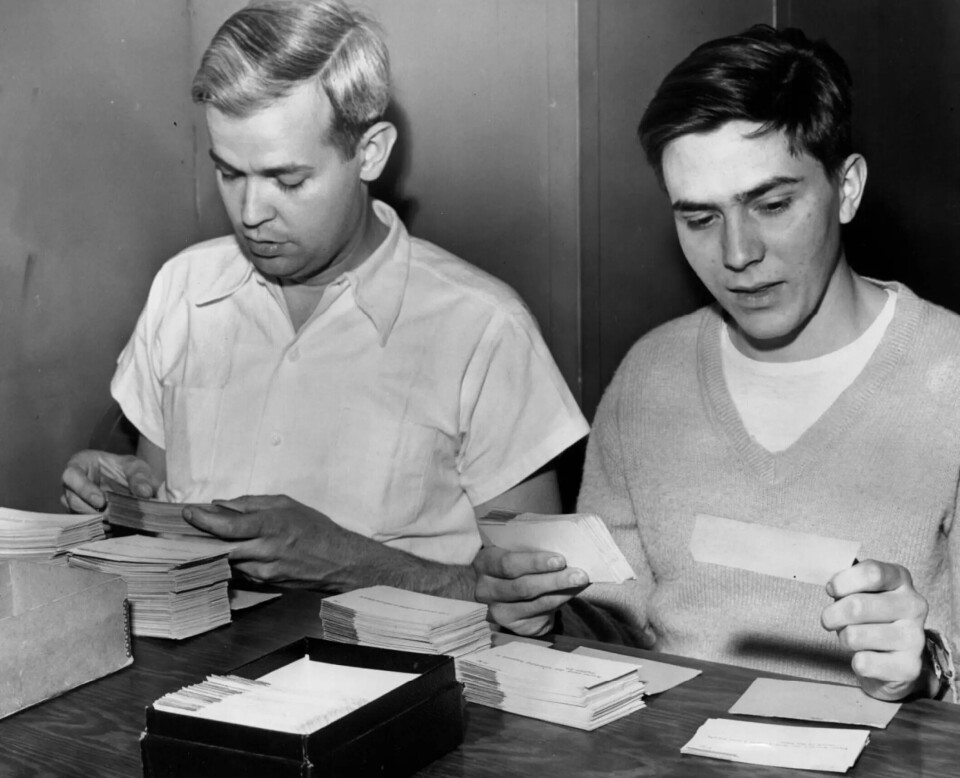

The men slept and ate at the laboratory but were allowed to continue working or studying and engaging in leisure activities. They were paired up to prevent anyone from being tempted to eat extra food.

Additionally, participants were required to walk on a treadmill for about five kilometres daily and perform various tasks for 15 hours per week.

The researchers ran a wide range of tests during the study, including measuring weight, blood pressure, pulse, stool, and urine. The participants answered questionnaires, performed cognitive tasks, and spoke with the researchers. They also kept diaries, which the researchers reviewed.

Cold and weak

In the months that followed, the participants rapidly lost weight. Their BMI dropped from an average of around 22 to a lean 16.4 – well below the threshold for underweight.

The participants experienced numerous physical symptoms. They had a lower pulse and felt cold and weak. Hunger also caused hair loss, dizziness, swollen joints, and constipation.

However, it was the psychological changes that were most noticeable, Rø and Bang wrote in 2021.

Changes in personality and body image

The men experienced major changes in their personality.

“They became more irritable, short-tempered, and rigid, and exhibited more symptoms of anxiety. The men withdrew socially and lost interest in sex,” says Rø.

Some participants developed such severe mental health problems that they were hospitalised.

Many also became obsessed with food, psychiatrist Sonia Sarró writes in the journal Neurosciences and History.

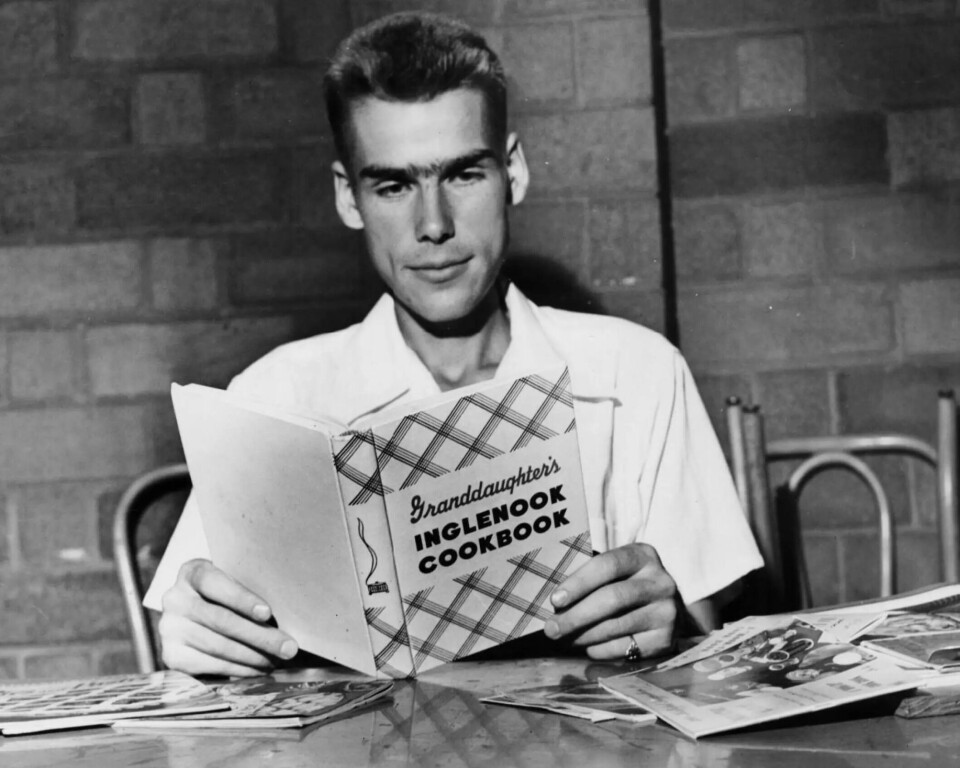

The men talked about food and found recipes. They developed rituals around meals, such as crumbling their food, chewing very slowly, or using excessive amounts of salt and spices. Some became addicted to chewing gum.

Several participants also developed a distorted body image.

Some thought that people of normal weight appeared overweight. Others did not see themselves as particularly underweight but acknowledged that the other participants were.

When the experiment was over and the men were given enough food again, some expressed concern about gaining fat in certain areas of their bodies.

Symptoms resembled eating disorders

Although the results from the Minnesota Starvation Experiment are 80 years old, they remain highly relevant, particularly for understanding eating disorders, says Rø.

He has studied these conditions for many years and has helped create the current guidelines for treating eating disorders in Norway.

"Many of the symptoms that arose purely from starvation in the Minnesota experiment are strikingly similar to those seen in anorexia," he says.

This includes a distorted relationship with food and body weight, increased depressive symptoms, anxiety, and personality changes, such as more rigid thinking and an obsessive focus on details.

Hunger can cause eating disorders

The old results raise some important questions:

Are many of the psychological traits seen in anorexia simply symptoms of a starved brain?

Could it be that these traits were not necessarily present beforehand and did not cause the eatind disorder, but that starvation itself can help trigger and sustain the illness and its associated psychological changes?

This could mean that random dieting or hard training periods could become a trap, suggests Rø.

A vicious cycle

“You might think that someone who is vulnerable to eating disorders and who enters a period of starvation could become caught in a vicious cycle,” says Rø.

“Weight loss causes psychological changes, making you more perfectionistic, anxious, and concerned about your weight and body image. This, in turn, leads to further weight loss and intensifies the psychological problems,” Rø says.

Rø emphasises that this does not happen to everyone who loses weight. However, some people have genetic, psychological, or social vulnerabilities that predispose them to eating disorders. He illustrates this with a hypothetical example:

“Imagine 100 random high school students are tasked with losing two kilos in a month. Afterwards, almost all of them would easily return to their normal eating habits.”

“But for a small percentage, this dieting could trigger the dynamics of an eating disorder,” he says.

Perhaps the starvation period leads to epigenetic changes – where certain genes are switched on or off – thereby increasing the risk of developing an eating disorder.

Important weight gain

"This is the main argument for why a crucial part of treating anorexia is alleviating the starvation state," says Rø.

“As patients regain weight, some of the psychological symptoms gradually diminish, allowing them to recover from the eating disorder,” he says.

However, the professor also notes that this does not happen for everyone. Many continue to struggle even after their weight has returned to normal.

This is likely caused by a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors.

In recent years, research has suggested, for example, that disturbances in intestinal flora might contribute to maintaining the abnormal state in the body. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences are working to uncover more about this.

Longer recovery and more calories than expected

80 years ago, in Minnesota, the participants in the study overcame their psychological symptoms once they received adequate food again.

However, their weight gain required more calories than expected. Many participants were still underweight at the end of the three-month refeeding period.

There was also significant variation among the participants, similar to what is seen in anorexia patients.

Some of the men returned to normal eating patterns and weight quite quickly, although many initially felt they had lost control over their eating. Some initially gained a lot of weight before their eating habits and body fat normalised.

For others, it took several years to regain a normal relationship with food. Ten participants later reported that they were permanently changed by the experience, according to Sarró.

Important many decades later

The participants in the Minnesota Starvation Experiment wanted to contribute to the war effort. Even many decades later, almost all of them stated that they would have done it again, despite the difficulties they endured during the study.

Many were disappointed that the results were published long after the war ended, reducing their impact on the people of Europe.

Nevertheless, their efforts continue to have significance, albeit in a different scientific field.

“The study emphasises that individuals who are underweight must receive adequate nutrition for their physical and psychological symptoms to normalise,” says Rø.

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.