A new overview provides an even more accurate picture of polar sea ice in the past 30 years

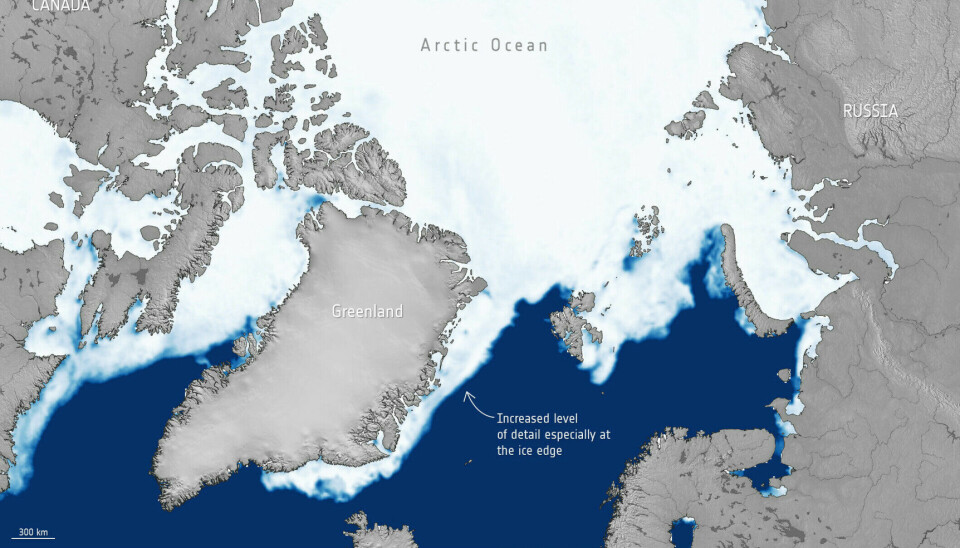

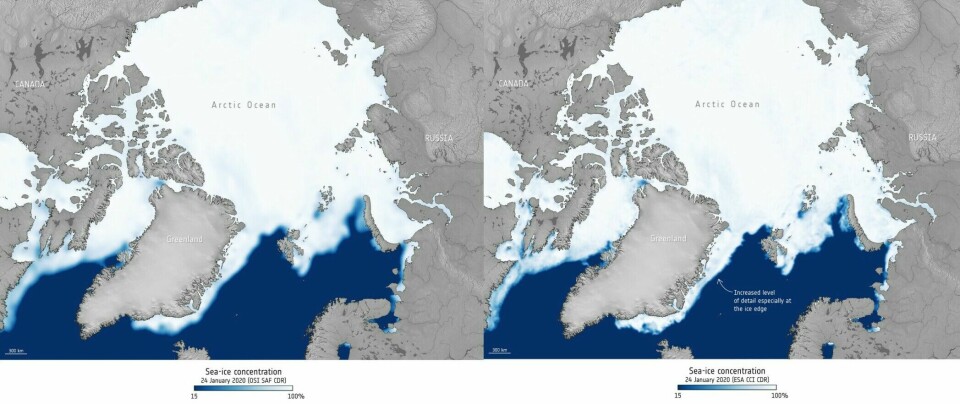

The new information makes it possible to see what has happened to sea ice locally along the coasts of Antarctica and Greenland.

The European Space Agency (ESA) has released a new dataset for Arctic and Antarctic sea ice.

The data set is based on satellite observations and spans 30 years, from 1991 to 2020. That’s ten years shorter than the full satellite archive. In return, the new overview offers more details, the ESA reported on its webpage.

The overview will help climate scientists gain an even better understanding of the effects of climate change in the polar regions.

Thomas Lavergne is a researcher at the Norwegian Meteorological Institute and has headed the project through ESA's Climate Change Initiative.

Now we’ve done the job

“Climate scientists use existing data. They then come back to us and tell us what they are missing, such as details from along the coast of Greenland. Now we’ve done the job, we’re delivering new data with higher resolution and more details,” Lavergne says.

Researchers will need to work with the new data set to see what it can tell us. Lavergne nevertheless has some thoughts about the kinds of information the data set will contain.

Sea ice and ice on land

There are several types of ice on Earth: Alpine glaciers in the mountains, thick inland ice in Greenland and Antarctica, as well as polar sea ice. Sea ice is frozen seawater that floats on the surface of the ocean.

When ice sheets melt, sea levels rise. Melting sea ice does not affect sea level, at least not directly.

“But the large areas with inland ice are protected in a way by sea ice,” Lavergne says. “You have a good deal of sea ice around Greenland, and you have sea ice all the way around Antarctica.”

Wave protection

Lavergne gives two examples of the kinds of insights the data set can provide.

Antarctic sea ice dampens large waves in the ocean around the continent, Lavergne said.

“If there is no sea ice, then these big waves can reach the coast and destroy the land ice,” he said.

If waves are allowed to hit the ice on land in Antarctica, it can accelerate melting,” Lavergne said.

“It’s more and more important to have good information about the sea ice around Antarctica. For example, it’s good to know if the sea ice cover extends all the way to the land ice.”

Like a lid

Waves are not the biggest problem in Greenland, however.

“The sea ice there is like a lid on a kettle containing boiling hot water. If you remove the sea ice, the heat from the sea can escape. This can produce a lot of steam, which may lead to snow or rain in Greenland,” he said.

Better information about the sea ice around Greenland can consequently provide more insight into precipitation in the area.

Confirms what we already know

Scientists already have a good overview of the large-scale changes that are underway in the Arctic and Antarctic.

“The new data do not provide much additional information about large areas like the entire Arctic or Antarctic. These data are more about providing better local and regional information,” Lavergne said.

The data confirm what was already known. The sea ice in the Arctic has been decreasing consistently, every month of the year, Lavergne said.

The average thickness of the ice has decreased from approximately three metres before 1980 to approximately two metres now, according to the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research at the University of Bergen.

The extent of summer ice in September has decreased by approximately 40 per cent since 1979.

Record low sea ice in Antarctica

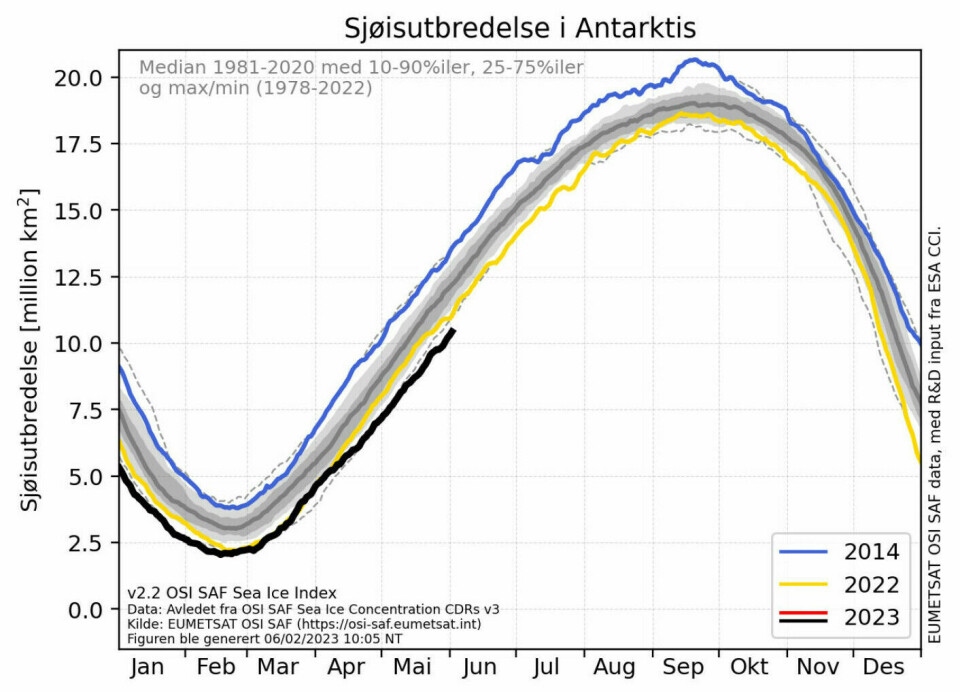

The sea ice in Antarctica has not decreased in the same way.

Southern sea ice almost disappears in summer. This is normal, according to an older article from forskning.no (in Norwegian).

“Antarctica has had a period of fairly steady development. Ice amounts did not go up or down consistently. But in the last six or seven years, we have seen much less sea ice around Antarctica,” Lavergne said.

“Right now we have a record low extent of sea ice around Antarctica as measured from satellite data,” he said.

Lavergne says that it is unclear whether the reduced sea ice extent is a short-term abnormal situation or whether it is the start of a longer-term trend.

“The globe is getting warmer. In the long term, we are fairly certain that there will be less sea ice around Antarctica as well, but we do not know how quickly this will happen,” he said.

Must work with the raw material

The new data set is based on pictures taken from satellites that orbit the Earth.

“It’s not easy for climate scientists to use these images directly. My job is to derive sea ice information from the satellite images,” Lavergne said.

The same type of satellite has been used from 1991 to 2020.

The satellites used for this purpose are called passive microwave satellites, because they measure microwave radiation emitted by the Earth.

Microwave radiation is radiation that has a longer wavelength than both infrared radiation and the light we can see.

“We don't see microwaves, but everything around us emits very small amounts of microwave signals,” he said.

“Warmer things typically emit more microwaves than colder things. Sea ice, for example, emits different amounts of microwaves than the surrounding ocean. This is how we distinguish between sea ice and open sea in the satellite images from these satellites,” he said.

There are also active microwave satellites that send out microwaves and record what comes back, Lavergne said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no