Fat shaming makes people gain more weight

People are not motivated to lose weight if they are told they are fat. They just get fatter.

In the Norwegian tv-series "A fat life", tv-personality Ronny Brede Aase examined what researchers now know about overweight and obesity.

One researcher presented knowledge that made an extra strong impression on him, as he explained at a Research Communications gathering in Oslo in late December.

“When I met Trine Tetlie Eik-Nes in the last episode, she shared an incredibly painful truth with me,” he told the audience.

The least popular friend

Ronny Brede Aase himself is happy in his admittedly big body. He tells his viewers in the series that his life is full of joy, burgers and beer.

But Eik-Nes, an associate professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), told Aase about research that shows that not everyone is as comfortable with their situation as he is. Many people experience widespread discrimination because of their body size.

For example, there is research that shows that an overweight child is the least popular child when it comes to making friends.

Parents give overweight children less financial support than normal-weight children, according to other research.

Teachers have negative attitudes towards overweight children, another study shows.

Overweight people are paid lower salaries and are less likely to be promoted, other researchers have found.

There is widespread discrimination, even in the health care system. Numerous studies show that overweight people are taken less seriously and are allotted less time for treatment.

Less tolerance for overweight people

Eik-Nes also told Aase about a relatively new, large study from the USA which shows that people have become much more tolerant of people of different genders, orientation or race — except when it comes to one group.

People have become less tolerant of overweight people, not more.

We are moving towards being more liberal and generous to those who look different, have different traditions and other ways of living life than ourselves. This is a strength. But when it comes to obesity, none of this means anything! Things have actually gone the other way.

Aase said in an interview with sciencenorway.no that he was surprised by what he heard.

“I had thought we had come further. I feel that we have gained an increased respect for each other in society. We are moving towards being more liberal and generous to those who look different, have different traditions and other ways of living life than ourselves. This is a strength. But when it comes to obesity, none of this means anything! Things have actually gone the other way,” he said.

During preparations for the series, Aase and his colleagues found a clear pattern.

“It seems to be a common perception among people that the best way to treat obese people is to tell them: ‘You’re too fat now. You have to sharpen up and pull yourself together’,” he said.

“But Trine Eik-Nes’s research shows the opposite. When you give people a bad conscience, you only hurt them more,” he said.

Health professionals not well informed

It isn't only ‘most people’ who think like this, Eik-Nes told sciencenorway.no.

Even health care professionals who treat overweight and obese individuals still believe it’s important to let people know how big they really are. And that measuring and weighing themselves can motivate them to change their lifestyle.

“Health professionals often have no idea about the experience of having a body that is stigmatized. Most people who work in the field are of normal weight and perhaps less understanding of those who struggle and are insecure in their body,” she said.

Many people are probably more curious than previously about new solutions for patients that they are unable to help. But dieting and exercise are still the preferred approach for changing lifestyles, Eik-Nes said.

Taking fat shaming seriously

In recent years, several new studies document that diets and exercise do not work that way, according to Eik-Nes.

On the contrary.

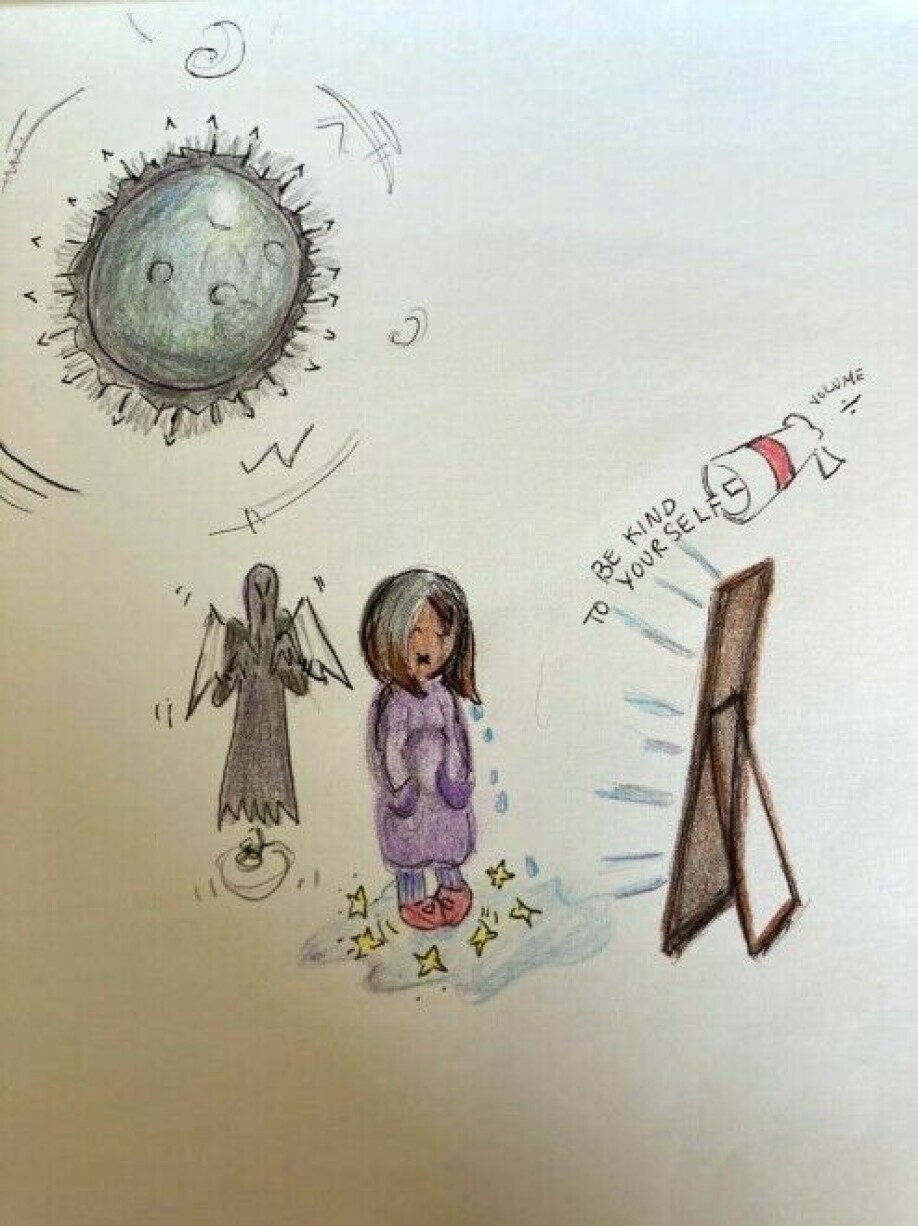

When we tell people that they are fat and should eat less and exercise more, this information doesn’t lead to positive changes. People who are stigmatized because of their weight are much less able to exercise or eat properly. They just get fatter and sicker, research shows.

Research finds that overeating is a way to master what is called internalized stigma. This means you have incorporated strong negative attitudes towards yourself and think that you are a worthless human being.

“If we use this new knowledge, I think we can help many more people,” Eik-Nes said.

She herself has undertaken research on what she calls ‘the stigma of being overweight’, which in English is often called ‘fat shaming’ .

Eik-Nes has travelled to different places in the world to look for treatment methods that have incorporated the new research.

She found none.

So she decided to create a new treatment plan herself. She and specialized physiotherapist Kjersti Hognes-Berg have done this in close contact with user organizations.

Obesity and eating disorders

In an ongoing research and treatment project, researchers and therapists at NTNU are using as their starting point people who seek treatment for obesity and who also have an eating disorder. This is a group of patients for whom there is currently no good treatment.

The project is a collaboration between the obesity outpatient clinic at St. Olavs Hospital and an overeating team in mental health care at DPS Stjørdal, a district psychiatric centre, that has been established in connection with the project.

If an eating disorder is discovered in addition to morbid obesity, the patient is offered 30 hours of treatment by Eik-Nes and her colleagues.

Learning about guilt and shame

Unlike other obesity treatments, none of the patients in this project are told to lose weight.

They are also not told to start exercising.

Patients simply learn about guilt and shame.

“We try to treat eating disorders and weight gain by actually providing knowledge about how things are related to the patient. Why do some people become overweight? What do bullying and discrimination and attitudes in society do to us?” Eik-Nes said.

This is a completely different view of the prevailing knowledge today, she said.

We know from research that obesity is very complex.

As early as 2013, obesity was recognized as a disease by the American Medical Association.

Researchers believe that there are many possible factors behind weight gain. Some of these factors include genes, hormones, medications, mental illness and a number of other things inside and outside of your body.

Almost no dropouts

To date, almost 80 patients have gone through the treatment plan by Eik-Nes and her colleagues at St. Olavs.

Eik-Nes is surprised at how well the treatment has been received.

Many of the usual treatments for obesity and eating disorders have dropout rates that are over 50 per cent, she says.

“In 2.5 years, we have only had one person who has dropped out. That’s quite startling, because this is actually pretty tough treatment,” she said.

Most health care providers who have created obesity treatments don’t take into account mental health and how that affects the body. The challenge is that there are two worlds that don’t usually talk to each other, Eik-Nes said.

The researchers have published a pilot study with 42 patients who received treatment for ten weeks. Here they believe they have reached their first goal, which was to see if it was even possible to conduct this kind of treatment.

The patients also reduced their overeating after the course, she says. They have been less anxious and become somewhat more socially active.

Courses for parents

The patients recognize themselves in the research they are presented with, according to Eik-Nes.

Parents may pinch them in the belly or serve them different food to eat than their siblings, Eik-Nes says. “I think that parents and family often mean well. They don’t allow their children to get fat. However, it’s extremely unsettling for a child to hear negative comments about their body from parents, siblings and relatives.

“Many say that they themselves have incorporated society's attitudes into their own consciousness, that they are fat, incompetent, lazy and stupid,” she said.

This perception is so strong that they also think this way about other overweight people.

These attitudes are established early in life.

Many overweight and obese people tell stories from their own childhood, where their family has stigmatized them because they eat too much. Parents may pinch them in the belly or serve them different food to eat than their siblings, Eik-Nes says.

“I think that parents and family often mean well. They don’t allow their children to get fat. However, it’s extremely unsettling for a child to hear negative comments about their body from parents, siblings and relatives,” she said.

That makes it important to reach parents early and before they transfer negative attitudes to their children, she said.

Eik-Nes and her colleagues have now started their own parenting course called ‘Secure bodies — secure children’. The course gives parents information about how unhelpful it is to comment that their kids eat too much or that they aren’t active enough.

The course has been tested in Australia and the USA with good results. They have just completed their first pilot project in a Norwegian municipality and will publish their results in an academic article.

Don’t talk about dieting

The course teaches parents strategies for how to deal with unhealthy eating behaviours and negative relationships with the body.

“The first instinct is often to start putting the child on a diet if he or she becomes overweight. This has very negative consequences. It makes the child feel like something is very wrong with their body and that has to be changed,” Eik-Nes said.

“We warn parents not to put their children on diets. They should also not talk about dieting in the family or comment on their own or others' bodies. Children should feel safe and live in a shame-free home,” she said. “It’s possible to set boundaries, without stigmatizing a person.”

“Children can learn that they should move their bodies and use them, and not think about how they look. And that there is no such thing as yes- and no-food, but ‘occasional food’ and ‘everyday food’,” she said.

Must see the whole person

Kai Brynjar Hagen, who recently resigned as municipal chief physician in Bodø, welcomes the new research. Until recently, he was also chief physician at the Regional Centre for Morbid Obesity, under the Northern Norway Regional Health Authority, Helse Nord.

When he started treating obesity, he came with deep experience in general medicine.

“I was used to seeing the whole person. As a result, I was quite surprised when I experienced how the health service treated patients who were overweight or obese,” he said.

When you finally dare to go to your GP and ask for help with your obesity, you may already at this point encounter people who have no comprehension of the problem, Hagen said.

“You’re measured, weighed and catalogued. Then you are sent to a local hospital, where the help you can get is quite variable,” he said.

The hospital may refer you to a regional centre for morbid obesity, where you may be offered an assessment and follow-up and can be referred to a rehabilitation centre.

Some are also referred to psychiatric trauma treatment, if necessary.

Some receive drug treatment, Hagen said.

Patient history important

When he started working with obese patients, Hagen discovered that the examination by a specialist often took place during a short consultation.

He quickly came to oppose this way of treating patients.

“I wanted to set aside time for a proper dialogue and demanded to spend two hours on each patient, which is very unusual in the daily operations of a hospital,” he said.

Hagen believes that it is important to gain insight into the patient's life history.

“As a doctor, I have general knowledge and experience. But this needs to be reconciled with the patient's knowledge of their own history so we can gain new, deeper insights. The patient's knowledge is just as valuable as medical knowledge,” he said.

Common characteristic

Some choose to hurt themselves. Some choose drugs. Others exercise a great deal or become shopaholics.

Hagen has talked to roughly 800 patients about their obesity, and has found a common characteristic in several of them.

He and his colleagues wrote a research article about this in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association last year.

“I became aware that there is a connection between stressful events in your life and the development of obesity,” he said.

He has also written about this in the book ‘Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient’.

Hagen says it’s a ‘beautiful moment’ when a patient discovers that there is nothing wrong with their own personality, but that the reason why things started to go wrong is that something happened to them in their life.

It’s important to understand that appetite and satiety are controlled by a finely tuned mechanism. Many physiological processes can be disrupted by traumatic stress, he says.

“When we are exposed to trauma or other stress that exceeds our coping ability, we can experience emotional pain or a harmful feeling of stress. One consequence is that a lot of your energy goes into dealing with these feelings. Then we do what it takes to get a break, to not feel,” he said.

“Some choose to hurt themselves. Some choose drugs. Others exercise a great deal or become shopaholics,” he said.

But many choose to regulate their emotions with food.

Stigma is a big — but known — problem

Jøran Hjelmesæth is head of the Centre for Morbid Obesity at Vestfold Hospital and a professor at the University of Oslo.

He completely agrees with Eik-Nes and Hagen that stigma is a big problem when it comes to obesity. If the person begins to hate him or herself, it can also aggravate the situation.

Hjelmesæth therefore thinks that it is both interesting and important that someone looks at the treatment of this patient group with new perspectives.

But being aware of stigma is nothing new in the treatment of obesity, he said.

“We have been talking about this for many years. We take this into account in our daily treatment,” he said.

In contrast to Eik-Nes and Hagen, however, Hjelmesæth doesn’t think that it necessarily helps people who have a weight problem if they are told why they have become obese. He also doesn’t know of any evidence that people lose weight by understanding why they have developed obesity.

“There’s very little we can do about what has happened earlier in life,” he said.

Two ways to handle weight

Hjelmesæth says there is a lot of documentation about the principles they use in their treatment at the Vestfold Hospital Centre for Morbid Obesity.

“Our treatment is to give concrete, individual or group-based advice on how to lose weight. It is only possible to do in two ways. The way that is best for most of our patients is to eat fewer calories,” he said.

However, if it is clear that an eating disorder is more troublesome than the weight, they recommend that the eating disorder be treated first. Then psychologists or psychiatrists take over, he says.

We have documented an average of ten per cent weight reduction in our patient group after lifestyle treatment. This is good for the health of many of our patients, but less than many patients want.

“We can’t treat obesity and overeating at the same time. If the patient's main problem is a severe overeating disorder, they need to be treated for this, and then we’re not talking about weight. However, if the patient wants help with weight reduction, the treatment will be directed using common principles for weight reduction,” he said.

Good results from surgery

In addition to teaching patients to eat fewer calories, obesity surgery is another option.

“This is where we have the best results,” Hjelmesæth says.

“After weight-reduction surgery, patients lose an average of 25 to 30 per cent of their body weight over one to two years. Thereafter, they see a gradual average increase of 0.5 to 1 per cent annually,” he said.

When it comes to traditional treatment without medication, the duration is unfortunately shorter, he says.

“We have documented an average of ten per cent weight reduction in our patient group after lifestyle treatment. This is good for the health of many of our patients, but less than many patients want. A number of international studies show that if you add a weight-reducing drug, you can add an average of 5 per cent weight reduction over one year,” he said.

Surgery resulted in less overeating

Hjelmesæth says that researchers at the centre in Tønsberg in collaboration with colleagues in Tromsø have tested the effect of cognitive behavioural therapy in people with morbid obesity before they undergo weight-reducing surgery.

The study consisted of one group that received behavioural therapy for ten weeks prior to the operation. Another group with similar patients received regular follow-up with a focus on lifestyle change.

It turned out that therapy had a great impact on both disordered eating patterns and other mental disorders such as anxiety and depression, which also more often affect people with obesity. The patients in this group also had less uncontrolled eating, less impulse eating and a greater ability to limit themselves.

However, when they examined the same patients one year after they had undergone bariatric surgery, it turned out that the surgery also led to less emotional eating.

“That meant the effect of the behavioural therapy disappeared,” Hjelmesæth said.

- RELATED: Is ultra-processed food making us fat and sick?

- RELATED: Eating less processed foods gave weight loss and lower risk of heart disease – also among men on a high fat diet

Planning for 30 per cent dropout

Hjelmesæth says that when they plan clinically controlled studies, they take into account that there can be up to a 30 per cent dropout rate. The researchers consequently include more patients in their study so they can find real differences between different treatment methods, even factoring in such a high dropout rate.

“These are studies that run over a period of one year, which in my opinion is the minimum time to be able to assess the clinical significance of a study. Ten weeks is too little to know if the results will persist in the long run,” he said.

Viewers responded

When the last episode of the NRK series ‘A fat life’ had streamed across TV screens this spring, Ronny Brede Aase's inbox was filled with feedback from viewers.

Many told him that they have always felt looked down on because they are a few kilos overweight.

“They have been told that they are lazy, irresponsible and have little impulse control,” he said.

He also received a lot of feedback from people on the other side of the scale, people who are underweight.

“It seems that the series appealed to a lot of people who have experienced other people talking badly about their bodies their whole lives, no matter whether they are too big or too small,” he said.

People want fake news about this

Aase believes that we as a society must accept the new research. We can’t pretend it doesn’t exist.

“When it comes to the body, exercise and diet, it seems like people just want ‘fake news’. By that I mean that people think it's okay to continue to believe that it's easy to lose weight, while the boring truth is that research shows it certainly is not,” he said.

Every single day we are fed information through the media that it is very easy to lose weight. It’s a story the media sells and it’s a story most people will buy, Aase said.

“This in turn means that more people are fat shaming people who are obese. Because most people don’t manage to lose weight. The boring truth is that it's not that simple,” he said.

His most important message after learning a lot about obesity research is:

“Take care of your body in a way that allows you to live well and enjoy yourself and thrive in the life you have. This means that you should make dietary changes that you can live with for the rest of your life. And by all means stop badmouthing other people's bodies!” he said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no