Is it really possible to find water with dowsing rods?

For physicist Arnt Inge Vistnes, dowsing is in the blood. He is one of the few researchers who has studied the phenomenon.

Perhaps you've seen someone dowsing or tried it yourself. Some people use a Y-shaped twig or rod to find buried pipelines, leaks or places in the ground with a lot of water.

Above the place where water is suspected to be, the rod pulls towards the ground, as if being drawn by a mysterious force. What is actually happening here?

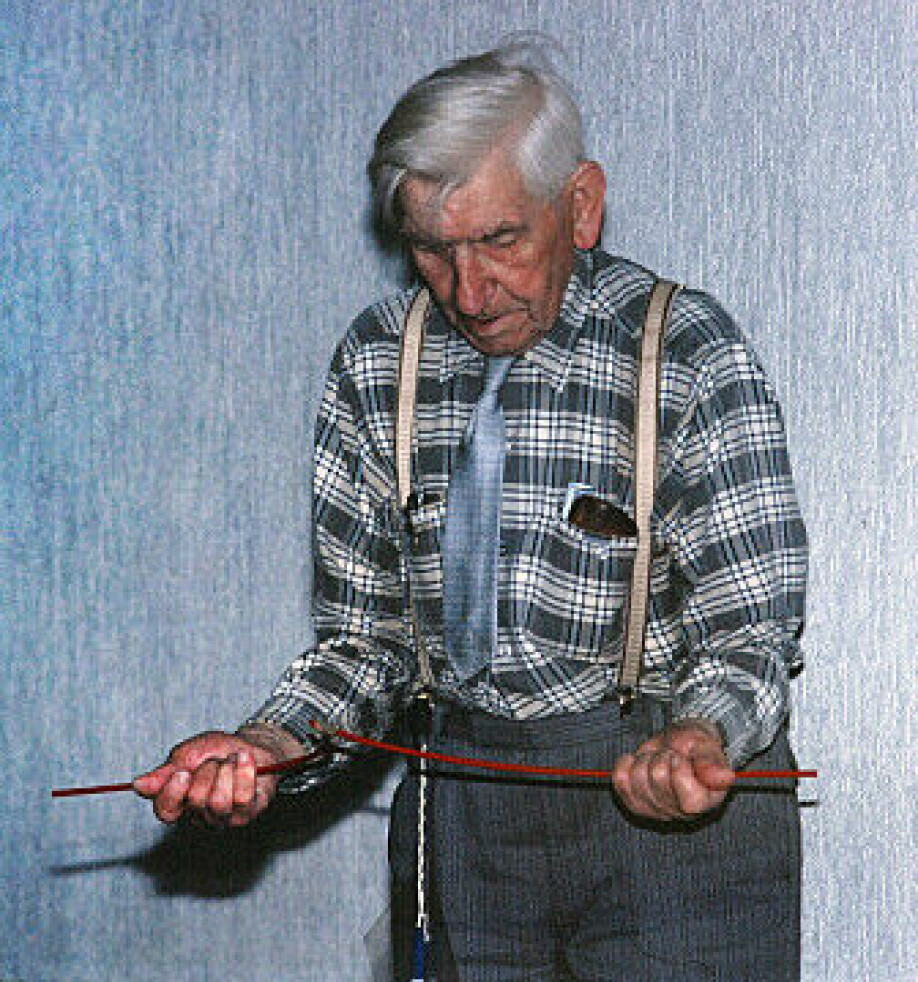

Svein Tømmerdal from Leksvik in Trøndelag county is one of the people who find water with dowsing rods. He prefers to use birch, because it is tougher.

He explains that he holds the twig ends in front of him with a firm grip, with his thumbs out to the side.

“If I come across water, the twig goes up for me. For some dowsers, it goes down.”

“You have to have a fairly firm grip. The twig twists the bark, at least in the spring,” Tømmerdal says.

Tømmerdal can find veins with water or good places to build a well using the dowsing rod.

He also says he is able to precisely measure the depth of the veins with the help of the rod. He takes a few steps to the side, and when the twig dips again, he can calculate the depth by imagining a right-angled triangle.

Tømmerdal believes that there must be an explanation for what makes the rod move. Not everyone who tries dowsing gets a reaction.

“We must have something in us that receives the radiation or the energy,” he says, wondering.

Could there be something to dowsing?

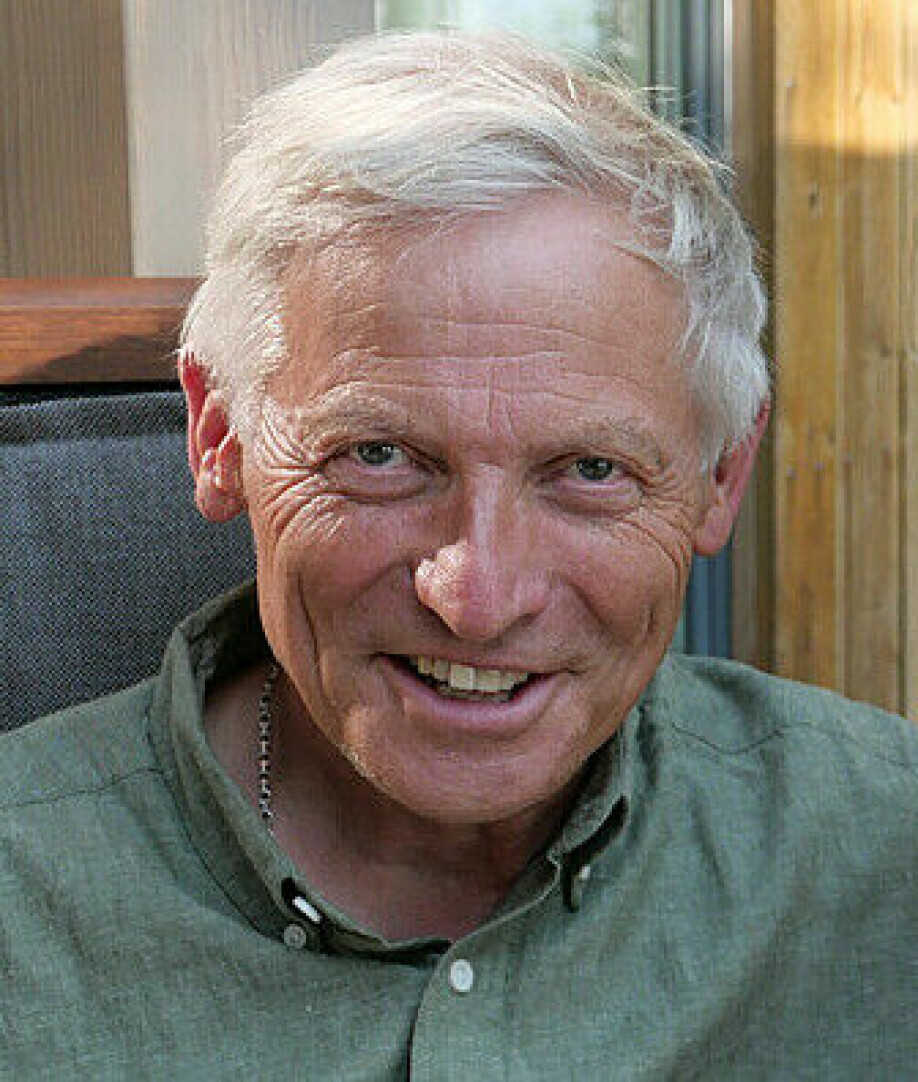

Arnt Inge Vistnes has also wondered what it is that makes someone get dowsing results. He is one of only a few people in Norway to have researched dowsing.

Is there anything special in the places where it happens? Or, he wondered, could it have something to do with magnetic or electric fields that affect the body?

Perhaps some people are sensitive enough to notice these forces?

Vistnes had the requisite background to find some answers. He is a physicist and now professor emeritus at the University of Oslo.

Dowsing was not an unknown concept for him.

“My grandfather did it in a big way and my great-grandfather did too. You could say it’s in the family,” Vistnes says.

Earth ray radiation

Vistnes' great-grandfather was a naturopath. So was his grandfather, who was called "Second Sage." He used a dowsing rod to detect the earth’s radiation. He would neutralize the earth rays in an area to alleviate health ailments.

Earth radiation is a non-scientific term that has been used to explain what causes a dowsing rod to locate water. It has been suggested that earth radiation occurs where there are water veins.

Others have suggested that earth ray radiation is like an underground net, independent of water, and that it has an impact on health.

“My grandfather had so-called supernatural abilities and in a way was the ‘man with warm hands’ of the time. He had a lot of success with dowsing,” says Vistnes.

Caught his grandfather red-handed

Vistnes himself had mixed feelings about the practice.

“I caught my grandfather red-handed once as a child when he was going to neutralize earth rays.”

He was going to demonstrate a new and effective remedy at my father's home. He said that there were two ways it could be set up: one worked, the other did not.

First he set it up so that it didn’t work.

“When he walked through the house he found earth radiation the whole way,” says Vistnes.

“Then my grandfather set it up so that it should work. When he walked around he found no earth radiation in the house.”

“What he didn’t know was that I had switched things around so that it wouldn’t work.”

Initiated experiment

Vistnes reflected on the episode afterwards.

“At the same time, this whole matter sat so deep in me, that even though I was a little sceptical, I believed that there might still be something there,” he says.

Vistnes recently wrote about his experiences in the latest issue of the journal Fra fysikkens verden (From the World of Physics), which is published by the Norwegian Physical Society.

In the 1980s, he set up a large-scale experiment.

Vistnes first wanted to find out whether dowsers would actually find earth radiation in the same places. Afterwards, his plan as a physicist was to investigate whether there was anything special about the places the majority of dowsers had pointed out.

Could it be that they were discovering places with weak electric and magnetic fields, for instance?

No one agreed

Twenty-five well-known dowsers joined the experiment. They conducted a survey in one corridor. The zones where the dowsers had a reaction were noted. The experiment was double-blind, and the subjects were not told where the others had found something.

It turned out that the dowsers found earth rays in completely different locations.

“When you have 25 dowsers that go out and none of their findings overlap, I just had to shelve the project,” says Vistnes.

Investigating whether anything was physically different about the places that had been marked was pointless, since the experiment didn’t show any agreement on where these places were.

The experiment wasn’t published. But Vistnes has now written an article about it in the journal Fra fysikkens verden.

Anders Bærheim, Steinar Hunskår and Bjørn Bjorvatn reported about a similar experiment in the journal Tidsskrift for den norske legeforening. Four experienced dowsers searched for patterns of earth rays in a gymnasium. No agreement resulted between their findings.

Vistnes also did a lot of research from 1987 to 2005 on whether electric fields could affect people’s health and work environments. He was interested in electromagnetic hypersensitivity and initially wondered if it might be related to dowsers’ experiences.

“I’ve actually come to the conclusion that there isn’t much to either electrical hypersensitivity or dowsing,” he says.

Dig deep enough and you can usually find water

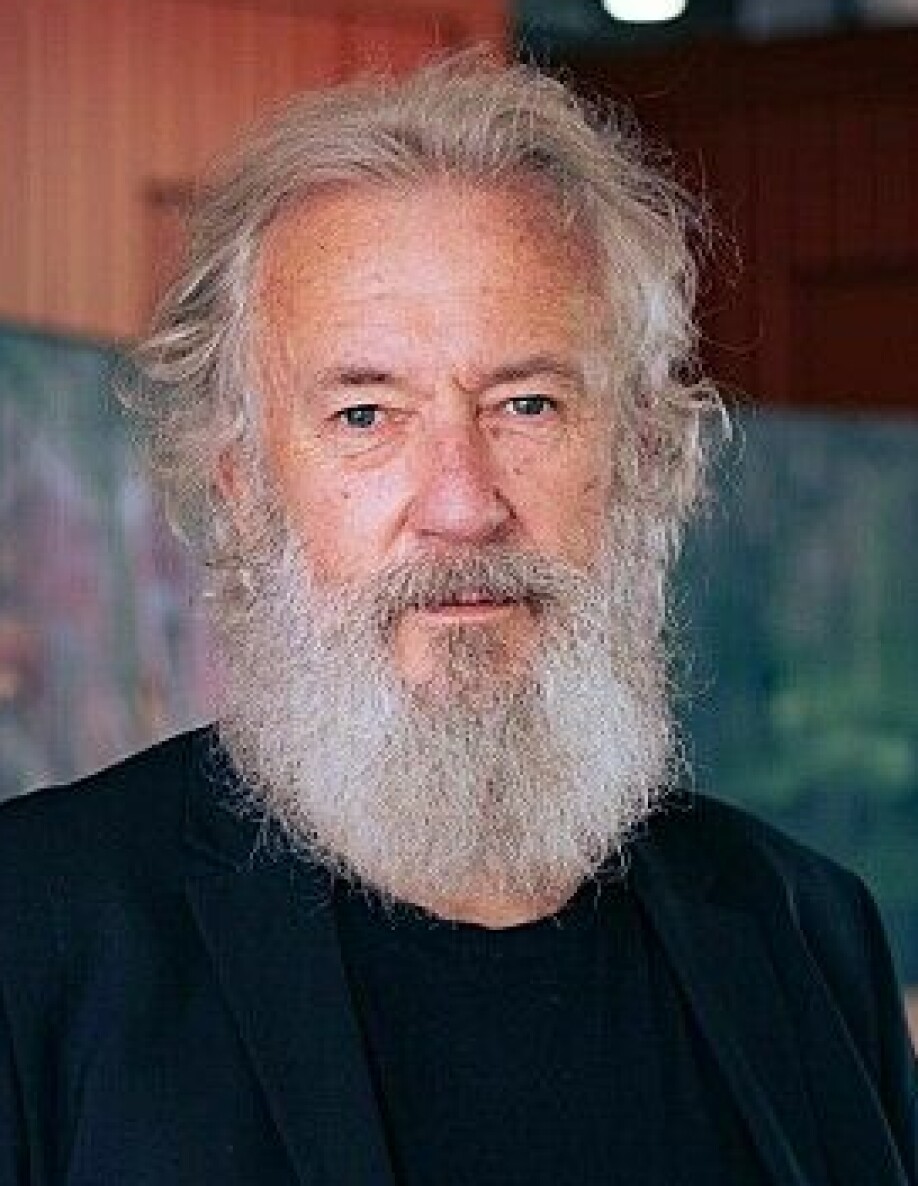

Erik Tunstad is a biologist, author and non-fiction writer. He was the editor of forskning.no (the Norwegian version of sciencenorway.no) from 2002 to 2009. He is familiar with dowsing, but from a sceptical perspective. He co-founded the organization Skepsis in 1989.

Over the years, Skepsis has attacked pseudoscience and claims of supernatural phenomena.

“I’ve been interested in the topic, so I’ve spent time with people who have been looking for water. They often find it,” says Tunstad.

“I’ve often been impressed and thought how strange it was. The dowsers were incredibly precise. But then you can say, ok, what if he’d dug over there instead, would he still have found water?”

“The problem is that you can dig just about anywhere you want in Norway, and if you go deep enough, you’ll find water,” he says.

Water veins?

“Dowsing is based on a notion that water runs in veins,” says Tunstad.

But most of the time it doesn’t.

Groundwater is the part of the subsoil where cracks and pore spaces are all completely filled with water, according to Store Norske leksikon, the Norwegian online encyclopaedia.

Groundwater is everywhere, but in different amounts, says hydrogeologist Atle Dagestad at the Norwegian Geological Survey (NGU).

“In Norwegian bedrock, groundwater is mostly found in cracks and weak zones, because we don’t have larger areas of sedimentary rocks with primary porosity where the groundwater can flow,” says Dagestad.

The amount of groundwater can be particularly large in weak zones in the bedrock, where bigger tectonic movements lead to the rock being crushed.

Groundwater rarely flows in veins in the subsoil,” says Dagestad. It occurs more in areas where the bedrock consists of limestone.

“In Norway, this kind of bedrock is found in the Svartis area in the north, which is known for its numerous big limestone caves, and where there can occasionally be significant water flow.”

“In sediment deposited by rivers or glaciers from earlier times, some layers have better water flow properties than others. But we don’t find a lot of water veins in Norway,” Dagestad says.

A million dollars

Along with joining water dowsers in the field, Tunstad has observed and arranged tests, where dowsers’ abilities have been tested using scientific methods.

The results have been clear.

“Whenever researchers have systematically gone in, they’ve found that water dowsers don’t have this ability,” Tunstad says.

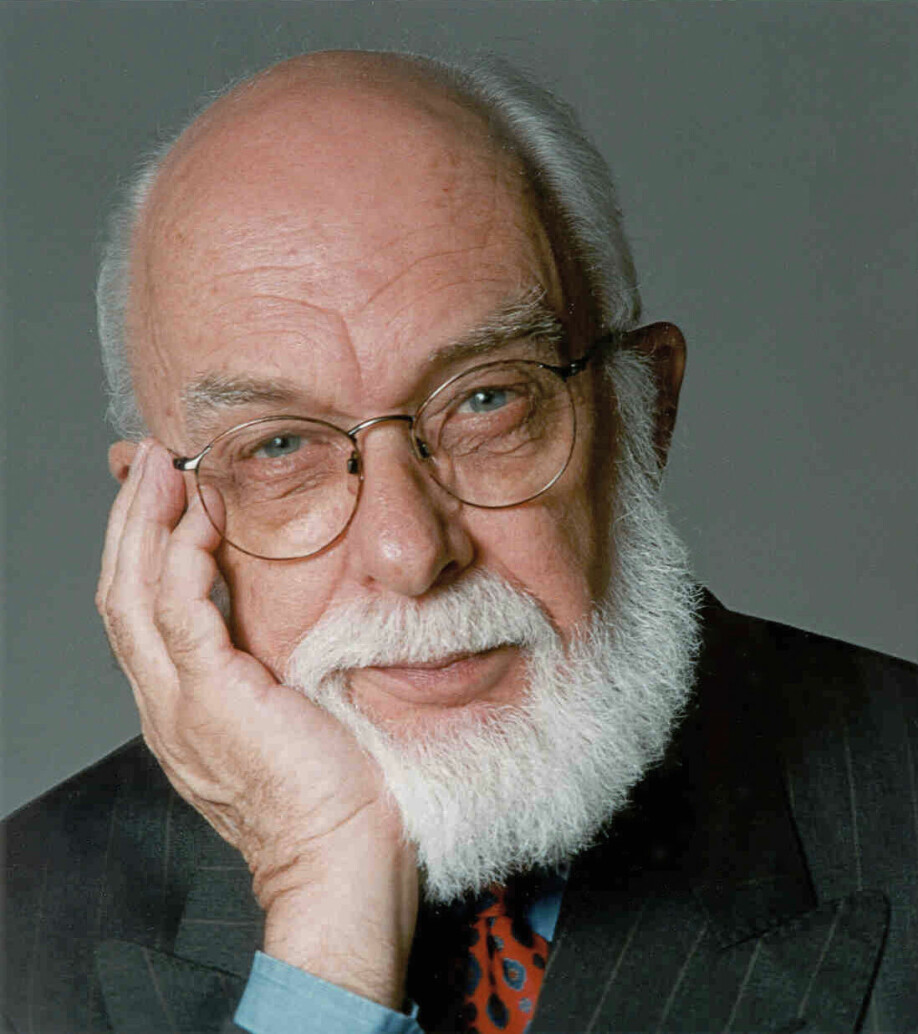

James Randi was a magician, a writer and a sceptic who passed away last year. He is known for launching the One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge. The person who could prove that they have supernatural abilities would receive $10 000. Later, the prize was raised to one million dollars.

Randi’s challenges have included experiments with dowsers. None of them has been able to prove that they have the ability to find water or other objects with dowsing rods.

No better than flipping a coin

Tunstad joined Randi for an experiment in Finland in the 1980s.

“There was a dowser who’d made his living from finding water,” he said.

Now the dowser wanted to test his abilities, and he and Randi agreed on the terms.

“First, Randi set out a container of water. The water dowser could see the water, and when he tested it with his rod, it dipped strongly. No one could say that the rod wasn’t working that day, or that the dowser was in poor shape.”

Next, the water was placed where it wasn’t visible. Containers that either held water or were empty were hidden in boxes. Neither Randi nor any of the other involved parties knew whether the rod was dipping over a full or an empty water container.

“We did this all day long. Only when the results came in were we told that the dowser had only found water around 50 per cent of the time, about the same result as he would have had if he’d flipped a coin,” says Tunstad.

You can watch a video of the experiments arranged by James Randi with dowsers in Australia here.

Mining and treasure hunting

Some people use a pendulum or L-shaped metal rods, instead of a Y-rod or twig to look for the hidden items.

In addition to searching for water, people have used rods to find other things, such as burial sites and metals.

When did dowsing start?

Johannes Dillinger is a professor of early modern history at Oxford Brookes University and has researched the history of the dowsing rod.

He says the dowsing rod appeared in the late Middle Ages in Germany in connection with the mining industry.

The book De re metallica is a textbook on mining from 1556 and is one of the earliest known texts that mention dowsing.

The author, Georgius Agricola, wrote that rods were sometimes used to find mineral veins. But he wasn’t positive about the practice, says Dillinger.

“He rejected the idea, saying it’s below the dignity of a decent miner to use dowsing,” Dillinger said.

Its use became more widespread in the 17th century, then mainly as a tool for finding hidden treasures.

“Treasure hunting was actually the most important use of dowsing rods in the pre-modern period,” Dillinger says.

Water dowsing wasn’t important

The practice was never generally accepted, says Dillinger.

“Certain schools or courses for miners included dowsing in the instruction, but the practice was always very controversial.”

Water dowsing wasn’t important, he says.

“Finding water wasn’t really a problem. Most of Europe has plenty of water. There wasn’t any point in looking for water.”

The use of rods to find water was mentioned early on but did not become widespread until later.

The phenomenon of dowsing has been attributed to three main ideas over time, says Dillinger.

The first explanation is that dowsing was a form of magic. The second is that the dowser is sensitive to what he or she is looking for, and the rod provides a way to focus. The third is that mineral veins, for example, emit something that physically affects the rod.

L-rods used in avalanche search

Few studies exist showing that dowsing actually works. But experiments have been conducted.

A study published in the journal Nature from 1971 was undertaken by the Ministry of Defence in the UK, and found no support that using dowsing rods works. Tests were also carried out to see whether dowsers could find mines and water.

Norwegian researchers Rolf Manne and Steinar Bakkehøi carried out an experiment in 1987. Manne had reacted to the Red Cross promoting the use of forked rods or L-rods to find people who had been buried by avalanches. In 1986, 31 soldiers were caught in an avalanche in Vassdalen in Northern Norway, and 16 perished. Dowsing rods were among the tools used to find them.

The Norwegian Armed Forces invited Manne to take part in a scientific experiment in which a soldier was (safely) buried.

Four dowsers with extensive experience and two teams of quickly trained soldiers tried to find the buried individual. Nobody did.

‘The Armed Forces concluded from this that dowsing is of no value in avalanche searches, and the method was abandoned,’ Manne wrote in the series Psevdovitenskap og etikk (Pseudoscience and Ethics), published by NTNU.

Underground water pipes

In 1991, an experiment was carried out in Kassel, Germany by the German sceptical organization GWUP. Twenty dowsers participated.

A pipe was dug into the ground, with the water supply to the pipe turned either on or off. The participants had to find out whether there was water in the pipe or not with the help of a dowsing rod. The dowsers did 30 tests each.

The results were no better than what you would expect from random guessing. The experiment has not been published in a scientific journal, but was described in an article in the magazine Skeptiker in 1991.

German experiments

A 1995 report written by Hans-Dieter Betz from Germany provided support for the use of dowsing. The company Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) dug wells in arid areas with support from the German authorities. Dowsing was among the approaches they used.

According to Betz, the results from Sri Lanka were particularly impressive, where the dowser found water in over 90 per cent of the cases. He wrote that a success rate of 30 to 50 per cent would be expected based on the geological conditions.

However, controlled experiments that Hans-Dieter Betz helped conduct did not yield the same result.

In the late 1980s, 500 water dowsers underwent tests in Germany. The 43 with the best results were selected for further tests.

The water dowsers were to locate a pipe with running water. The water pipe was on the ground floor of a barn, and the dowsers searched on the second floor.

Of the selected candidates, 37 only attained results that matched random chance. Six had slightly better results, according to Wikipedia. The researchers believed this was proof that the dowsing phenomenon was valid.

Jim T. Enright, a professor of behavioural physiology, did a critical analysis of the experiments.

Enright criticized the researchers’ analysis and believed that the results of the best were also due to chance. According to him, the study was ‘the most convincing disproof imaginable that dowsers can do what they claim.’

Build skills from experience

Hydrogeologist Dagestad believes that individuals who succeed at dowsing can be good at reading the terrain and the local hydrogeological conditions.

“I think they’re good at observing where in the terrain the probability of finding groundwater is good, and over time they gain experience with where to look for water.”

Tunstad concurs and says that the rod might be a tool to help with concentration.

“I would say that their brains are what solve the terrain. That’s been shown through the blind tests. It's not the twig, it's the brain,” he says.

Dagestad adds that most of Norway has a lot of rainfall throughout the year, which makes it less demanding to find groundwater for individual households and smaller water supply facilities.

In the past, it was perhaps useful for a stranger to give advice on where to dig a well, says Dagestad.

“Digging down to the groundwater probably took several days, and it wasn’t completely safe either. If half the village was needed to dig, then they’d be less likely to start arguing among themselves if an outside expert had pointed out a suitable location for a well,” he says.

“The probability of finding water is greater if you dig down a few more metres.”

Rod tips out of equilibrium

Physicist Vistnes says the rod is kept in a state called unstable equilibrium. Small unconscious movements of the hand can cause it to move out of position.

“This means that it only takes very little for the rod to react. It may seem that it dips really strongly. But that power really is only coming from you keeping the rod tense yourself,” says Vistnes.

“If you hold this belief, along with a rod in unstable equilibrium, then what you think and hope can also contribute to these effects.”

“It’s been an interesting journey through this landscape. I have to say that. But I’ve probably ended up without any faith in the dowsing phenomenon,” Vistnes says.

Power of thought has no effect

Tømmerdal, who is a dowser himself, still has no doubt that using a dowsing rod works.

“Of course, scientists are against something they themselves can’t see, touch or measure with their instruments,” he says.

Tømmerdal disagrees with Vistnes that the effects on the rod come from small movements and the way it is held.

“That's just nonsense. There’s no point in controlling or making small unconscious movements to force the rod, in my case, to go up,” says Tømmerdal.

He points out that dowsers clearly look at the terrain, but that’s not the main point.

“When we come across a water vein, water pipes or electrical wires underground, the power of thought doesn’t help,” he says.

“Those of us who know how dowsing works, know that it’s real!”

References:

Arnt Inge Vistnes: Ønskekvistfenomenet – del 1: En personlig beretning om en pussig folketradisjon, Fra fysikkens verden, number 3, 2021.

Arnt Inge Vistnes: Ønskekvistfenomenet – del 2: Rapport fra en vitenskapelig studie, Fra fysikkens verden, number 4, 2021.

Anders Bærheim et.al.: Jordstråler – et begrep uten vitenskapelig grunnlag. Tidsskr Nor Lægeforen, 2006.

Erik Tunstad: Duell ved soloppgang. Skepsis dokument: Søkevinkler, Skepsis, number 3, 1992.

R. A. Foulkes: Dowsing Experiment. Nature, 1971. (Summary)

Rolf Manne: Ønskekvist i snøskred – psevdovitenskap i praksis?. May Thorseth (Red.), Psevdovitenskap og etikk, NTNU, 2005.

Hans-Dieter Betz: Unconventional Water Detection: Field Test of the Dowsing Technique in Dry Zones: Part l. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 1995.

J. T. Enright: Water Dowsing: the Scheunen Experiments. Naturwissenschaften, 1995.

J. T. Enright: Testing Dowsing: The Failure of the Munich Experiments. Skeptical Inquirer, 1999.

H. -D. Betz et.al.: Dowsing reviewed — the effect persists. Naturwissenschaften, 1996.

Robert Konig et.al.: The Kassel Dowsing Test: Part 1. Skeptiker, 1991. republished on Geotech.

Robert Konig et.al.: The Kassel Dowsing Test: Part 2. Skeptiker, 1991. republished on Geotech.

———

Translated by Ingrid Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no