The Placebo Effect:

From mystical magnetism to using our bodies inherent powers

The human body has a remarkable built-in capacity for rectifying its own ailments. “The medical profession should make more use of this,” says Norwegian professor.

Word spread amongst the Parisian upper class in the late 18th century:

A new man in town had a novel cure for pains, paralysis and numerous other maladies.

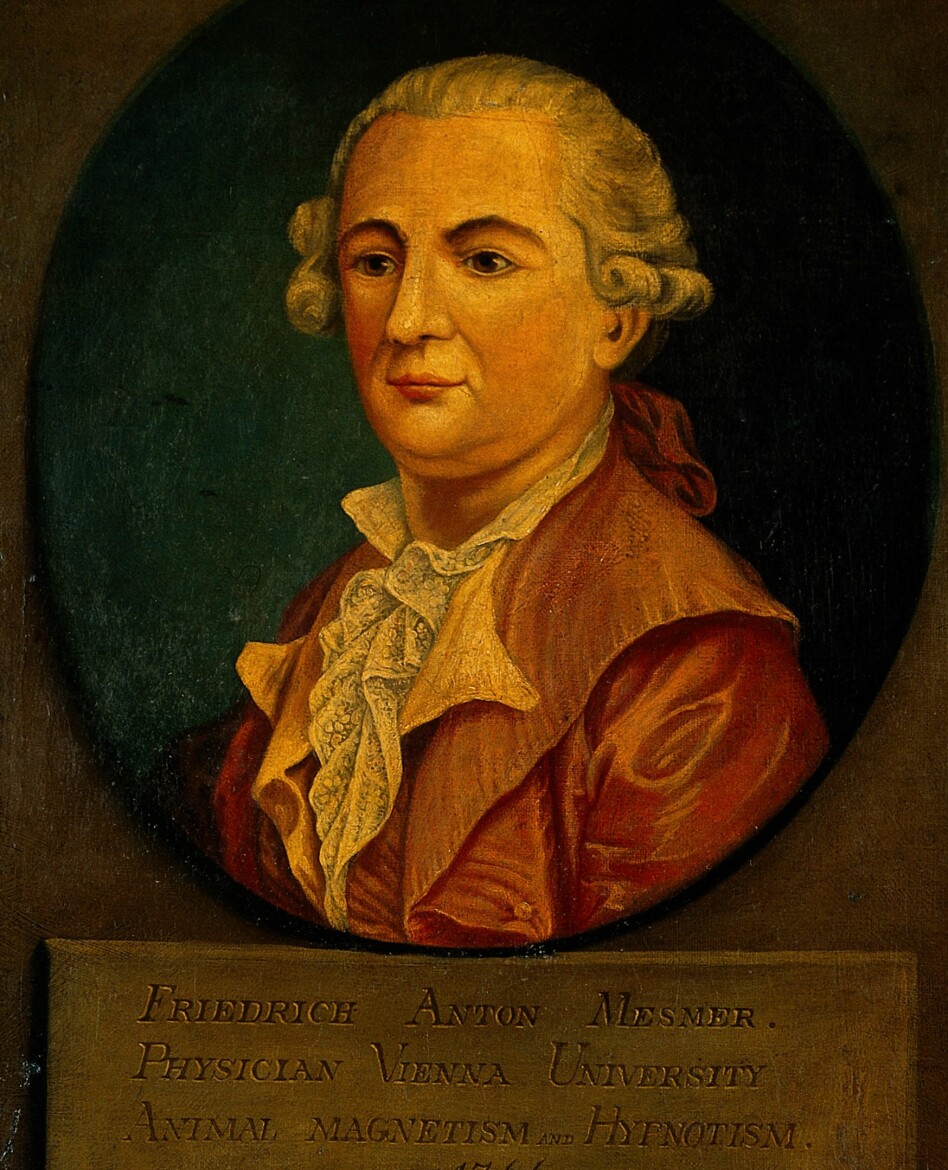

The charismatic German Dr Franz Anton Mesmer had discovered an invisible energy – he called it animal magnetism – allegedly flowing through all living organisms. Obstacles to this flow triggered illnesses. The problem could be corrected with some simple tools or manipulations.

Mesmer claimed that magnets could restore balance and unclog the flow. Later he claimed, conveniently, that he personally had these magnetic powers and could cure patients simply by touching them.

Paris buzzed with tales of patients who had been cured of their ailments. Dr Mesmer’s waiting room became more and more crowded with perfumed customers.

So many people in need of a cure.

And only one Franz Mesmer to go around.

Mesmerized

The overbooked German had to hire assistants and soon he made another timely discovery:

He could wave his hands over water and magnetize it. Mesmer now designed a special barrel for soaking metal rods in “magnetized” water.

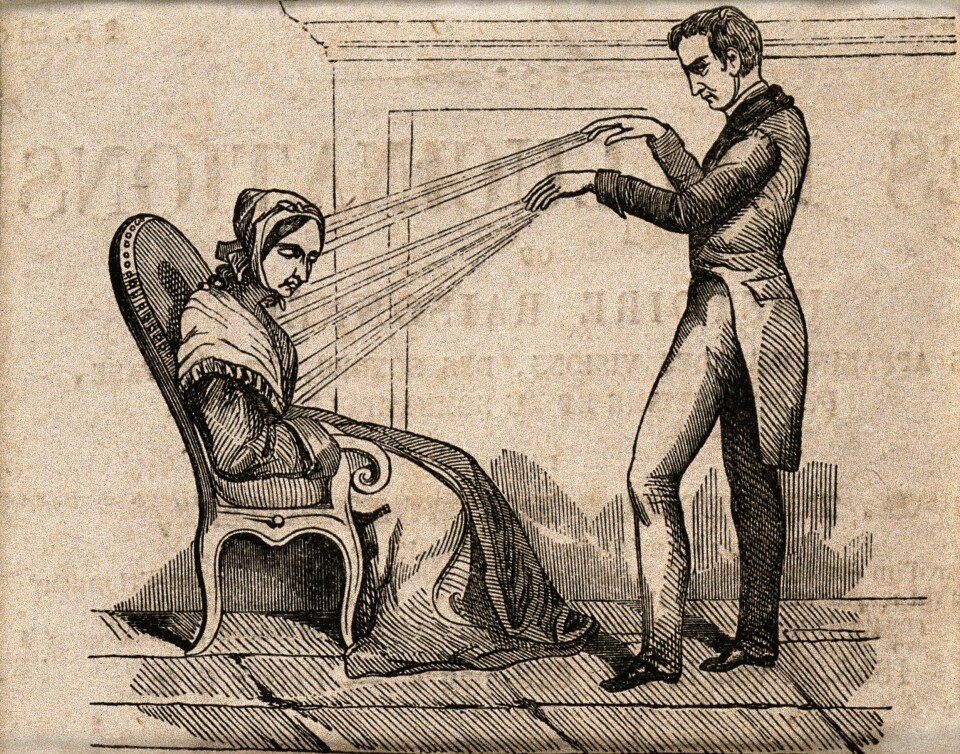

Now patients could sit around the barrel, each in contact with the magnetism via their own metal rod. Mesmer strolled from one patient to the next, passing his hands along their bodies, guiding the animal magnetism to the right places.

The patients – often female, upper bourgeois or aristocratic – exhibited strong reactions. A word cropped up for the phenomenon – they were mesmerized. They would moan, tremble and faint.

And recover their health.

All while the assistant played supernatural resonating music on a glass harp.

Blind study

This was all too good to last.

In Versailles, King Louis XVI got word of the astounding results achieved by Mesmer.

Whether out of the spirit of the Enlightenment, or suspicion that some of Mesmer’s cult of followers could have been revolutionaries, or both, the monarch queried: Does animal magnetism really exist?

Louis got a commission to look into the matter. The group consisted of some of the most renowned scientists of the day. Its leader was none other than Benjamin Franklin, the prodigious inventor, founding father and USA’s Ambassador to France at the time.

Their inquiry turned out to make medical history.

Franklin and his fellow investigators decided that the best way to test whether animal magnetism existed, was by blindfolding the patients, so they could no longer see the hands of those who were treating them.

In other words, they did a scientific blind test.

No magnetism

A variety of blind tests – examinations where patients don’t know what treatment they are receiving – demonstrated that the effect of Mesmer’s treatment in no way could be linked to magnetism. Patients were just as likely to improve from water that had not been “magnetized”. Or there would be no outcome despite ample applications of the prescribed manoeuvres directed toward the patient.

The only factor that seemed to have an impact was what the patients believed. When they thought they were being treated they reacted. If they thought they were not receiving treatment, they would have no reaction. The presence or not of Mesmer's magnetism made no difference.

Science’s first placebo-controlled blind study delivered two important revelations:

Animal magnetism does not seem to exist.

And individuals can in some mysterious way become healthier all on their own if they believe they are receiving effective treatment.

Heads began to roll

Is this some sort of self-deception or conceit?

Even Mesmer’s disciple Charles d’Eslon was convinced by the blind tests that something had to be amiss with the magnetism theory, but he perceived this could be put to use: When properly administered, maybe a patient’s self-deception could become a useful medical procedure?

Perhaps researchers would have dug deeper into that potential if these were not such turbulent times.

Franklin was soon recalled to the USA. The French Revolution overturned the status quo in Paris and Louis XVI and half the Mesmer commission were guillotined. Mesmer’s body stayed connected to his head but had to close shop after word of the commission’s findings got out.

In scientific circles, however, the results opened new territory for medical science.

Troublesome illusion

A seed was sown:

Franklin’s experiments indicated that any beneficial results from treatments could in reality be the effect of a patients belief and imagination.

To find out whether something worked, one had to compare it with an inactive substance or a sham treatment – a placebo.

And this is still the way most of us understand placebos: A rather bothersome illusion which needs to be accounted for in medical research to see whether a remedy really works.

But that’s a big mistake.

In reality the placebo effect is a far cry from a simple self-deception. It can be registered as chemical substances in the body and electric discharges in the brain. In some cases, the placebo effect might be behind the entire impact of an individual’s treatment, even when traditional school medicine is given.

Nevertheless, much of how we can utilize this remarkable capability for the body to heal itself remains a mystery.

From pain to Parkinson’s

The placebo effect has been shown to help in an array of ailments: Chronic pains, anxiety, depression, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, hypertension, Parkinson’s, schizophrenia, allergies, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis, just to name a few.

It even has an effect on afflictions that are often treated surgically.

Some dumbfounding results from a Finnish study were published in NEJM in 2014.

Medical researchers conducted a study on a rather common surgical procedure for knee injuries. Half the patients in the study received a standard meniscus operation. The other patients also had their knees cut and sutured, but the surgeons didn’t really do the procedure, thus changing nothing in the knee.

On average, after a year the patients got better. The recovery rates were the same in both groups. The sham surgery worked as well as the real operation.

In 2018 the same conclusion was made in a comparable study of the world’s most common shoulder operation used for treating the so-called impingement syndrome.

In the same year the medical journal the Lancet hinted that even the effect of angioplasty – the widening of narrow or obstructed veins and arteries – can be attributed to the placebo effect.

But the most fascinating example could be treatments of Parkinson’s Disease.

Suddenly like normal

Parkinson’s is an affliction that arises from the devastation of braincells that produce the neurotransmitter dopamine. Eventually the dopamine deficiency causes progressively stronger symptoms such as muscle stiffness, trembling and mobility impairment.

There is still no medical cure for the disease. But we have treatments which relieve symptoms. One is deep brain stimulation. Doctors surgically install electrodes in the brain area containing the dopamine producing cells.

Electric stimulation gets the cells to create more of this essential chemical messenger. The result can be remarkable: When the current is switched on the patient goes from stiff and mobility impaired to almost normal in just a few minutes.

However, what is really incredible is that the same result can be achieved when the patient just thinks the electricity has been turned on.

“I have seen videos of such patients. It’s pretty dramatic,” says Magne Arve Flaten from the Norwegian universities OsloMet and NTNU. He has researched the placebo effect.

The immediate question is: How could this be possible?

Much remains obscure but there are clues:

This is a matter of expectations but cannot be just self-deception. We know that the body’s medicine chest is involved, and the effect isn’t the same for everyone.

Expectations

In a way, it is self-evident:

A placebo medicine for a headache would have no effect if you didn’t know you took it. The definition of a placebo pill or tablet is, after all, an inert remedy that has no real healing ingredients.

“We need to keep in mind that the placebo effect is not the effect of the placebo – remember that it is an inactive pill. It’s the effect of all the other things,” says Professor Emeritus Arnstein Finset of the University of Oslo (UiO), who has researched the placebo effect.

Or as Ted Kaptchuk of the Harvard Medical School said in his TED-talk in 2015:

“The placebo effect is a way of quantifying and measuring everything that surrounds pills and procedures – mainstream or alternative. They’re about the rituals, the words, the engagements, the costumes, the diplomas and those special things you get when you go to a healer. They’re about how this drama of healthcare alleviates symptoms and changes the courses of diseases even without pharmaceuticals.”

The physician is alpha and omega

So, the expectations that we will get better can actually make it happen. The magnitude of the effect depends on how much expectation the situation actually creates.

The doctor’s role is often key in this respect.

“The research shows that the placebo effect can hinge on communication between the doctor and the patient. It can depend upon which message the doctor conveys, but also on how much of a wallop he or she puts into it. How convincing they are,” says Finset.

Recently a study published in Nature showed that the effect actually depended upon whether the person doing the treatment had faith in the medicine.

When the treatment provider was convinced that the remedy worked, the placebo effect of an otherwise inactive analgesic cream increased. In such cases the patient also perceives the provider to be more empathetic.

“Research has shown that the colour and size of the placebo pills can be significant,” says Finset.

Surprisingly though, the effect does not even depend on deception.

Fear can counter the effect

“Most remarkable are the studies conducted by Ted Kaptchuk from Harvard. He tells the patients straight out that they are getting a placebo and still achieves an effect from the treatment,” says Finset.

Other studies show that negative expectations work in the opposite way. Norwegian studies are among them.

“Peter Lyby’s doctoral thesis showed that fear plays a vital role. The placebo effect is zeroed out if the patient is scared,” says Finset.

Another Norwegian study showed that low confidence in the effect of treatment can actually eliminate the effect of bona fide pharmaceuticals, explains Magne Arve Flaten from OsloMet and NTNU.

The participants in a test were told the cream they would be using was just an ordinary salve without any pain-relieving effect. These subjects then failed to experience any analgesic effect even though they had been given a potent local anaesthetic salve.

Experience decides the effect

Another important factor involves a person’s baggage, the experiences one has from before, explains Flaten.

If you have previously found paracetamol to relieve your headaches, you are more likely to get the placebo effect when you think you are swallowing this substance. Or such expectations heightened the effect of the next real tablet.

In this way the impact you get from most medicines is a mix of the placebo effect and the real effect.

“The placebo effect accounts for some of nearly all treatment,” says Flaten.

For a few ailments, such as migraines, the placebo effect comprises most of the clout of the medications. This is well documented.

Much more uncertain, however, is the way in which expectations can play out as an effect in the body.

The body’s medicine cabinet

When Ben Franklin and his 18th century associates revealed the truth behind the miracle treatments of Franz Mesmer, they concluded that the effect had to be caused by self-deception. It was merely what we would now call a psychological effect.

But that doesn’t look to be the case.

Of course, the outcome does involve psychology. It doesn’t work on people in a coma or who suffer serious dementia. But it is not about ignoring pain, pulling oneself together mentally or shrugging off an imaginary affliction.

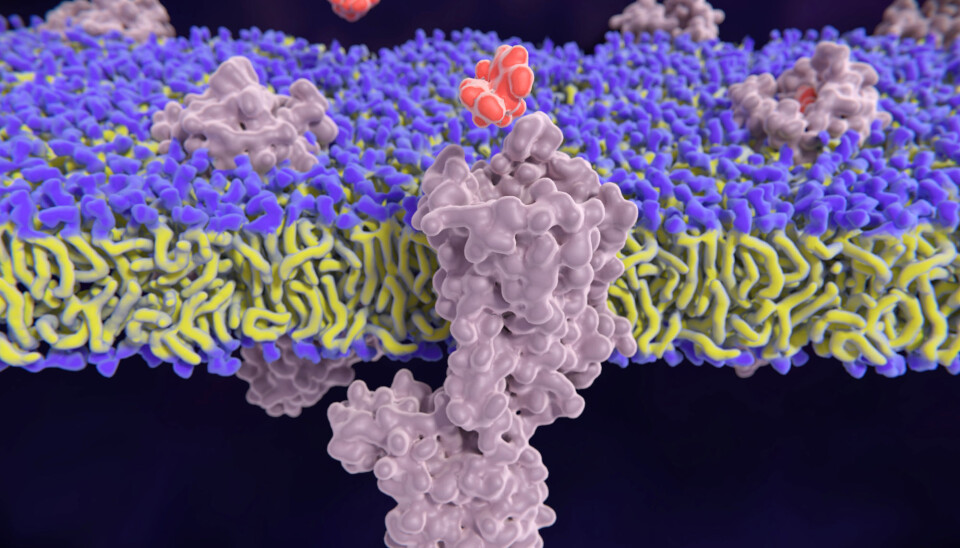

In recent decades research has shown the placebo effect to be truly creating biological changes in the body. Can expectations somehow open the door to the body’s own medicine cabinet?

The living mass of cells, tissue and organs that comprise us all really do have an amazing arsenal of medications available.

For instance, they generate opioid-like substances which alleviate pain. They produce cannabis-like endocannabinoids which control the feeling of well-being. And they provide the dopamine which impacts both mobility and the sensation of pain.

Opioids in the veins

“An attention-grabbing study comes from Fabrizio Benedetti of the University of Torino in Italy,” says Finset from UiO.

The Italian asked the question: Can placebo treatment for pain trigger the body’s opioids, which give the same effect as morphine and similar medications?

Benedetti initiated a clever experiment to test whether this was one of the mechanisms behind the placebo effect.

The researcher administered pain to the subjects under experimental conditions. Then he told ten of the participants that they were receiving a painkiller, but they actually did not receive it. The result was – as the reader would now guess – that the participants reported an alleviation of the pain.

But then came the real test:

In the middle of the experiment some of these same placebo participants received a so-called opioid antagonist, a substance that blocks receptors and makes the body insensitive to opioids.

The results were overwhelming: The group that was given the opioid antagonist started to report returns of the pain. They lost all the effects of the placebo treatment. Thus, there is good reason to conclude that the pain-relieving effect of placebo treatment links to the body secreting natural opioids.

And here we have a connection with expectations, explains Finset.

“Structures are found centrally in the brain which are activated by positive expectations and this also is important for natural opioids,” he says.

Dopamine and stress reduction

The body’s own medications apply also when it comes to Parkinson’s.

The electrodes used in deep brain stimulation make brain cells produce dopamine, which the patients lack. The same occurs when the patient experiences the placebo effect.

But what about the placebo effect in sham surgical procedures?

Maybe it relates to temporary pain relief, enabling the patient to more easily use his or her knee or shoulder?

We don’t have all the answers. Several mechanisms might be at work simultaneously.

Professor Per Aslaksen of UiT, The Arctic University of Norway, which has also researched the placebo effect, thinks stress can factor in for some people.

“The more negative stress a patient experiences, the greater the response will be on a treatment provider who triggers positive expectations,” he says.

Flaten of OsloMet and NTNU concurs: “Stress is linked to increased pain and discomfort. If something inhibits stress it also reduces pain,” he says.

But there are sizable individual differences in this respect. Not everyone responds to all types of placebos and some people experience a much greater effect than others.

In recent years studies have indicated that our genetic makeup can be involved.

Alternative treatment

No matter what future research might bring, there is little doubt that doctors and other health personnel have access to two tools for helping patients:

The first is medications and medical techniques with documented effects.

And then there is this other thing.

What complicates the issue is that doctors are not the only ones to have access to the placebo effect.

Aslaksen, Flaten and Finset all believe that the placebo effect is what makes people feel the effect of alternative treatment.

While nothing indicates that things like spinning crystals or suction-cupping have any effect, the alternative treatment provider can still trigger the placebo effect.

This could be the reason why so many people go for alternative treatment despite the fact that research of many types of complementary medicine has turned up disappointing results, says Flaten.

He thinks the medical profession should on the whole become more aware of the effect of positive expectations.

The MD can impair the effect

Doctors differ. Some instil a sense of security, but others are less competent in this respect. Doctors who curb stress and raise patients’ positive expectations are going to make medications work better because the benefit of the placebo effect adds to the pharmaceutical effect.

Conversely, a doctor can weaken the effect of a beneficial treatment by provoking negative expectations and making patients insecure.

So, a situation can occur wherein a patient fails to improve after seeing a doctor even though he or she gets sound medical treatment. The same patient might enjoy good results from an alternative practitioner who has no actual effective treatment but is adept at triggering the placebo effect.

Contrary to MDs, the alternative practitioners often have more time for a patient. They might use anything from dangling crystals to enemas. The more extraordinary the experience the greater the placebo effect, according to some research.

More show is not the answer

Nevertheless, Aslaksen of UiT does not think established scientific medical practice needs to put on a bigger show.

“The placebo effect occurs when doctors are good at creating positive expectations. It’s a matter of really connecting with the patient, not putting on an act,” he says.

“The medical profession should make more use of this.”

Assumedly, we have yet to unleash the full potential of this effect of expectations. And we are far from a complete understanding of the placebo effect.

We haven’t really touched on the deepest issue.

If the body has a built-in potential to heal itself – why does it wait to use this until a doctor or a shaman turns up?

Why are we dependent on these social interactions with other people to get the process started?

“I have wondered about that myself,” says Flaten of NTNU.

That question awaits an answer.

Translated by: Glenn Ostling

———