What exactly is a personality disorder?

Up to 14 per cent of the population is affected.

There are 10 different types.

But what exactly is a personality disorder, and what does it mean to receive such a diagnosis?

“If I were to put it simply, a personality disorder is a mental disorder where persistent struggles with oneself and with others create problems in everyday life,” Ingeborg Ulltveit-Moe Eikenæs tells sciencenorway.no.

She is head of the National Competency Service for Personality Psychiatry (NAPP).

“It is a mental disorder where low and/or unstable self-esteem and difficulties in interpersonal relationships negatively affect quality of life and daily functioning,” she says.

In 2021, Ulf Andersen, the chief statistician at the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV), estimated that 28,000 disability benefit recipients have personality disorders.

Genetics or shaped by experiences?

Most people who develop a personality disorder do so in adolescence as a combination of genetic vulnerability and environmental stress during their upbringing. If you are more vulnerable, you tolerate negative experiences less than those with less vulnerable genes.

What you experience growing up can therefore have significant consequences because it occurs while your personality is developing. It can involve various types of neglect, abuse, or trauma.

“It is extremely rare for a personality disorder to develop in late adulthood,” Eikenæs says.

Diagnosing the disorder

To receive a diagnosis, the practitioner must first exclude other disorders such as anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance use disorders, or ADHD.

Once that is done, the assessment for personality disorder begins. The diagnosis is made through a comprehensive evaluation that typically includes an interview and questionnaire.

“We need to see that there is something relatively stable and typical for that person over time to be able to say that this is a personality disorder and that it is not better explained by another mental or physical disorder,” Eikenæs says.

Different ways of understanding personality disorders

There are different ways to understand and diagnose personality disorders.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is the World Health Organization's diagnostic system, which Norway is obliged to follow. Currently, Norway uses ICD-10, the tenth version. The Norwegian Directorate of e-health has begun the process of transitioning to the new version called ICD-11.

“There is currently no set date for the introduction of ICD-11 in Norway, and it has not yet been translated into Norwegian,” Alfhild Stokke writes in an email to sciencenorway.no. She is the department director at the Norwegian Directorate of e-health and is responsible for health classification codes and terminology.

ICD-11 is radically different from ICD-10 when it comes to personality disorders but is quite similar to the alternative model introduced in DSM-5 in 2013, according to Ingeborg Ulltveit-Moe Eikenæs. DSM is the American diagnostic system.

“I really like the alternative model because it clearly states what it's all about. It makes it much easier to understand what personality disorders are,” Eikenæs says. “We have an ongoing research project where we are testing this model in Norway, and the patients feel understood – ‘this is exactly what it's about’, they often say.”

Personality functioning

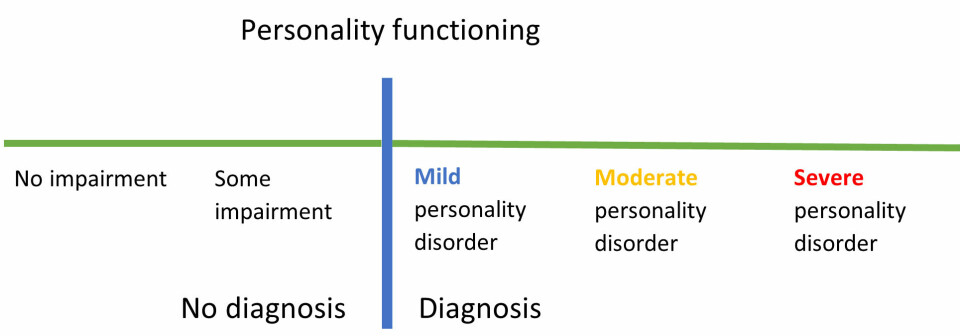

“Personality functioning is a term that is increasingly used and has a central place in the alternative model,” Eikenæs says.

According to the alternative model, personality functioning is measured along two main components: functioning in relation to oneself and in relation to others, with four main domains: identity and self-direction, empathy and intimacy. To reach the diagnostic threshold in the alternative model, there should be moderate problems in at least two of the four main areas.

But personality functioning is not something that only applies to patients. It applies to all people.

“This means that personality problems are something that we all have to a greater or lesser extent. If you have a lot of it, then you have a personality disorder,” she says.

Eikenæs believes that this way of thinking and talking about it can help change stigma and negative attitudes.

“Because then it's not just them and us, or me and them, but something that everyone can experience to a greater or lesser degree,” she says.

The diagnosis may be considered taboo

Eikenæs says that many people have judgmental attitudes towards conditions like narcissistic personality disorder.

“They are often labeled as simply evil and cunning. In reality, they struggle severely with their self-esteem – they are often torn between self-contempt and excessive self-esteem, and conflicting emotions such as shame and pride,” Eikenæs says.

Individuals with avoidant personality disorder also struggle with regulating their self-esteem. The difference is that they consistently have negative thoughts about themselves and have less of the fluctuation that those with narcissistic personality disorder struggle with, she explains.

These diagnoses are being phased out, i.e., narcissistic, emotionally unstable (borderline), and avoidant.

“In the future, we may talk about a mild/moderate/severe personality disorder with specific traits. Avoidant traits, or impulsive traits, for example. Then we might use trait profiles to specify the type of personality problems involved,” she says.

ICD-11 has actually eliminated all the categories. Only borderline is temporarily retained. The alternative model introduced in DSM-5 has kept 6 out of 10 categories.

“There may be some challenges when we implement ICD-11,” Eikenæs says.

Not everyone receives treatment

Those who seek treatment for their personality disorder may encounter several problems.

“It's like playing the lottery. It is highly dependent on where you live in the country whether you are offered effective treatment,” Eivind Normann-Eide said in a 2021 forskning.no article (link in Norwegian).

He is a specialist in psychology at NAPP.

Eikenæs adds that it can also be difficult to receive treatment after the age of 30. Many specialised treatment programmes include young people up to the age of 30. If someone receives such a diagnosis later in life, it can be even more challenging to get help.

And if treatment is offered, it may not be specifically tailored to personality disorders. Many describe it as an endless treatment process. They receive treatment for anxiety or depression but not for the underlying issues. This often leads to relapses and further rounds of treatment, the researcher explains.

“It is challenging to undergo treatment, and patients can become disillusioned and unmotivated if relapses occur repeatedly,” she says.

But there is hope for recovery

Long-term studies show that almost 9 out of 10 individuals no longer meet the criteria for the diagnosis after 10 years, according to Helsenorge (link in Norwegian).

“The actual diagnoses are not as stable as previously thought. However, newer research shows that personality traits are more stable. This means that having a personality disorder does not necessarily mean you will have it forever,” Eikenæs says.

The best approach is to seek help early, as the prognosis is better, and the intervention does not have to be as extensive. This is best for the individual, those around them, and for our society, according to the researcher.

However, the treatment depends on the type of personality disorder in question.

“What we have good evidence for is the treatment of emotionally unstable/borderline personality disorder. It is by far the most researched personality disorder, and several effective treatment methods have been developed. This means that many people receive effective help and experience a significant improvement in their quality of life and functioning,” she says.

The majority of individuals with a personality disorder do not have emotionally unstable personality disorder. Only about one per cent of the population has that specific type, while up to four per cent have an avoidant personality disorder.

“We have much less documentation on what helps in those cases,” Eikenæs says.

She explains that in Norway today, there are many places where they are experimenting with different methods for treating avoidant personality disorder since there is no definitive solution yet. The same applies to antisocial and narcissistic personality disorders. Internationally, there is also little research in these areas.

“It can be challenging for next of kin”

“The most important thing for those around you to understand is that nobody chooses to have a personality disorder. It's a condition that you absolutely do not want, but usually cannot overcome without support and help,” Eikenæs says.

She believes it is important for family members to receive guidance. Currently, there are few places in Norway where such support is available.

“A lot of unnecessary conflicts stem from misunderstandings. When we have strong emotions, our ability to mentalise decreases, and any mentalization impairment becomes more evident. In interaction with those closest to you, unfortunate patterns can develop that are difficult to break free from. It can be challenging for them to understand what is going on,” Eikenæs says.

It is crucial to have an open and non-judgmental attitude to resolve such misunderstandings and conflicts. For example, asking questions like: How did this look from your perspective? What happened inside you when I said or did this?

"The person who is struggling often understands little about what is happening inside the other person, so family members and friends should also be allowed to explain themselves. It is important that it goes both ways,” Eikenæs concludes.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no