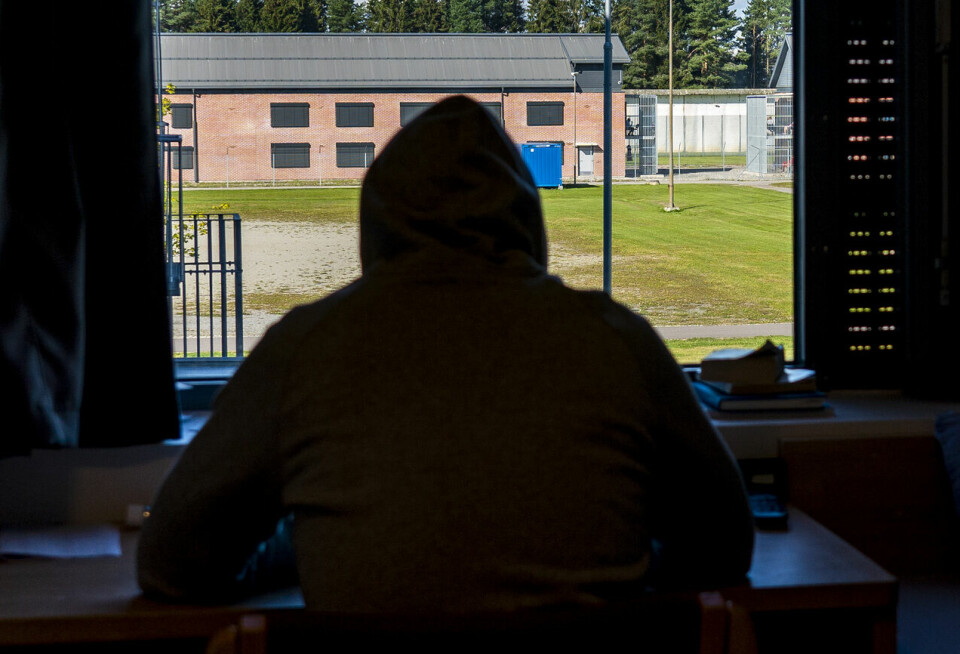

Many inmates have mental health problems

Although the incarceration rate has decreased, the prevalence of people entering prison with a diagnosed substance use disorder or mental health problem has increased over time.

The main reason why the proportion of inmates with mental health problems is on the rise, according to Anne Bukten, is probably that more convicts are allowed to serve their sentences outside prison than before. Bukten is one of the researchers behind a new study.

A prisoner must meet several criteria in order to serve time with an electronic ankle monitor, such as having a place to live, and either a job or studies to attend.

“To put it bluntly, we find fewer well-off individuals arrested for driving drunk in prison today than we did in the past,” says Bukten.

She points out that prisoners with substance use disorder or mental health problems are less likely to meet the criteria for alternative sentencing than the rest of the population.

The consequence of this is that the proportion of prison inmates with such problems has increased.

What the researchers found

In the new study, researchers at the Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research (SERAF) have compared figures from Norwegian health registries between 2010 and 2019.

From 2010 to 2019, the prevalence of diagnosed mental health problems increased from 30.1 per cent to 40.1 per cent among those incarcerated in Norwegian prisons.

The prevalence of substance use disorder increased from 23.6 per cent to 33 per cent in the same period.

The proportion of inmates diagnosed with both a substance use disorder and another mental health problem increased from 6.4 per cent in 2010 to 11.5 per cent in 2019.

The researchers have also compared figures from health registries in Sweden between 2010 and 2013, and from Denmark between 2010 and 2018. In both countries, the trend was the same.

Good access to healthcare is critical

Bukten considers it a positive development that fewer convicts will have to serve time in prison than before.

However, she is concerned that with a different group of incarcerated individuals, the prisons will need to adapt. They need to ensure adequate healthcare services and an environment that minimises harm. There must also be enough staff at work.

“Prisoners have the right to good access to healthcare and to be in an environment that limits the damage caused by a stay in prison,” says Bukten.

This study did not investigate what the situation is like for these groups in Norwegian prisons. But Bukten points to several other studies indicating that inmates with mental health problems face inadequate conditions.

Prison environment is negatively affected

The report from one such investigation was presented by the Norwegian Parliamentary Ombud in 2023 (link in Norwegian), which assessed prisons' efforts to prevent suicide.

According to the report, there are significant shortcomings in the work being done.

Bukten also points to a 2023 inspection report from the Ombud, which reviewed the conditions at Bredtveit Prison and the Zulu East wing at Ullersmo Prison.

“The descriptions of the conditions at Bredtveit indicate that when some inmates are very ill, much of the staff's resources and attention is directed towards the individuals in crisis. This is both important and right, but it means that other inmates end up more isolated as a result of fewer available staff,” she says.

In the report, the Ombud writes that their visit revealed that inmates were "living under critical and even life-threatening conditions." The prison recorded a tenfold increase in the number of self-harm incidents involving 14 inmates between 2018 and 2022.

Significantly fewer staff

Karianne Hammer worked as a prison officer until 2018. She is now a senior adviser at the University College of Norwegian Correctional Service (KRUS).

She confirms that what has emerged in the new study from SERAF is consistent with how the employees experience the situation in Norwegian prisons.

“It’s quite clear that many of the inmates who are well-off have transitioned to alternative sentencing methods. They often acted as stabilisers among inmates who are less well-functioning, and they have calmed down or prevented incidents. Many carry burdens from their upbringing, making their prison experience particularly challenging and burdensome, ” Hammer says.

She also confirms the lack of staffing in Norwegian prisons, and in her opinion, the staffing situation clearly worsened due to the 2015 ABE Reform for reducing bureaucracy and improving efficiency.

“The number of staff has significantly decreased, while the need to monitor more individuals has increased due to higher illness rates. The consequence is that the few resources available have to be used to put out fires,” she says.

The ABE Reform led to annual budget cuts of at least 0.5 per cent for all state enterprises by the previous government.

Hammer notes that the current government has recently increased funding in the latest budget. For the situation to become acceptable in the Norwegian prisons, even more money for staffing is needed, she argues.

Better training needed

Hammer also believes that better mental health training is needed for those who work in prisons.

“We’ve had good staffing in the past, but we haven’t been very good at dealing with mental health problems,” she says.

“In the education for prison officers, there has been a very strong focus on diagnoses, but knowing about diagnoses doesn't help if you don't know how to interact with those who have the diagnoses. Diagnoses are also confidential for correctional staff. The most important thing to know is how to meet individuals who show signs of mental health problems."

Hammer also believes that the laws regulating which sanctions and control measures can be used must be changed, and that the current legislation allows for measures that breach human rights.

She points out that Norway has lost several cases regarding such measures, where it has been concluded that human rights have been violated.

Reference:

Bukten et al. The prevalence and comorbidity of mental health and substance use disorders in Scandinavian prisons 2010–2019: a multi-national register study, BMC Psychiatry, vol. 24, 2024. DOI: 10.1186/s12888-024-05540-6

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no