Almost half of us belong to the working class. But workers have become more invisible, researchers say

Norwegian social scientists have given the workers a voice.

Monday 08 March 2021 - 07:54

The media hardly ever writes about them. And when they do, it’s often with a negative spin.

In popular culture, workers are often portrayed as "simple" and “laughable.”

Very few politicians and others in the upper echelons of society represent them. A lot of workers don’t identify with power, and they experience that they have little power themselves.

Workers often become alienated and politically passive.

In Norway, their occupations are ranked low on the prestige ladder.

Is the working class striking back?

Twenty-seven social scientists have contributed to the Norwegian book Arbeiderklassen (The working class), from which these analyses are drawn.

The working class has long been practically forgotten by researchers.

But now academic interest is on the rise.

Brexit and Donald Trump's victory in the presidential election in 2016 are part of the reason, says Marianne Nordli Hansen, one of the book’s editors, at an event last week.

“People saw that this was a social group that researchers had had little interest in, and that workers were now striking back,” Hansen says.

More than man, manure and metal

Norwegian social scientists interviewed people in various working professions in Norway for the book. They were looking to find out if any of the political power that the working class once had remains.

Some have gone further than just doing an interview.

Julia Orupabo, a researcher at the Institute of Social Research, is one of the researchers who contributed to the book.

For almost six weeks she worked as a volunteer in two nursing homes. She did this to try to see the world from the vantage point of a group that has rarely been researched – that of health care workers.

“When we think about the working class, we often think of male industrial workers – man, manure and metal. We know less about skilled workers who work in female-dominated professions,” she says.

The number of industrial workers has decreased.

But that doesn’t mean that the working class is gone, according to the editors of the book, Hansen and Jørn Ljunggren.

It’s just become more diverse.

Many workers are first- or second-generation immigrants.

And many of them are employed as care workers. These are the people Orupabo has met.

At the bottom of the social ladder

Two other social scientists, Håvard Helland and Ljunggren, have analysed the status of 34 professions in Norway.

The study is based on a large survey on status and trust in the Norwegian population.

Doctors, judges, professors, lawyers and engineers are at the top of the social ladder.

At the bottom are cleaners, taxi drivers, shop employees, postmen, day care assistants and hairdressers.

The answers undoubtedly show that working class occupations hold a lower status than other jobs in Norway’s so-called egalitarian society. This largely coincides with what researchers find in other countries.

In recent years, a great deal of political attention has been paid to the importance of vocational topics. Yet, the researchers in this analysis show that people who have occupations requiring higher education and students who want to do such jobs give the vocational occupations very low ranking on the status ladder.

The researcher found no indication that vocational subjects gained any increased status.

Don’t feel recognized

“The established understanding is that different jobs have different status, despite the fact that we’re concerned with equality in Norway,” says Sabina Tica.

Tica is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology and Human Geography at the University of Oslo and has studied occupational groups that are low in the status hierarchy, specifically hairdressers and shop employees.

When Tica asks them how they think the rest of society ranks their jobs, they place themselves quite far down this hierarchy.

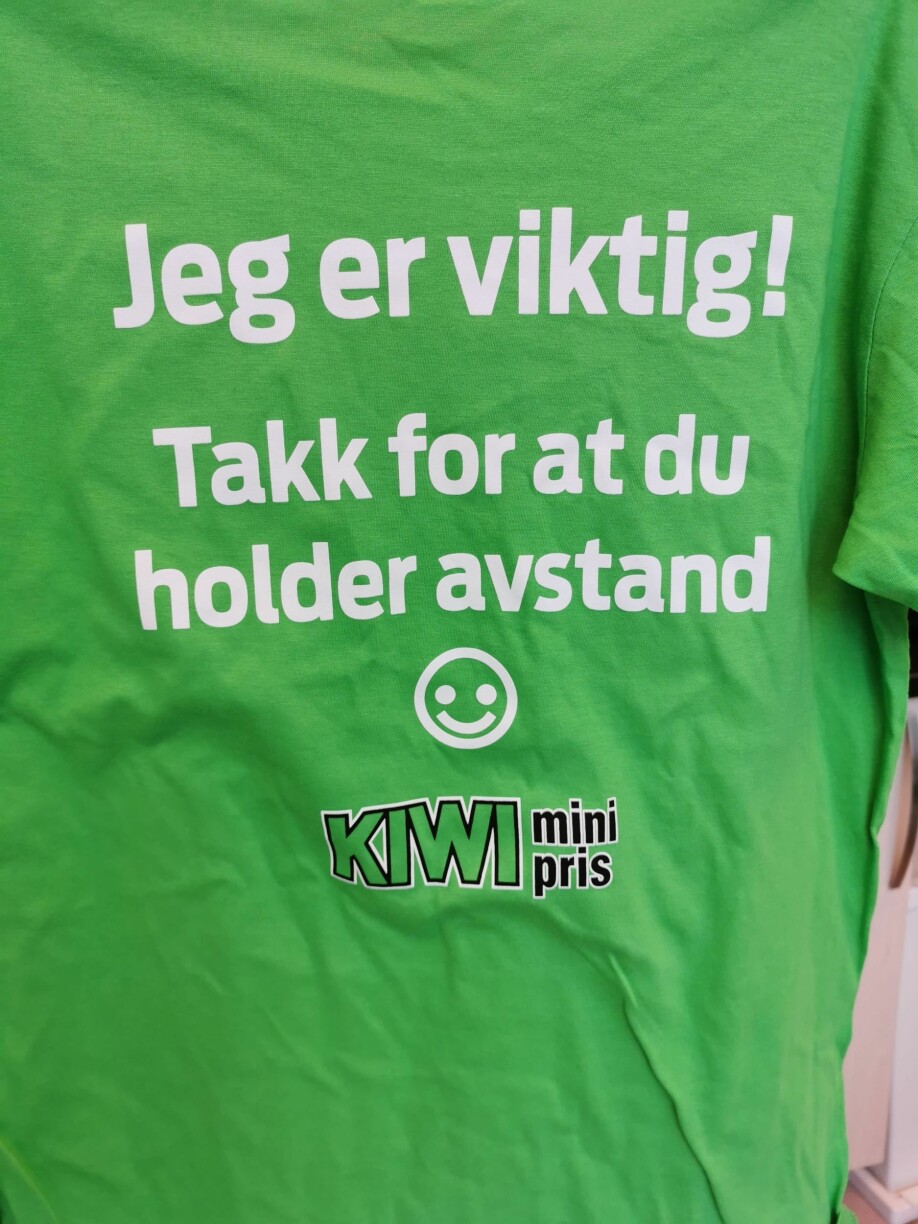

“When we talked about how it should be, they highlight other status criteria and place themselves higher on the ladder. They emphasize the value of their jobs and that they’re competent people who do an important job for society,” she says.

But they don’t necessarily feel that they get that much recognition from society for the work they do, says Tica.

Customer contact is rewarding

Yet store employees and hairdressers still find the customer contact very rewarding in everyday life.

“They highlight their workplace as an important social arena that means a lot, especially for people who are a little lonely,” says Tica.

This is particularly pronounced in more rural areas. There, hairdressers and store employees experience having more customer contact than in the cities, where efficiency is more of a priority.

By emphasizing the carer aspect of their profession, they find pride in what they do, Tica believes.

One hairdresser says:

"I think it's a very exciting job, really. I talked to someone in town, and she said that a hair appointment should be something you could get a blue (reimbursable) prescription for. Because you can come here and get yourself fixed up and stuff and then you feel much better. So I would say I do have professional pride, because you can have such an impact on a lot of people's lives.”

Invisible health professionals

By spending time with health professionals over time, Orupabo managed to capture some of their everyday experiences and small details that aren’t so easily conveyed through interviews.

She experienced a lot of what she saw in the everyday work of nursing home life as frustrating and painful.

“To a great extent I experienced that the voice of the health care workers, the people who work most closely with the elderly, wasn’t heard by nurses and doctors,” says Orupabo.

In a field note from the study, she wrote about the overlap from day shift to evening shift. She observed that only the nurses talked to each other.

"…they look only at each other and their bodies are turned away from the health care workers and assistants. Only when the nurses are finished and the meeting is coming to an end do they look at the others and ask if they have anything to add. If a health care worker takes the floor, it’s usually too late. The concentration and calm that characterized the meeting is over. Nobody listens.”

Big differences

Orupabo thinks it’s too easy to look at the working class as one homogeneous group.

There are big differences within this group, and they have different possibilities for forming a force against those farther up the hierarchy.

Some of the health care workers she studied protested loudly, clearly stating when they found demands to be unreasonable or that important needs of the residents were not listened to.

But the majority didn’t, she believes.

“The staff who raised their voices were primarily carers who had safer positions at work. They either had a majority background or were descendants of immigrants.

But the ones who spoke up weren’t heard either. They were often ignored and to some extent also sanctioned, she says.

Backroom resistance

Several researchers have claimed that the time of the workers' struggle is over and that the new working life has created obedient workers who just comply.

Orupabo experienced something different.

Even staff members who didn’t dare to speak out found ways to resist – in secret.

They tried to gain control of their everyday lives through what the researcher calls “everyday resistance.”

For example, they might throw away dirty cloths instead of washing them. They don’t log everything the manager tells them to. They sneak out for a smoke.

“This backroom resistance, the kind that isn’t punished because management doesn’t see it, contributes to creating a little bit of space in a highly regulated and detail-controlled workplace,” she says.

“Even if the resistance doesn’t change their work conditions, it helps make everyday life a little more liveable. It creates spaces where they can define their own rules and makes the job a little less stressful.”

Many part-time employees

At the nursing homes where Orupabo worked, many of the positions were very part-time and the part-time staff were juggling two or three positions at a time.

Some first-time immigrants also had their contract linked to their residence permit.

“That creates completely different conditions for offering resistance. Immigrants aren’t being passive because of their culture and values, but because their working terms are completely different,” she says.

Left with a feeling of frustration

Orupabo says she was left with a sense of frustration following her weeks in the nursing homes.

She believes all the silent, small details of care disappear when health care workers are made so invisible.

“Examples might be taking time for the small important details like telling a patient what will happen before performing an operation, or closing the curtains when you do personal care for a patient.

The combination of lack of time, low workplace connection and the invisibility of their professional role, creates poor conditions for health workers’ autonomy and competence.

It also provides poor conditions for their ability to follow up individual patients, Orupabo says.

She believes that capable workers aren’t able to stay in this kind of situation for very long. They’ll look for other work opportunities – and the health service thereby loses valuable competence.

But many health care workers have no choice. They just have to stick it out and carry on with their everyday resistance.

Translated by: Ingrid Nuse.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no.

Source:

Jørn Ljunggren and Marianne Nordli Hansen (eds.): Arbeiderklassen [The working class], Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2021.