Your placenta may reveal risk of getting preeclampsia

How much a placenta weighs can indicate the risk for illness in future pregnancies, according to new research.

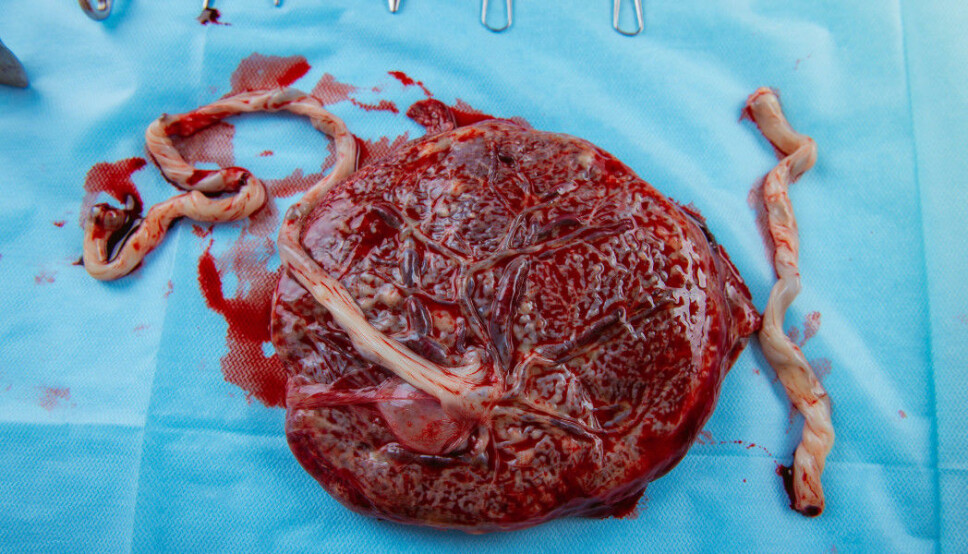

The placenta supplies oxygen and nourishment to the foetus during pregnancy and transports waste materials. A well-functioning placenta is essential for a successful pregnancy.

How the placenta grows can give us a clue as to how the foetus has fared in the uterus. But the growth can also have consequences for the mother's future health.

Doctor Sandra Larsen at Akershus University Hospital (Ahus) has done research on the relationship between the weight of the placenta and the risk conditions among Norwegian women who have given birth. She recently took her doctorate on the topic.

Placenta can warn of a dangerous condition

Larsen’s findings include a new link between the weight of the placenta and the risk of preeclampsia.

This is a condition that can be serious for mother and child. Often, the only solution is to remove the baby from the womb early, either by inducing the birth or performing a Caesarean.

The cause of preeclampsia is not fully understood. But scientists believe the problem may start in the placenta. With preeclampsia, the placenta doesn’t grow properly, and the baby may not get enough nutrition.

A sick placenta can cause a mother's blood pressure to rise.

Larsen found out that the size of the placenta may also indicate an increased risk of preeclampsia in future pregnancies.

Big or small placenta increases foetal death risk

Larsen and her colleagues used data from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway to find connections between the size of the placenta and any health problems.

The researchers compared the birth weight of the children and the weight of the placenta, as well as whether the women had preeclampsia in their first or later pregnancies.

“The weight of the placenta in relation to the child's weight is probably as interesting as the size of the placenta in isolation,” says Larsen.

Previous research has shown that disparities between a baby’s birth weight and the placenta increase the risk of something going wrong.

“A placenta that is smaller or larger than normal in relation to the child's birth weight increases the risk of foetal death,” Larsen says.

Early smoking cessation results in normal placenta

Larsen has also investigated the relationship between placenta weight and smoking in pregnancy.

Children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy often have lower birth weights than other children.

This may be because pregnant smokers are more prone to having a small placenta and little oxygen in the mother's blood. This can prevent the foetus from getting enough oxygen and nutrition.

In women who smoked throughout pregnancy, each cigarette smoked impacted the child's birth weight. The placental weight and the child's birth weight decreased the more cigarettes the mother smoked daily.

But Larsen made a happy finding: women who quit smoking after the first trimester had children with about the same birth weight as non-smoking mothers.

“This is good news and shows that it is very effective to stop smoking at the beginning of pregnancy,” says Larsen.

The placental weight in these women was actually higher than in non-smokers.

Both large and small placenta can pose a risk

A big placenta isn't necessarily just a good thing. The one exception is if both the placenta and the baby are large.

However, when the baby is small and the placenta is large, this may be a sign of poor conditions in the uterus.

“We know that a large placenta relative to the child’s size may indicate that the child was exposed to a harmful environment during pregnancy,” says Larsen.

She explains that the placenta may have grown to try to compensate for poor conditions early in pregnancy.

A low blood percentage in the mother, the number of cigarettes that the mother smoked daily and early smoking cessation can cause the placenta to become relatively heavy in relation to the child's birth weight.

This scenario can lead to serious health problems later in life.

What is a normal placenta?

But what constitutes a big or small placenta? Even women who have given birth likely don’t have the slightest clue.

“We divided the placentas into five weight groups, where the normal weight in the middle averaged between 600 and 650 grams,” says Larsen.

Placentas weighing less than 400 grams were considered small, and those over 800 grams were considered large.

The ideal ratio between the child's birth weight and the weight of the placenta is equivalent to a birth weight of 3500 grams and a placental weight of 600-650 grams.

Small placenta increases risk of dangerous condition

The cause of preeclampsia is unknown, and it is difficult to predict which women will be affected.

But Larsen made an important discovery. Mothers who had low placenta weight in their first pregnancy had an increased risk of developing preeclampsia in their next pregnancy.

The size of the placenta can tell us something about the mother's future pregnancies.

“The risk increased by 30 per cent compared to women who had average placental weight in their first pregnancy,” says Larsen.

Recording the weight of the placenta in the first pregnancy can thus help to identify women at increased risk of developing preeclampsia in future pregnancies.

Two types of preeclampsia?

However, high placental weight also increased the risk of preeclampsia in subsequent pregnancies among women who had not had the condition before.

Previous research suggests that two variants of preeclampsia exist. One variant starts early in pregnancy, and another develops only towards the end of pregnancy, at term, Larsen explains.

“Our different findings in relation to placental weight support the theory that they are different diseases,” says Larsen.

Previous research also suggests that preeclampsia that begins early in pregnancy and the variant that develops only toward the end of pregnancy may have different causes.

Both conditions create the same symptoms but can be two separate diseases with different causes.

Not measured during pregnancy

This research is based on taking placental measurements at birth. Finding the risk of dangerous health conditions while the woman is pregnant is not possible with this method.

“So far, no placental measurements have been introduced as part of prenatal care,” says Larsen.

However, other research is going on that has measured the size of the placenta using ultrasound and MRI. The results of this research are not yet available.

Mothers who are planning to have more children also cannot access the weight of the placenta from their last birth.

“No, unfortunately you can only get information on the current birth weight right now. But I think this information is just in its starting phase and hasn’t had any need for follow-up yet,” Larsen says.

She hopes that will change as the knowledge about placenta growth during pregnancy begins to spread from the ongoing studies.

Over 700 000 women participated

The study on preeclampsia included 186 000 births.

Medical birth records were used to determine mothers' smoking habits and their newborns’ birth weights. Information from all 700 000 women's births forms the basis of this study.

In the study where they found the link between the size of the placenta and the mother's blood percentage, researchers used information on 57 000 births at Ahus in the period 1998 to 2013 from PARTUS, a medical record system in the maternity wards.

References:

J. Dypvik J, S. Larsen et al: «Placental weight in the first pregnancy and risk for preeclampsia in the second pregnancy: A population-based study of 186 859 women». Summary. European Journal Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, May 17, 2018.

S. Larsen et al:« Placental weight and birthweight: the relationships with number of daily cigarettes and smoking cessation in pregnancy. A population study». Summary. International Journal of Epidemiology, June 26, 2018.

S. Larsen et al: «Placental weight in pregnancies with high or low haemoglobin concentrations». Summary. European Journal Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. August 31, 2016.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no