He knows where the voices in your head are from — and maybe he can stop them

Kenneth Hugdahl has found out where the voices in your head come from. Now he hopes that it will be possible to turn off the switch.

People who suffer from schizophrenia live a life that is dominated by voices in their head. Sometimes the voices stop. Kenneth Hugdahl has found out what happens when the voices begin to speak, and what happens when they suddenly fall silent. The findings may be the first step towards treatment for people who hear voices.

Hugdahl is a professor of biological psychology at the University of Bergen and a researcher at Haukeland University Hospital. In fact, he should have retired four years ago. Instead, he continues to study the voices that no one else hears except for the person who hears them inside their head.

Aural hallucinations

“What we are working with is essentially aural hallucinations, or hearing voices. I am particularly concerned with hearing voices as a serious symptom of one of the most serious mental disorders we know, schizophrenia,” he explains.

Anyone who has these kind of auditory hallucinations experiences them as if someone is actually talking. “That voice is clear, just like you hear my voice now,” Hugdahl says on the phone to sciencenorway.no. The sound waves from his voice hit the journalist's eardrums, electrochemical signals cause nerve cells in the brain to react, and the brain perceives the content in the form of language.

Measures blood flow in the brain

The strange thing, Hugdahl thinks, is what makes the brain create a completely similar experience even when there are no sound waves reaching the ears. It’s the brain that provides this misinformation — the information doesn’t come from outside.

Hugdahl and his colleagues have used fMRI to find out where in the brain the nerve cells react.

FMRI is an MRI machine just like the one that uses magnetic fields to take images and determine where in your knee it hurts, or if you have a tumour in your brain. But the researchers set up the MRI machine a little differently so that it measures the blood flow in the brain.

The blood carries oxygen to the nerve cells. There it is used as fuel in a complex biochemical process. The images from the fMRI show where nerve cells get extra oxygen.

Hugdahl compares it to a car. When the car is going uphill, you have to step on the accelerator pedal because the engine needs more fuel to move the car up the hill. Similarly, brain cells need more oxygen when they have more work to do.

Same area as when someone is talking

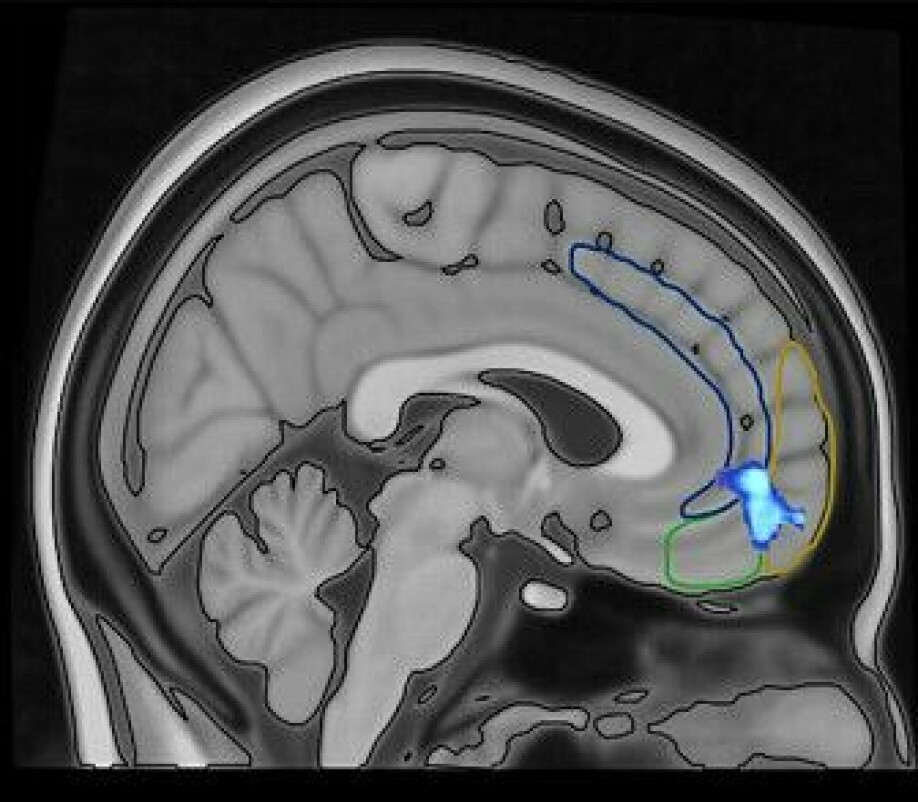

“I put patients who hallucinate into the machine. What we found was an area in the posterior, upper temporal lobe on the left side — slightly above the left ear, but inside the brain. That area is suddenly much more active when you hallucinate,” he says.

This particular area is just as active at another time, too — when someone talks to you. Hugdahl refers to it as the area where you experience speech or the area of language perception. In other words, this area, which is active when you hear an actual voice, is just as active when the voice you think you hear only exists inside your own head. This may explain why the voices are perceived as completely real, Hugdahl said.

Comes and goes

These findings were the result of the first grant he received from the EU. Then it struck him: All the literature and all the research focus on what triggers the voices; what sets them off. But almost no one experiences the voices 24 hours a day, day in and day out. They come and go. Some hear them often, some almost all the time, but never 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“What is it that makes the brain suddenly stop the voices?” Hugdahl wondered. He was grated another NOK 25 million to find the answer.

He fired up the MRI machine again, this time equipped with two buttons that the patients could use. They were supposed to press one when they heard the voice beginning to speak to them. They were to press the other when the voice disappeared.

Here’s where the voices begin

The researchers noted the exact time each button was pressed. They then synchronized these data with the recordings from the brain. Once again, they found a very concrete and clear connection.

“We found another area in front of the brain — a little above and inside the pit between your eyes. We know that this is the part of the brain that has the control functions that that control many of our decisions,” says Hugdahl.

Three to five seconds before the patient heard the voice, this area of the brain was suddenly very active. Activity in the same area dropped again three to five seconds before the voice disappeared. The brain responds a little faster than the consciousness.

Found the 'conductor'

“Now we had found a kind of control area. It works almost like a conductor in the orchestra. The hypothesis is that this conductor controls what happens in the temporal lobe in the language area. The conductor raises the baton and tells the orchestra to ‘play’ or ‘stay quiet’,” said Hugdahl.

This particular part of the research is so new that it has not been repeated yet. To be completely sure, other researchers have to check Hugdahl’s results and see if they can replicate them.

But Kenneth Hugdahl and his group did not stop there. They went on to step three.

“If we run the MRI machine in a special way, we can also measure the concentration of selected signalling substances. There are certain chemical substances in certain areas of the brain, such as dopamine and serotonin,” he says.

The brain’s gas and brake

Hugdahl focused on two other neurotransmitters: Glutamate and GABA. When there is glutamate between two nerve cells, the nerve fibres connect. The more glutamate, the more active the nerve cells. He compares glutamate to the accelerator pedal on the car.

GABA, on the other hand, is the brake for brain cells. When there is a lot of GABA between the nerve cells, it slows down activity.

“We found elevated levels of glutamate in the temporal lobe, and we found levels of glutamate in the parietal lobes that were too low. There is an imbalance at the neurochemical level. We believe the explanation is that the imbalance comes and goes, which in turn explains why the voices come and go,” says Hugdahl.

Dreaming of treatment

With all these findings in place, the dream is that it will be possible to treat voices in the head.

“Schizophrenia is a very complicated mental illness. There are up to 25 different symptoms. Medicines try to address the disease in its entirety, and medication does not always work. But almost all doctors will probably say that hearing voices is one of the most serious symptoms. It takes control of the patients and then completely dominates them,” he says.

At best, it may mean that other symptoms can be dealt with if the voices in the head remain quiet.

Everyone hears voices

Hearing voices is also a characteristic of a number of other psychiatric and neurological disorders, such as bipolar disorder, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and epilepsy. Cannabis can also cause people to hear voices in their head.

Five to ten per cent of the population think they hear voices, but are not bothered by them. The content is more positive, and they feel like they have control over the voices. We all hear voices from time to time when we wake up. Then we wonder: ‘Was it a dream or was it reality?’. When something interesting happens in the environment, we just move shift our attention outwards. Patients with schizophrenia cannot do that,” Hugdahl said.

Doctoral degree with voices

Solveig H.H. Kjus hears voices herself. She has a doctorate in space physics, is a co-researcher at the National Competence Centre for Mental Health Work and has a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

“I don’t really experience them as voices like I hear with my ears, but more like messages I get inside my head. I don’t feel like my ear is involved,” she explained in a podcast from the magazine Psykisk Helse (Mental Health) in 2019.

Kjus is not sure what she thinks about the possibility of 'turning off' the voices.

“Based on my experience, it might have been an advantage, but I have also had the advantage of having the voices. I have managed to complete my doctorate because of them — they gave me a lot of drive and pushed me. But the people who have been treating me say that I would have had the drive to do it on my own,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no