Prisoner of war Roar Antonsen smuggled letters and shoes out of Grini prison camp during World War II

Two pairs of children's shoes tell the incredible story of one man's dream of living in freedom, with his wife and the twins he has never met, and about resistance work at Grini, Norway's largest prison camp during World War II.

Two pairs of children's shoes are on display at the Grini Museum. They belonged to the twin daughters of Roar Antonsen. He was imprisoned at Grini prison camp for two years, before being sent to a concentration camp in Poland.

Lead curator Camilla Maartmann chose these shoes when we asked her to select an object from the exhibition.

“The shoes tell a gripping story about one of the prisoners, about their life in the camp and their resistance to oppressive forces,” Maartmann says.

Arrested just before the wedding

Around 40,000 women and men were arrested in Norway during the five years of German occupation. Many of them ended up in prison camps, without a sentencing, indefinitely.

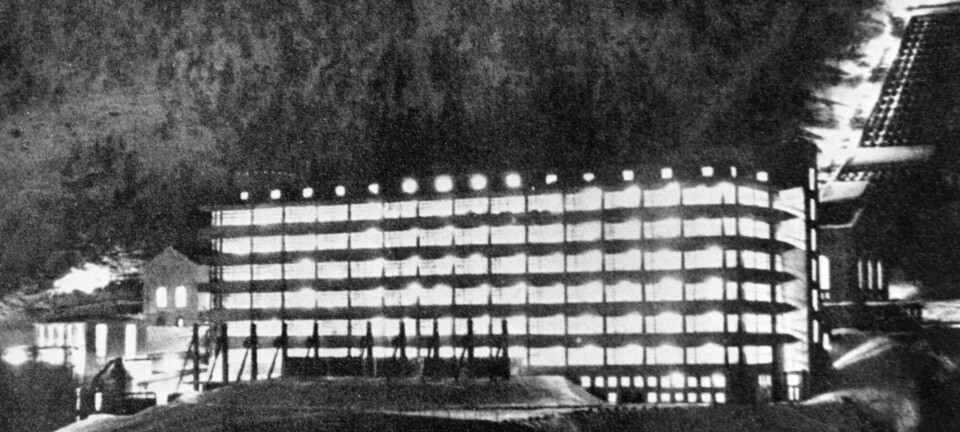

Grini prison camp was the largest in Norway. The first prisoners arrived here in June 1941.

At that point, Solveig Nilsen and Roar Antonsen from Oslo had just met at a Midsummer party.

“They fall in love and became a couple,” Maartmann says.

The following year, Solveig and Roar plan their wedding. Guests are invited and the church is booked. Only the two of them know that Solveig is pregnant.

“But then Roar is arrested before they have time to get married. He is 26 years old,” says Maartmann.

Distributed illegal newspapers

The Germans shut down or censored Norwegian newspapers. So, illegal newspapers became an important part of the resistance against the occupiers. The focus was to keep peoples’ spirits up, while also spreading information about what was really happening in Norway and the rest of the world.

Roar Antonsen was involved in printing and distributing illegal newspapers. He also had an illegal radio hidden in his outhouse. This made it possible to hear news from England.

The Gestapo, the German police in Norway, picked Roar up from his parents’ home and brought him to the police station in Møllergata 19. There, prisoners were interrogated and often tortured.

After six months in solitary confinement, Roar is sent to Grini. He has not received a sentence. He does not know how long he will serve.

Two girls are born

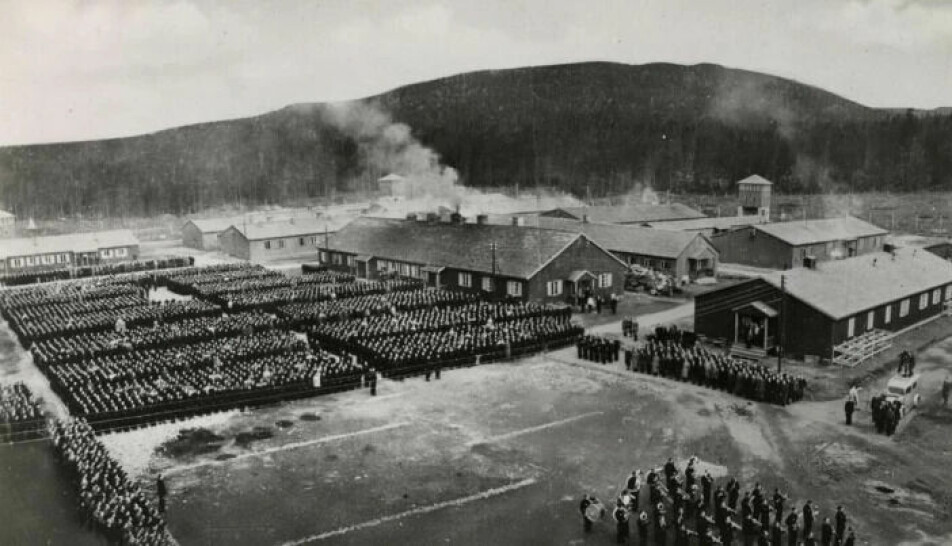

Every morning, the prisoners must line up at the Appellplatz for roll call. There they receive orders and messages. One morning in September, it is announced that prisoner Antonsen has become the father of two girls.

But prison life continues just as before.

“For Solveig, life as an unmarried mother was not easy. It was, for example, very difficult to get the two girls Tone and Sissel baptised, because the priest did not want anything to do with what they called illegitimate children,” says Maartmann.

Solveig wants to get married but Roar is behind barbed wire fences in Grini. They find a solution. A friend of Roar takes his place in a proxy wedding. And so they get married.

“The other prisoners arrange an illegal party for the man who is not allowed to be present at his own wedding,” Maartmann says.

They celebrated 'The twin dad', which had become his nickname in the camp.

Resistance within

All the prisoners at Grini are given jobs in the camp. Roar gets a job in the bread shop.

Although the camp tried to be as self-sufficient as possible, there were too many prisoners for them to bake all the bread themselves, according to Maartmann.

Nearly 20,000 prisoners of war entered Grini during the war. The camp was constantly expanded, and they built a total of 40 barracks around the prison building.

This is how Roar ends up working on one of the most important smuggling routes in and out of the camp. The bread shop is the post office for secret letters and messages.

“The prisoners resisted. They formed a secret organisation that smuggled messages in and out. This is how they could relay who had been taken to Grini so that others could escape. Or send messages to the family of those who were executed,” says Maartmann.

Private letters were also smuggled in and out of the camp. In these letters, prisoners would let others know they were alive and still in Norway.

Letters inside bread and boxes

Prisoners at Grini created holes in the corners of containers used to transport bread. They hid messages there. The bakery Baker Hansen delivered both the bread and letters.

“Sometimes letters and messages were stuffed into hollowed-out bread,” Maartmann says.

Roar Antonsen is given responsibility for the bread coming into Grini. He himself writes letters to Solveig, resulting in more than 40 letters from Grini.

Solveig kept them all. Camilla Maartmann has read them.

A gift for his daughters

“In one of Roar's letters to Solveig, it says that he has had shoes made for their twins. A prisoner who worked as a shoemaker helped him. Roar managed to get the shoes smuggled out. They were the twins' first shoes,” Maartmann says.

In his first few letters, Roar writes that he feels confident that he will not be sent to Germany. That was a Grini prisoner’s worst fear.

After two years in the prison camp, some anxiety emerges in the letters.

“Now he is worried that it will soon be his turn to be sent away. But he comforts his wife. He reckons he will be sent to the same place as all the others,” says Maartmann.

Most of the male prisoners at Grini have been sent to the Sachsenhausen camp in Germany. Naturally, Roar believes that he will also be sent there.

In August 1944, his name is called out.

Sent to a concentration camp

Now it’s his turn to be transported to Germany, like so many others before him. But Roar is not sent to Sachsenhausen like the others. Together with 44 men and 18 women from Grini, he ends up in Stutthof, a concentration camp near Gdansk in Poland.

“Roar ends up in the worst part of the camp, but he was lucky. He got to work in an office,” says Maartmann.

There he again gets the chance to send letters home to let them know he is still alive.

In January 1945, it is clear to the Germans that they will lose the war. Russian soldiers are approaching. So the Nazis move their prisoners out of the camp, away from the Russians. It's freezing. Their clothes freeze to ice. They are starving. Those who cannot keep up the pace are shot.

During these brutal marches, many die of injury, disease, starvation, and hypothermia.

Marching for two months

“Roar has also been chased out on a death march. He has managed to smuggle a picture of Solveig and the twins with him,” says Maartmann.

Roar and the other prisoners march for two months. Those who perish are left in ditches by the road. Roar manages to survive.

Soon, they are liberated by Russian soldiers. But Roar is in a place where no white buses will come to pick him up and bring him home.

“The road home is unbelievably long. It's chaos. The prisoners are gathered in internment camps. Roar escapes, gets a little further, but ends up in a new camp,” says Maartmann.

Coming home

And then, finally. In June of 1945, Roar manages to get a plane from Hamburg to Oslo.

Solveig has heard rumors that Stutthof prisoners will come home, but she does not dare to hope that it will finally happen.

Nevertheless, she puts the twin girls in nice dresses and asks them to pick flowers for their father. Finally, he stands at the gate, and he gets to hold his girls in his arms for the first time.

Love, longing and resistance

“For me, these shoes represent so much. First, it's a gripping love story and a father's longing for children he's never seen. But it's also about resistance, about the prisoners who refused to submit,” Maartmann says. “And of course - and this is the most important - the will to live and survive as a prisoner.”

The shoes are featured in an exhibition inspired by the Austrian psychiatrist Victor Frankl, according to Maartmann.

Frankl was a Jew and survived the Holocaust but lost his entire family. During his time in a concentration camp, he developed a life theory: That life has meaning no matter how hopeless it may seem.

Frankl thought of his wife. She was killed in one of the camps, but he did not know that at the time. He also thought about completing his dissertation, which he had started before the war.

The life that followed

“For Roar, it was meaningful to work in the resistance group and smuggle notes, but perhaps most important was the thought of Solveig and the girls, and the life he would build with them upon his return,” Maartmann says.

This also permeates their letters. Roar writes that he will hold Solveig in his arms and that he will go for walks with the girls. Thinking about the life he had waiting for him was a survival tool.

Many of those who survived the German concentration camps did not fare so well. They struggled with anxiety, depression and survivor’s guilt. How could they have survived when so many had died?

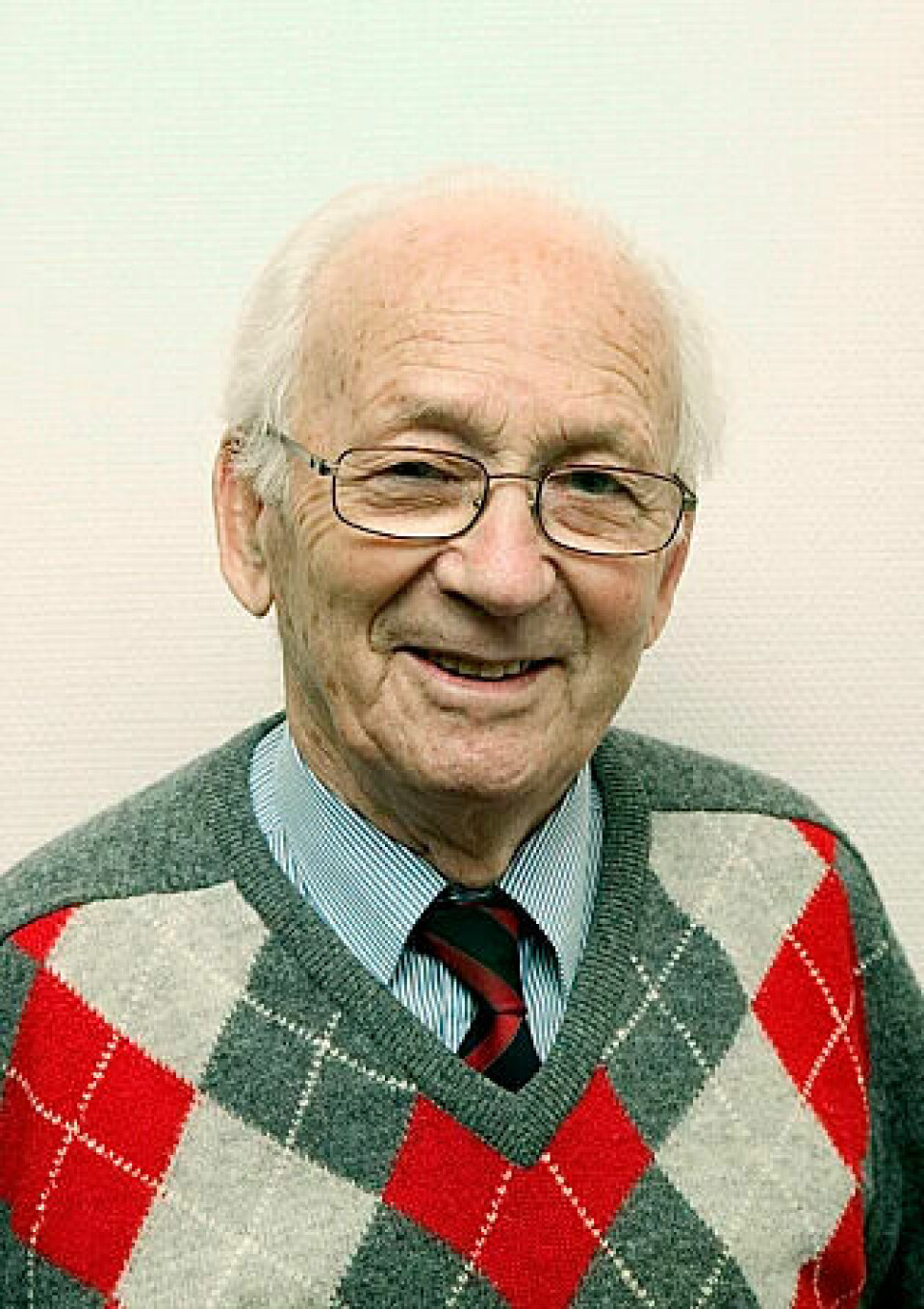

“Roar fared well after his homecoming. He was a skilled organisational man and later became president of the Norwegian Ski Association,” says Maartmann.

Roar and Solveig had two more daughters, and made it to their 70th wedding anniversary.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Grini Museum: About Grini prison camp (link in Norwegian)

Thomas Wyller: W/25X. The resistance struggle on Grini. Aschehoug 2009