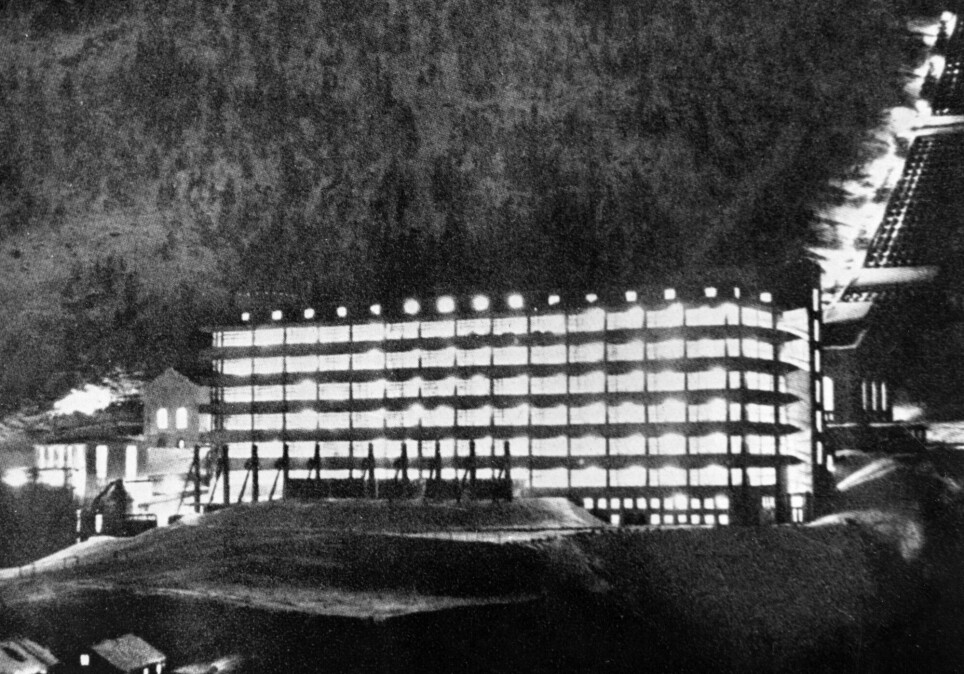

One of the most famous acts of sabotage during WWII happened in the basement of this building. Now it's open to the public

On a mission to prevent Hitler from developing a nuclear bomb, a group of brave soldiers made their way into the basement where heavy water was being produced. That very basement was rediscovered a few years ago.

In 1943, a basement in the hydrogen factory Vemork, Rjukan was the location of one of the most famous acts of sabotage in world history.

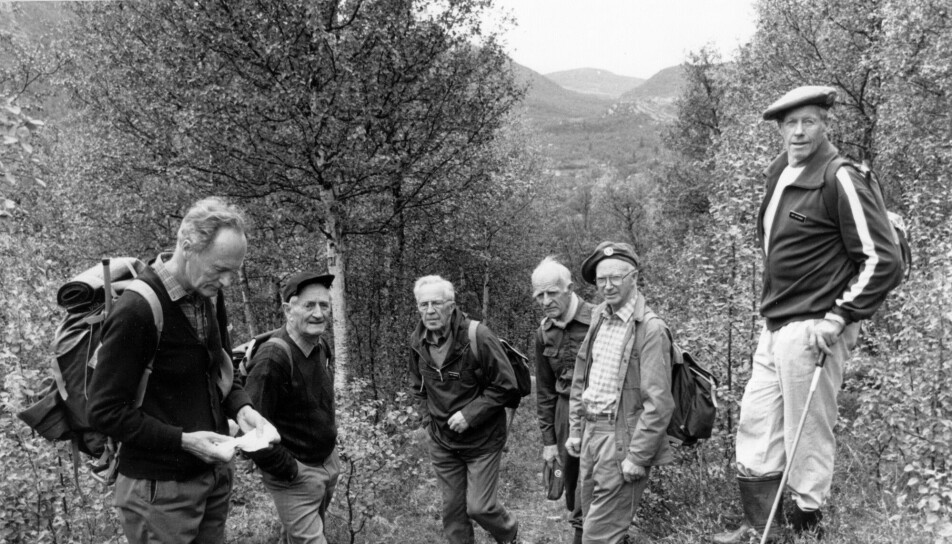

Having climbed down a steep gorge with a river flowing through it – in February, in the middle of winter – a group of Norwegian saboteurs made it unseen up to the factory.

Five men kept a lookout for German guards, while four other soldiers made their way into the basement where the heavy water was being produced. 4.5 kilos of explosives were placed, the fuses were cut to a mere 30 seconds to be sure they would blow up, and all four men still made it out before the bang.

Operation Gunnerside, as it was called, was exceptionally successful - and no lives were lost.

An industrial cathedral

Heavy water, an easily available biproduct of hydrogen production that was taking place at Vemork, was sought after for nuclear research - and possibly for the production of an atomic bomb. During World War II, the Norwegian resistance movement did everything they could to prevent the Germans from getting hold of the heavy water.

Operation Gunnerside was “one of the most daring and important undercover operations of World War II”, according to an article by the BBC. Movies and TV series have been made about the famous act of sabotage.

In 1977, however, the building was blown up and leveled because it was no longer in use.

40 years later, the basement was found intact by, amongst others, archaeologist Sindre Arnkværn.

“It was like entering an industrial cathedral of sorts,” Arnkværn says.

Hoping to find a floor

According to the archaeologist, who works for the county municipality of Vestfold and Telemark, there were no high hopes when the excavation started in 2017.

“We were trying to find a floor, that was our goal. We thought the rest of the structure had been blown away,” Arnkværn says.

Then one day the archaeologists found a window and realized that they were staring straight into an intact basement.

“It was a nice day at work, to put it mildly,” Arnkværn says.

“Being an archaeologist and discovering something that you can actually enter is stuff you hear about from Egypt and other such places. So that is spectacular in itself,” he says.

“The history that is connected to this basement makes it a dream scenario for an archaeologist.”

It was one of the sabotoeurs, Joachim Rønneberg, who first suggested that the historical basement be restored for future generations to enjoy, according to an article from the Norwegian National Broadcaster (link in Norwegian). Perhaps helped by the attention gained through the NRK TV show The Heavy Water War (called The Saboteurs in the UK) from 2015, money was put on the table to start digging for remains of the basement.

On June 18 this year, the doors to the intact ‘industrial cathedral’ were opened to the public.

A gold mine for hydropower

“The saboteurs came down from the valley up there,” says Gunhild Lurås and points up the steep mountainsides of the Vestfjord valley. She is the exhibition manager at the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum.

Rjukan is located in Vestfjorddalen in Tinn municipality and was a small settlement consisting of only a few farms up until the beginning of the 20th century.

The western valley in Telemark was an unopened gold mine for hydropower, and Norsk Hydro saw the potential. One May day in 1911, Vemork power station was put into operation as the world's largest power plant.

A hydrogen factory with a mythical cellar

Hydro started the production of hydrogen at Vermork in 1929. The hydrogen factory required a lot of electricity and was built right next to the hydropower plant. And in the basement the production of the famous by-product: heavy water.

“This was not a heavy water factory, but a hydrogen factory,” exhibition manager Lurås states.

She and her colleagues at the museum say that many people wonder why heavy water was produced in Rjukan.

The short answer is: because there was a hydrogen factory there, and it was technically possible.

“This heavy water cellar has almost become mythical,” says Anna Hereid, director of the Norwegian Industrial Workers Museum. “First through the industrial adventure, and later as the scene of one of the most famous sabotage operations the world knows.”

The industrial heritage of Rjukan, and thus Vemork, was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2015.

“Some were willing to give their lives”

“I am simply moved,” Tove Kayser says. She is the daughter of Fredrik Kayser, one of the heavy water saboteurs - and the last man out of the basement before the explosion.

Kayser is grateful for the drive and effort behind the restored basement. She believes it will be an important reminder of why we have peace and freedom of speech: some were willing to give their lives.

“I am one hundred and ten per cent sure that this will lead to many good experiences for children and young people,” Kayser says.

Her father, however, told her little about the events of that night in February in 1943.

At a press screening for the new museum, Kayser was asked how her father experienced his story being passed on.

“He did not talk much about it until he realised that people had started to forget what they fought for during the war. At that point he felt he had to do something, and started visiting schools and telling students his story,” she says.

“This was an operation that went perfectly well, so why should he talk about it?” she quotes her father.

Not a small bang at all

It has been said that the explosion itself was just a small bang.

“But he could tell us that it was not a small bang at all. He was the last one out, and he heard a terrible bang - he even turned around and saw the pillar of fire,” Kayser says.

However, there were many other sounds emitted from the huge power plant at the same time.

“That was probably why the Germans did not notice the bang,” she says.

All of the heavy water the Germans had produced during the occupation, as well as critical equipment, was destroyed in the raid. The damage wasn't permanent, but it halted the production for several months.

Although the Germans dispatched 3000 soldiers to search the area, all the saboteurs got away.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik.

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no