People in the 17th century feared war, death and the end of the world as we know it, a songbook reveals

Peder Rafn's songbook gives us insights into what people were concerned with in the past.

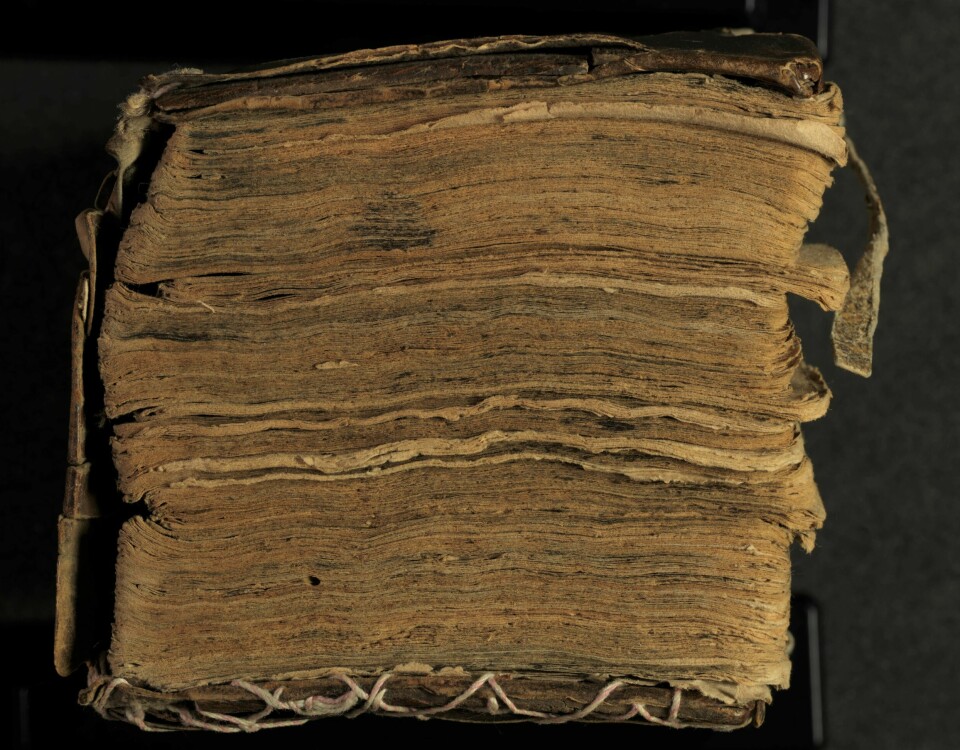

The National Library of Norway (NB) recently launched a new, modern version of Peder Rafn's songbook. This is the Nordic region's largest single collection of songs from the 16th and 17th centuries, according to Siv Frøydis Berg and Trond Haugen, both of whom work at the library.

“The songs are about everything from the big connections to people's personal experiences. They deal with life, death, life after death, but also war, politics, love, grief and loss,” says Berg.

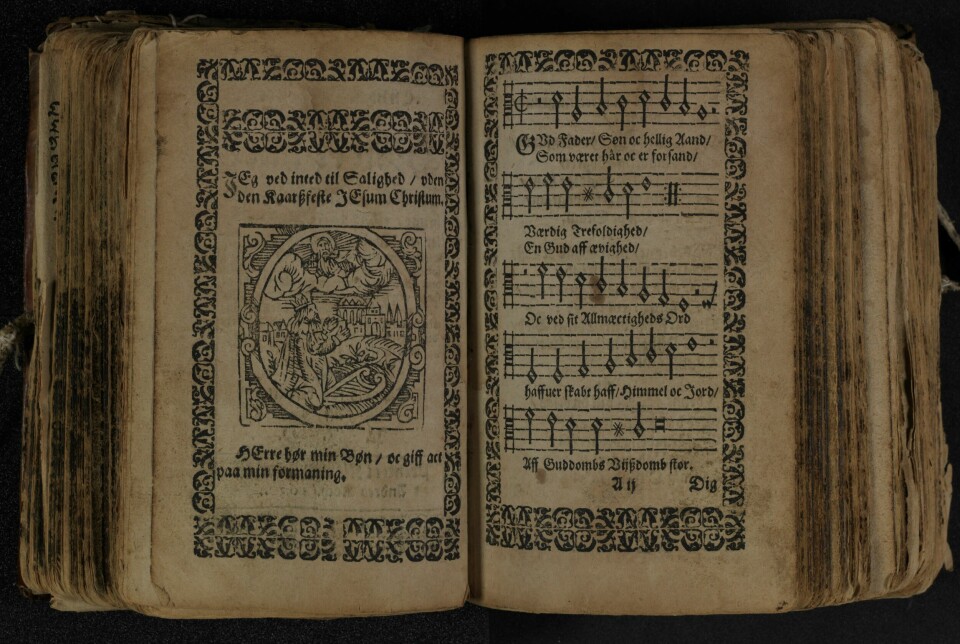

In the 17th century, songs were printed and shared among people. These printed song sheets were simple affairs. They were small, folded pieces of paper that were sold in the marketplaces.

“Books were valuable at this time. They were inherited and well cared for. But the small song sheets have largely disappeared. They were worn out and thrown away,” Berg, who is a historian of ideas and a research librarian at NB, said.

Some have nevertheless been preserved.

The hippest songs of the time

The craftsman Pouell Maurysen collected 106 such song sheets in a large book. He gave this songbook to his employer, Peder Rafn.

The first song in the collection may originate from the wedding between Rafn and Karen Hansdatter twenty years earlier, the researchers believe.

“Peder Rafn gets a gift that is a last cry from Europe. They were the hippest songs from the world out there,” says Berg.

Altogether there are 170 songs in the book, distributed over 1,000 small pages. Some are translated from other languages, others are new texts set to well-known melodies.

Peder Rafn received the book in 1641 in Copenhagen. The researchers know this because it is written on the inside of the book cover.

Rafn had been a lawyer in the Norwegian cities of Bergen and Stavanger. It is likely that he took the fine gift with him to Stavanger, located in southwestern Norway, when he returned there.

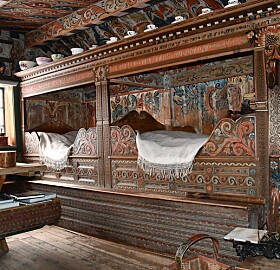

Then the book disappears out of sight of historians, before it turns up on a farm in Lærdal in Western Norway.

“There is a gap of 100 years where we are unsure where the songbook has been. But after 1745 it was on the Hynjo farm in Lærdal, until it ended up in the Heiberg Collection (a cultural heritage museum) in 1934,” says Trond Haugen, a research librarian at NB.

Threatened by the Pope, the monks and the Turks

The oldest printed song sheet was created 50 years after the Reformation, at the same time that Norway became a dependency of Denmark.

Both the change in religion and Norway's loss of status as a separate kingdom were established by military force. All resistance was dealt with harshly.

Nevertheless, there is little opposition to these societal changes in the songs.

In contrast, the Catholics, the Pope and the monks are described as dangerous enemies. The Turks are also a strong threat, according to the lyrics.

“The Ottoman Empire was a strong military power. The songs contain a lot of propaganda against enemies that posed a threat,” says Haugen.

The people of this time were preoccupied with the end of the world. They interpreted signs in nature and were worried about how society was changing.

Warns against foreign fashion

“The idea that the end of days has come is a central theme in many of the songs, says Berg.

This downfall is humankind's own fault. They have sinned.

Under Catholicism, people could influence whether they ended up in heaven or hell. They would end up in purgatory after death, and there they could make up for their sins. This possibility disappeared with Protestantism.

“After the Reformation, it is faith alone that decides. Whether you get to Paradise is about you, your faith, deeds and the life you have lived on Earth. It becomes more important to have a good lifestyle and live properly. The Christian virtues are more important,” Berg said.

Several of the songs are about doomsday and how to end up in the right place afterwards. They come down hard on trickery in business dealings and high interest rates.

The signs of the Earth's doom were found in nature and in the sky, but also in women.

“They are also warned against being vain and following foreign fashion,” says Haugen.

Protestant Massacre

War, politics and religion are the themes of a number of the songs.

Europe is at war beginning in 1618, in what was later called the Thirty Years' War. One of the reasons was the conflict between Protestants and Catholics, according to Wikipedia.

The Protestant city of Magdeburg in Germany was besieged by Catholic forces. The residents eventually surrendered, but too late. The message never reached the Catholic commander. On 20 May 1631, 40,000 soldiers stormed the city.

They set fire to houses, and the fire spread quickly. The soldiers had not been paid, and they demanded valuables. When the residents had nothing more to give them, the violence, torture, rapes and murders began.

There were 25,000 people living in Magdeburg. Only 5,000 survived the storming.

Propaganda for war

One of the songs in Peder Rafn's song book is about the massacre in Magdeburg. The researchers call it a news song — this is how people heard about the war's losses and victories.

“Think how quickly a song can spread. It just requires someone to remember the text,” says Berg.

The Magdeburg song dramatizes the massacre. It describes disbelief and shock at the atrocities.

“This is also propaganda. An argument for continued war,” Berg said.

Another song boasts of a naval battle at Hamburg, Germany. The Protestants won the battle and are described as good, brave soldiers.

Other songs argue that Denmark-Norway should join the war. King Christian IV wanted it, while the State Council said no. One of the songs supports the king.

“You get a sense of the fear of war. The songs are so long with many verses. You can feel the fear rising, the enemy moving closer and closer. Messages come from here and there. They ask: Where is the king, where is God?” says Berg.

When Oslo burned

Oslo burned in 1624. The wooden houses were gobbled up by flames. Almost all residential buildings and food stores burned down. After three days, the city was in ruins, according to the Oslo city dictionary.

Two years later, the merchant Hans Nilssøn Gris wrote a song about the fire.

According to the researchers, this is the first fictional description of the Oslo fire.

“The song is about how the catastrophe struck Oslo residents because they had not followed God's word,” Haugen said.

King Christian decides that the city, which will now be named Kristiania, will be built in brick, to avoid another fire disaster. This is later to become Kvadraturen, a popular shopping district in central Oslo which still has buildings from the 1640s.

The song says goodbye to old Oslo, called Ansla, and welcomes new Kristiania.

Adieu you good

Ansla/

I bid you good

night;

Hello

Christiania/

When I take

hold of you.

Unhappy love

A number of the songs are about love. Some of them gently hint at eroticism: "I want to walk in your rose garden."

Grief in love is the subject of another song. A young woman has been abandoned.

“She is very sad. She would rather die than be so unhappy,” Berg said.

The woman in the song would be happy if she had never met her beloved. She gave her heart to him, but he rewarded her with adultery.

Oh, how happy I

would have been/

If I had never

seen you/

I had my heart turned toward you/

But you repaid

me with unfaithfulness/

Many clues to the past

Siv Berg and Trond Haugen now hope that other researchers will take up Peder Rafn's songbook. They believe the songs are well suited for further research.

“There are many clues to follow. They can look at the lyrics, the music or the politics. The songs are a source of information about mobility, and the history of books and printing. They are a rich and unique source material for a common European culture of which Norway was a part,” Berg said.

The songbook gives us a picture of what the people of that time were concerned with.

“You get a sense of getting closer to the people of the 17th century,” Haugen said.

But what about using the songs as they are intended? To sing?

That’s entirely possible, but at the moment it requires some work.

“We refer people to the melodies and the sources where it is possible to find sheet music. But people have to find the old notebooks themselves,” Haugen said.

“But I have a dream of publishing Peder Rafn's musical notebook,” he says.

———

Translated by: Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no