The culture of sleeping: Some slept in rose-painted beds, others barely had time to sleep

In his new book, cultural historian Bjørn Sverre Hol Haugen takes us back to a time when decorative beds were a status symbol, and having to share a bed with random relatives was quite normal.

For some of us, sleep is a necessity that is hard to find time for in a stressful everyday life. Some even stay up late even though they should sleep, just to steal a little time for themselves.

Sleep has also been a rare commodity during previous centuries, and precisely this often contributed to creating a divide between rich and poor, women and men, according to researcher and author Bjørn Sverre Hol Haugen.

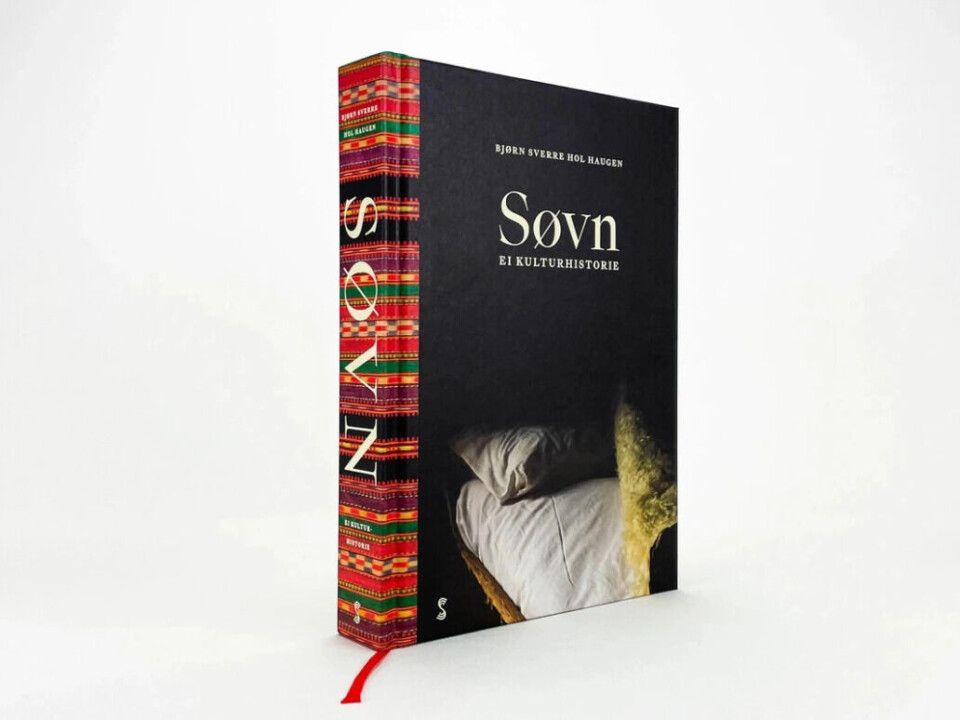

Haugen is the head conservator at Norsk Folkemuseum (which roughly translates to the Norwegian folk history museum) and an associate professor in cultural history and museology at the University of Oslo. He recently published the book Søvn – ei kulturhistorie; Sleep – a cultural history, where he delves into the questions of where and how Norwegians have slept through the ages.

Haugen has seen countless old beds during his many years as a conservator and museum director, but little has been written about them. He had wanted to investigate the topic further, and the Covid pandemic finally gave him the time he needed to complete his book project.

Haugen is most interested in the 18th and 19th centuries. In particular, he explores how people arranged their material needs for sleeping, such as their beds, bedding and the houses they slept in.

Always working

Haugen finds Christian Krohg's painting 'Sleeping mother with baby' from 1883 an apt depiction of the reality of that age. The woman in the picture has her knitting in hand.

“Morality dictated that you should never be without work,” Haugen says.

Nor was there room for much else than work and rest. Haugen writes that working people probably slept between five and seven hours until the second half of the 19th century. Sleep might have increased somewhat after that, as farmers acquired more farming aids.

A 16-hour workday from 4 o'clock in the morning (or at night...) to 8 o'clock was probably the norm at this time.

But workers might have been able to compensate a little between their stints of labour. Haugen explains that the work day was carefully organised. There were fixed meals and time for rest after the meals. The afternoon rest could be long – one and a half to two hours. Many people used the time to get some much-needed sleep.

Well, men did, anyway. Women often did not have the same division of their working day as men. When the men finished eating, women had to do the dishes.

If women worked in the men's arena and engaged in outdoor work, they had the same rest periods as men. Haugen also writes that some women had short breaks throughout the day as they found the time and need for it. Women's time was less regulated. Morality dictated that they should preferably be doing something all the time. Knitting projects came in handy then.

Inspiration from Versailles

You have no doubt heard of four-poster beds, which is actually a common term for beds with superstructures.

“The model for these ostentatious beds can be found in Europe. We can travel straight to the palace in Versailles,” says Haugen and shows the picture of Marie Antoinette's throne bed.

“Although some written sources indicate that Norwegians also had throne beds, we have to assume that they were adorned with a little less gold and silk,” he comments.

There is also no doubt that the vast majority of beds were considerably simpler.

In any case, it was important for the well-to-do farmer to show his wealth, writes Haugen.

Beds as status symbols and life symbols

Farmers could show their power and wealth in various ways, including with richly decorated beds. Many of them were built in or covered, and they could be richly decorated.

Danish ethnologist Mikkel Venborg Pedersen also writes that beds were status symbols in an article published in the scientific journal Ethnologia Europaea in 2005.

Venborg wrote the book I søvnens favn (In the embrace of sleep) about the cultural history of sleep in Denmark. It was released in 2009.

He compares the status of beds in earlier times with the status of automobiles today. We show status by buying a big and expensive car and parking it in plain sight in the driveway.

But there is something about the bed that makes it important in several ways. Pedersen says that he has made many beds at the Open Air Museum in Denmark – some very well adorned, others more meagerly so.

“More than any other piece of furniture, the bed is a symbol of life,” Pedersen writes.

The bed is the place for sleep, lovemaking, resting during illness and often also where you take your last breath.

Pull-out beds

Not everyone had flashy four-poster beds. But pull-out beds could be practical and have the option of being extended – some lengthwise, others widthwise.

This way, they could be pushed together and take up less floor space during the day when no one was spending time in them, and they could accommodate a lot of people for sleeping.

One of the best-known combination pieces of furniture is the slagbenk, a convertible bench. You can still buy one at IKEA today, but they were already known in Denmark in the 16th century, according to Store Norske Leksikon, the Norwegian online encyclopaedia. It served as a place to sit during the day and a place to sleep at night for servants or guests, for example.

The slagbenk was an early version of the sofa bed – which, Haugen tells us, is hardly a new phenomenon. It came into use in the latter half of the 19th century.

Cramped quarters

Today, most people are able to sleep in their own bed, except for lovers and married couples, who sleep together. And they generally prefer to sleep together each in their own half of a double bed.

In the past, several people quite commonly slept together in much narrower beds. And the distribution was more random. You might have to sleep with grandma or another family member. That's just how it was.

Two or three people in each narrow bed were the norm. Most often they were of the same sex if both were adults, but servant girls and boys on the farms might also have to sleep in the same bed.

Intimate bed conditions could be expected when people slept away from home. Suddenly you would be lying next to a stranger. One example is when the National Assembly met at Eidsvoll in 1814. The accommodations varied considerably, even for these important men - 112 elected representatives - who on May 17th that year adopted the Norwegian constitution and formalised the dissolution of the union with Denmark.

The representatives had to sleep on farms around the village, says Haugen. While some were happy and had their own made-up bed, others had a tougher time sleeping on far away farms. Damp sheets, poorly tended homes and limited space were some of the complaints.

Bed rules at Eidsvoll

Provost Frederik Schmidt and bailiff Johan Collett had to share a short bed. They chose to lie head to feet, that is, in opposite directions. Haugen has included this excerpt from Schmidt's diary:

‘C. and I became antipodes and since our beds were barely 2 ells long, we had to craft a Constitution about our bed rules, in which it was adopted and made law that each party's own 2 legs should follow the agreed to diagonals, however with the proviso not to kick the opposite [person’s] nose, which stood an insignificant distance from the tip of the big toe.’

So they had to make bed rules. The legs were not to cross the boundaries they set, and it was forbidden to kick the other's nose – which, by the way, was an ‘insignificant distance’ from the tip of the toe.

Loggers, on the other hand, usually slept in very cramped small bunks. You can read more about them in an article from earlier this year.

Dark sleep tips

In contrast to the familiar everyday events, Haugen also writes about so-called sleep magic in the book.

The ‘black books’ of folk magic (also called Cyprianus) offered tips on how to get others to sleep more heavily than they otherwise would. That could come in handy.

‘The advice probably falls under black magic, since it was understood that the tips were not used to give their fellow human beings better sleep. It was probably rather a matter of deeper sleep making playroom for other acts of darkness,’ Haugen writes.

In the 1830s, just such a black book was found during repairs to Kviteseid church in the Telemark region.

There was the recipe for how to get everyone to sleep in a house: You should take the eyes out of an owl's head and put them in water.

One eye would float, and the other would sink. The floating one was to be placed together with a dead man's tooth over the living room door in the house where everyone wanted to sleep. They would sleep until the owl's eye and the tooth were removed.

The first night's dream

Another mysterious topic is dreams. Perhaps you have been annoyed by the jumble of dreams that don’t seem to make you any the wiser. You are not alone – people have experienced this since time immemorial.

“Maybe it’s worth trying out some of the old advice for true dreaming,” says Haugen – admittedly with a certain twinkle in his eye.

He has discovered both traditional and more quirky tricks to ensure a true dream.

An ancient piece of advice that bears repeating is one you have to file away for the next time you sleep away from home.

Counting window panes

Haugen describes this advice: “The first time you went to bed in a room you hadn't slept in before, you were supposed to count all the window panes. It was often dark, and it was only when you woke up the morning after that you found out whether you had counted correctly. And if you had counted correctly, then what you dreamt that night would come true.”

This advice can be found in sources going far back in time, says Haugen, even all the way back to fairy tale literature.

Some people might know what young unmarried women should do when Midsummer comes.

They must secretly pick seven kinds of flowers and place the flowers under the pillow. Then they are to dream about their future partner.

Unfortunately, this advice only works for unmarried women. And, Haugen points out, it's a long time until Midsummer.

Dream cake: Water, flour and an egg cup with salt

There is also advice that is appropriate for the cold time of the year: You could bake a dream cake for Christmas.

The dream cake was to be kneaded three Thursday nights before Christmas. In a recipe Haugen found from the Odalen traditional district, the cake was to be baked with flour, water and as much salt as an egg cup could hold. Anything that is salted has a biblical explanation, which Haugen goes into more detail on in the book.

The cake was to be baked in a round form and divided with a cross so that it had four sections. The initials of a married couple were to be written on the top two sections. In one of the bottom sections you should put your own initials. The fourth should be left blank.

“On Christmas Eve, you were supposed to eat the piece that contained your own initials and put the rest under your pillow. In this way, your future partner should appear in a dream – with a glass of water,” Haugen says.

Other people chose an easier option and ate three or nine salted herring before bed.

“So the question is then, whether the dreams could come true that way.”

You might want to try it yourself, if you dare.

Reference:

Haugen, Bjørn Sverre Hol. (2022). Søvn – ei kulturhistorie (Sleep – a cultural history). Skald forlag.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no