Black books contain tales of healing and summoning the devil. They were not meant to be shared

Black books provided everyday advice but were also steeped in mystery.

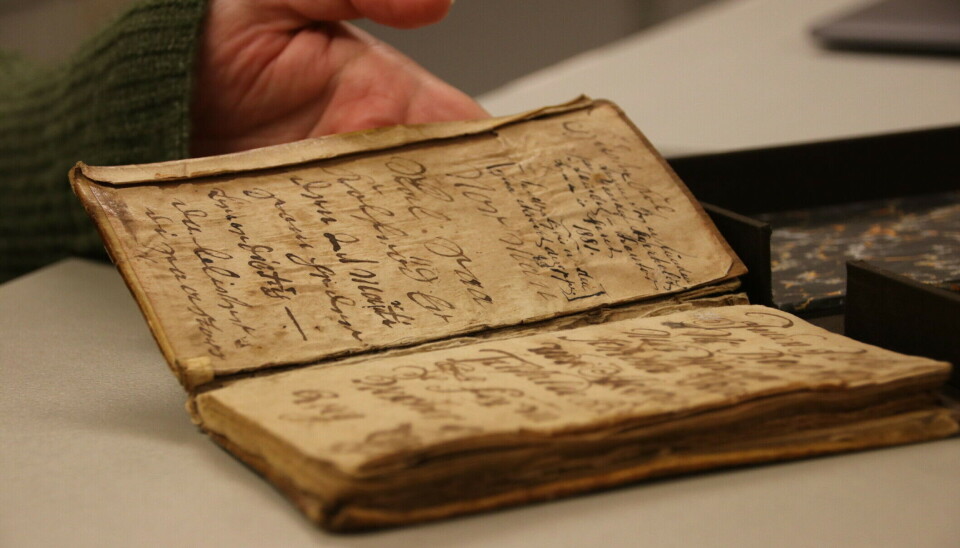

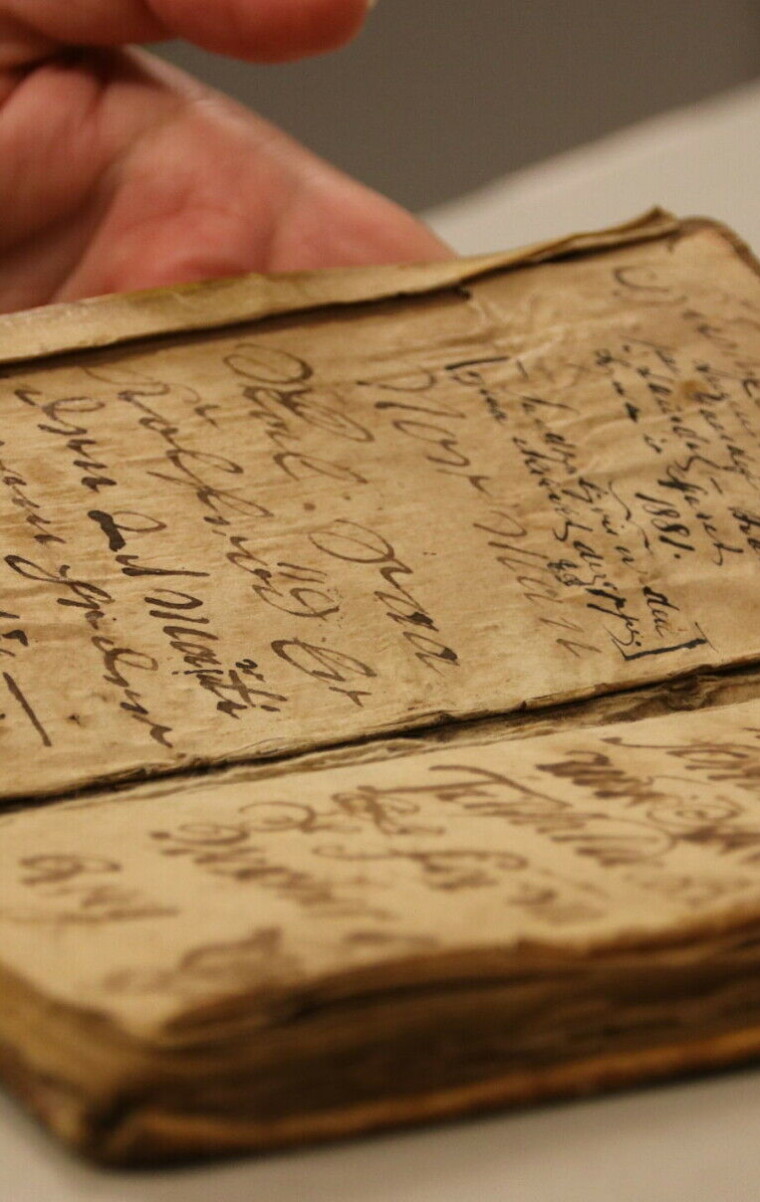

Therese Foldvik holds up a small, faded book, bound in leather.

Inside are fragile, yellowed, handwritten pages where secrets of the past have been recorded.

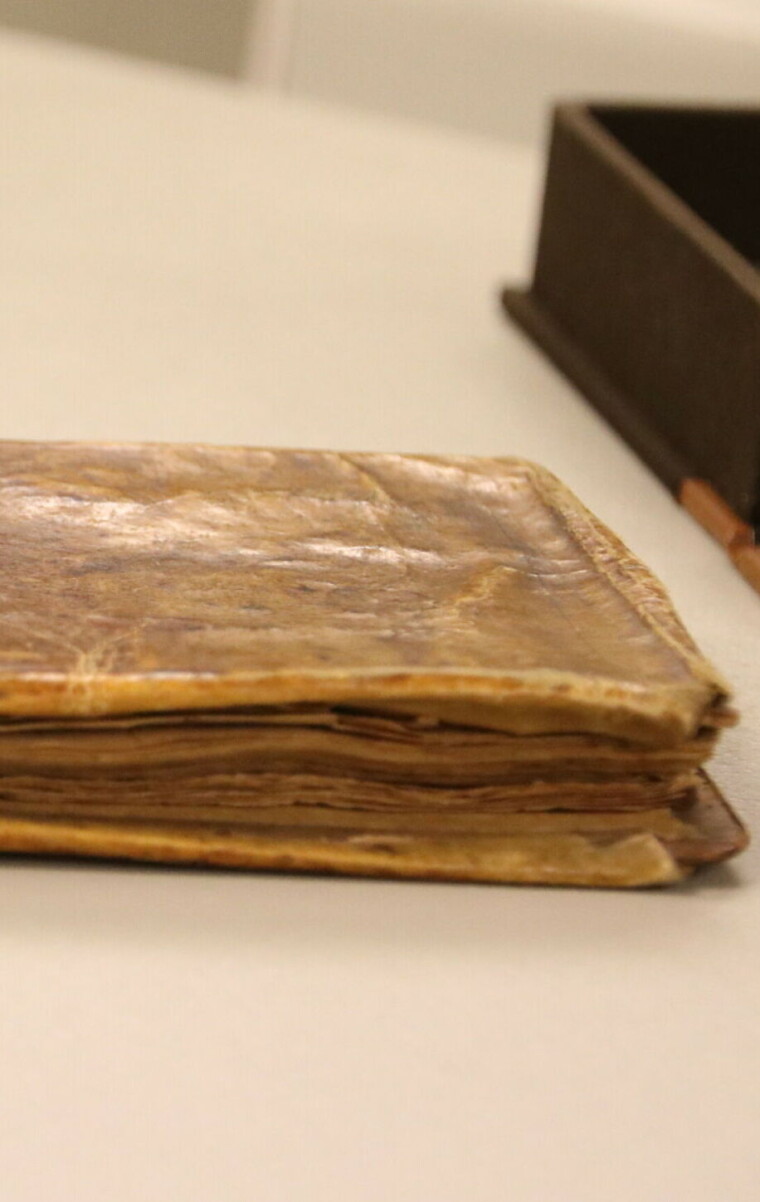

This particular book is an ancient magic text – a privately owned black book, also known as Cyprianus.

Foldvik and her colleagues at the University of Oslo's Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages have borrowed the black book.

To date, around 100 Norwegian black books have been registered, though many more likely remain in private collections throughout the country. The oldest known copy dates back to the late 1400s.

These black books offer a glimpse into historical beliefs, where magic was woven into folk traditions.

Most black books are unique, often handwritten. Owners commonly gathered recipes and remedies from various sources over time, sometimes spanning multiple generations.

The pages were a little jumbled inside the cover, but Therese Foldvik has sorted them.

“There's something really fascinating in here,” says Foldvik as she carefully flips through the book.

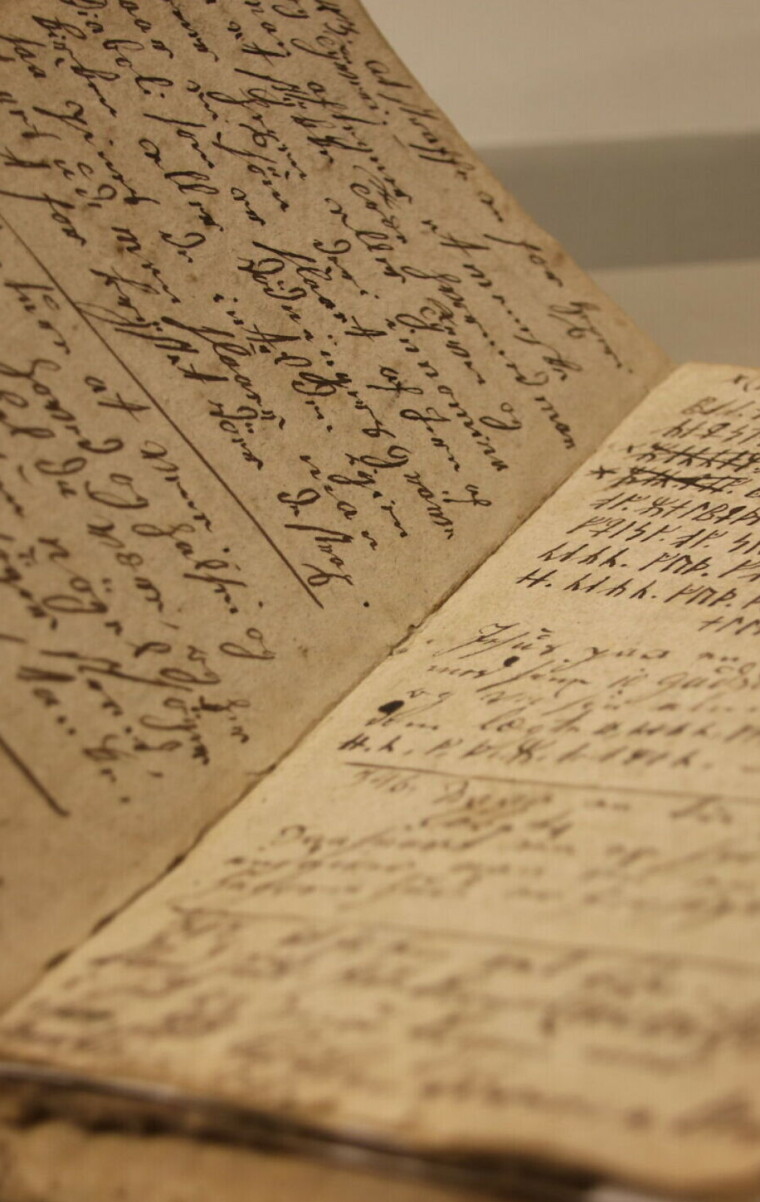

“There are runes.”

Foldvik can read the runes but will not reveal exactly what is written. The exact transcription has to be provided to the owner first.

“But it's a biblical reference,” she says. “It ends with amen.”

Likely kept in secrecy

The index at the beginning of the book is typical and shows that the books were used in daily life, says Ane Ohrvik, a professor at the University of Oslo and expert on black books.

“Owners could look up recipes to cure illnesses in both humans and animals," she says.

Other spells aimed to expose thieves or witches, bring luck in games and love, or reveal hidden truths.

However, these were not books you carried around or read from openly. They contained magical content, says Ohrvik.

“We have to remember that many of these black books were written during the time when witches were persecuted in Norway,” she says.

“Some of the content in black books involves summoning the devil. This involved invoking imagined forces and attempting to manipulate them to carry out tasks on one's behalf,” she says.

One example comes from a black book stored at the National Library of Norway, dated to the mid-1600s.

A multi-page incantation to make a thief return stolen goods concludes as follows:

‘I conjure you by the 7 fatherless devils, who are Beelzbub, Grogou, Sosten, Lupus, Largus, Beatrix, Hesefy: and request from you 7 devils that this thief, within 24 hours, be driven back with his theft in the name of Satan, Beelzebub, Belial, Astaroth, Bebel, Sisilo, Erebi, Bamale, Rebob, all devils in hell, amen.’

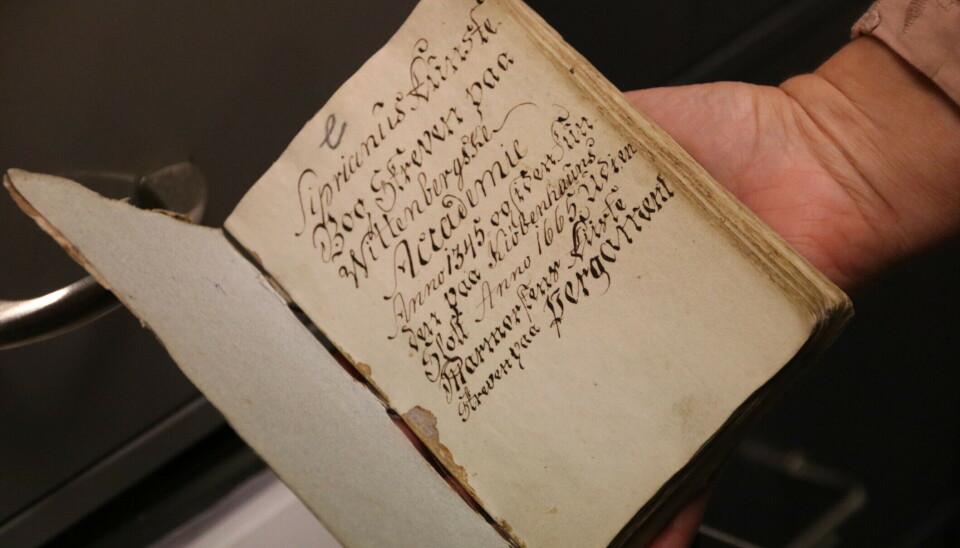

Therese Foldvik presents another privately owned book.

“I haven't started working on this one yet. It will be a surprise for all of us.”

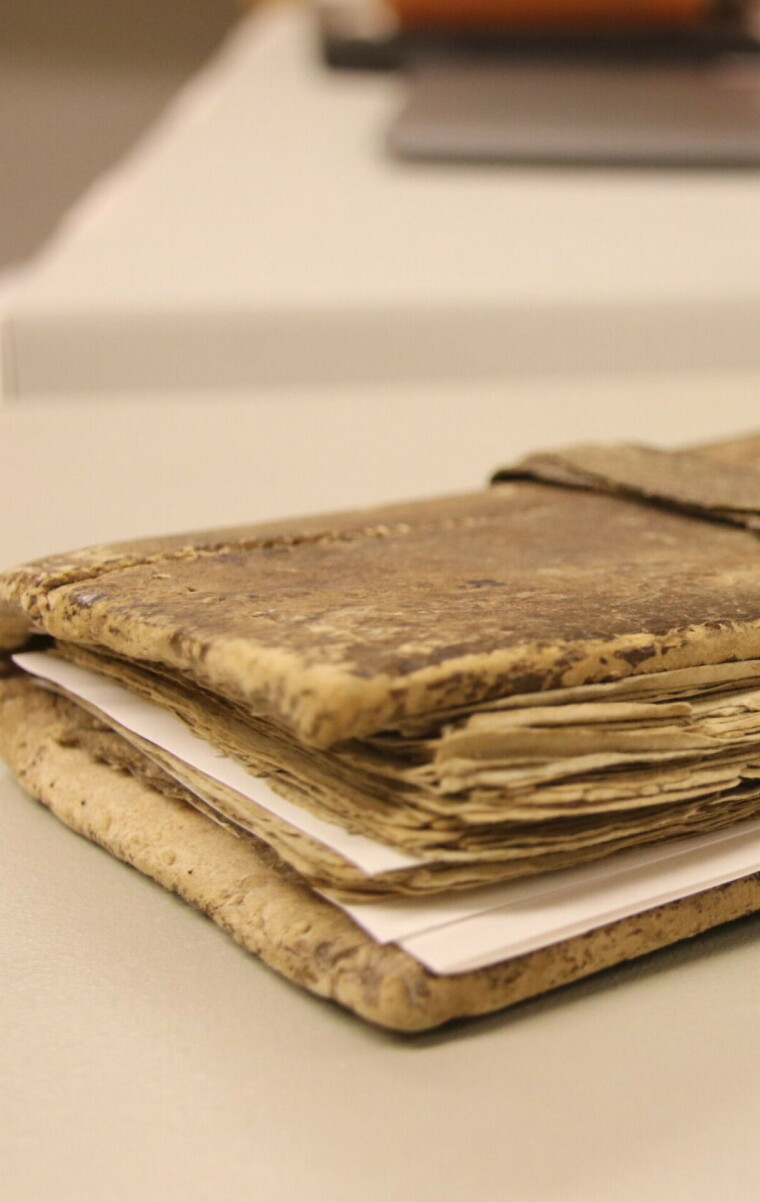

The book is intact and well-preserved, with its pages still bound together.

“You can tell from the handwriting that it's not easy to read.”

The book is written in Gothic script.

This script was used in Norway well into the 1800s and features an alphabet slightly different from the Latin one, says Ane Ohrvik.

The age of the books can be determined by identifying the type of Gothic script used, as the dates written in the books are often misleading, Ohrvik explains.

“They often backdated the books to appear older than they actually are,” she says.

Secret knowledge

At a time when there were few doctors in Norway, many so-called wise men and women practiced folk medicine. Documents show that at least some wise men were owners of black books.

“There could be rumours about someone being a black book owner. It might even strengthen their position in the local community or their reputation as a healer,” says Ohrvik.

Mette Moesgaard Andersen, a PhD candidate in religious studies at Aarhus University in Denmark, researches black books. At the University of Oslo, she is comparing Danish and Norwegian black books.

In the introductions of Danish black books, the content is often described as secret, but for those familiar with it, it is considered scientific knowledge.

“The introductions say that you shouldn't make a snap judgement if you find something you think is strange. The Norwegian books often contain a story about how Cyprianus gained his knowledge,” she says.

The dark sorcerer

The story of Cyprianus represents a kind of origin story for the black books.

“Cyprianus is one of the most notorious mythical figures of the Middle Ages,” says Ohrvik.

It is a tale of a dark sorcerer who realised he was practicing black magic and evil.

“He then converts to Christianity and becomes a devout Christian. However, Cyprianus retains a certain ambivalence,” she says.

Perhaps he still carries something of the dark sorcerer within him.

“I think the black books play on this when they are called Cyprianus. The book holds both good – and perhaps also evil,” she says.

Bat head

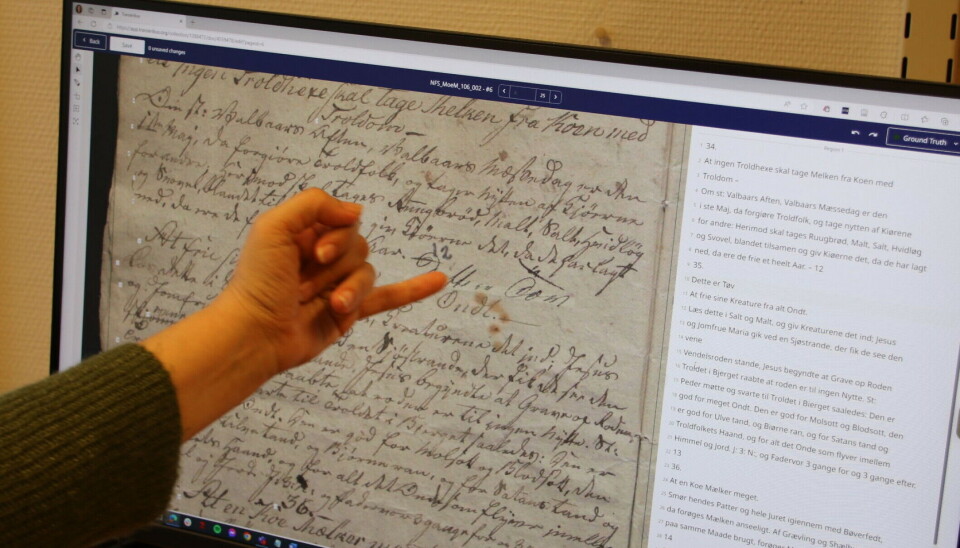

Therese Foldvik works on transcribing black books, which are uploaded to a platform called SAMLA, a digital archive.

She shows one of the spells she recently translated, which describes how to reveal secrets: Place a bat's head on the chest of a sleeping person, and they will speak of their deeds in their sleep.

At the bottom of the page, there are unknown words that resemble Latin.

“These can be noa words, a substitute for words perceived as dangerous. When used in the right contexts, they were believed to have magical power,” says Ohrvik.

Medicinal effects

Ane Ohrvik is involved in a project where researchers are examining plants used in folk medicine. Some plants mentioned in black books do indeed have medicinal properties.

“It's not just about faith but also experience-based knowledge that actually worked,” says Ohrvik.

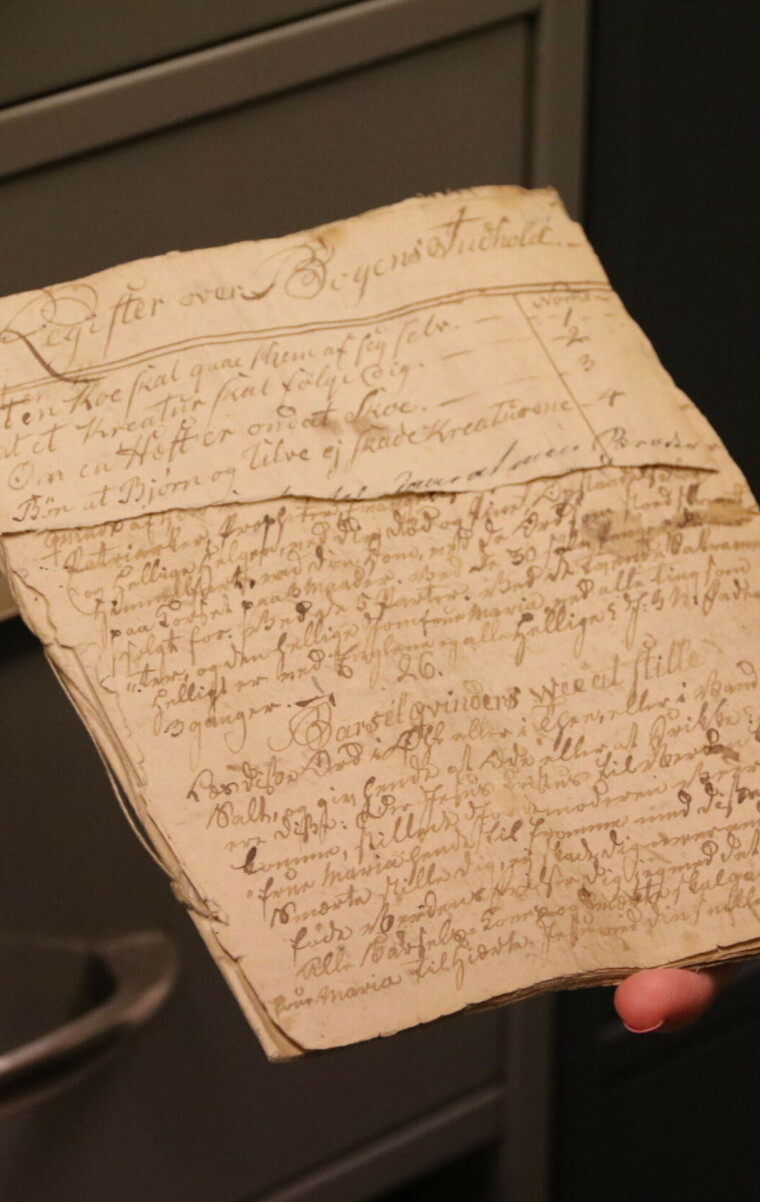

Ohrvik rummages through the filing cabinet and finds a black book in significantly worse condition.

This is often how they are found.

“They're often well-used.”

This book appears to have several writers, the researchers point out, which is quite typical.

Therese Foldvik uses a computer program that helps with the transcription of the handwriting. Then she has to fine tune the transcription.

She has just started translating pages from the thin booklet.

One of the spells describes how to protect cows from all evil with the help of a plant called common valerian. The spell is presented within a short story involving Jesus and Mary.

Foldvik points to a place on the page where a comment has been written in different handwriting.

'This is nonsense,' it says.

“There are actually comments throughout the entire book,” Foldvik notes as she flips through more pages.

‘Blasphemy,’ it says in one spot. ‘Intellect should use such a book.’

Medieval self-help books

Ole Georg Moseng is professor emeritus at the University of South-Eastern Norway's Department of Business, History and Social Sciences, and specialises in medical and health history.

He describes the black books as a kind of medieval self-help guide.

“They contain a lot of advice, such as how to get your horse to eat, remedies for stomach aches, or hair loss,” he says.

Little difference between folk medicine and doctors

Before the mid-1800s, the dividing line between folk medicine and academic medicine was extremely thin, Moss explains.

“Often, they completely overlapped. The faith healers of the 1700s were doing the same things as the doctors. They used herbal decoctions, plants containing toxins, and similar treatments," he says.

———

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

Related content:

Subscribe to our newsletter

The latest news from Science Norway, sent twice a week and completely free.