A dramatic love affair sparked the first witch trial in Scandinavia, 250 years before the witch-hunts started

Ragnhild Tregagås is the first person we know from the Norwegian Middle Ages who was accused – and later convicted – of magical activity.

Devil’s pacts, love magic, heresy, and curses.

This is what Norwegian women could be accused of in the 16th and 17th centuries, and the punishment was severe. Many were burned at the stake, some were beheaded, and others were banished from the country.

But accusations of witchcraft have also appeared in historical sources from the Middle Ages, several hundred years before the witch trials started in Norway.

Ragnhild Tregagås is the woman who in 1324 cast a curse over her secret lover and his newlywed wife in front of several witnesses at a vicarage in Western Norway.

And so she became the first woman we know of in all of Scandinavia to be convicted of witchcraft.

“The story of Ragnhild Tregagås has made a big impression on people in Hålandsdalen, surviving through oral tradition for seven hundred years,” says Therese Thuv, a researcher at Nord University. She has read historical court documents from Ragnhild's trial and wrote her master's thesis about her in 2020.

What did Ragnhild Tregagås do that made the bishop in Bergen sentence her for witchcraft?

Adultery and incest

Ragnhild Tregagås had a love affair with someone named Bård, despite being married to another man. Here, she already broke a law – the law against adultery.

But Bård was not just her lover. He was also her second cousin. This was considered incest and was also a violation of the law.

“In those times, engaging in adultery or incest was strictly forbidden. Relationships were not allowed with anyone within seven degrees of kinship,” Thuv explains. “Bård and Ragnhild were second cousins, so only three degrees.”

When Bård was to marry another woman, named Bergljot, Ragnhild did something even more illegal.

Cast curses from under the bed

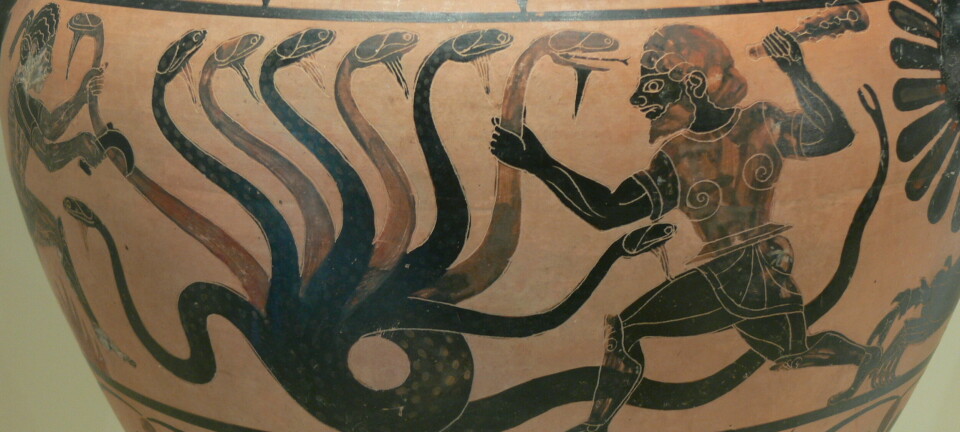

On the wedding night of Bård and Bergljot, Ragnhild hid somewhere in the room they were to spend the night. Under the newlyweds' bed, she placed five peas and five loaves of bread. She also placed a sword by the bed, before casting a ‘detestable incantation’ from her hiding place, according to the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia (link in Norwegian):

“I hurl the spirits of Gandul; one bites you in your back, another one bites your chest, and the third afflicts you with hatred and envy.”

The problem was just that this curse would not be fulfilled unless it was also said aloud in front of others.

The following day, she made her way to the local vicarage, facing a gathering crowd, with a rope wound around her hand. She declared loudly that Bård would fail to consummate his marriage to Bergljot because his member would be as limp as the rope she had coiled around her hand.

“This was essentially a typical case of jealousy,” Thuv says.

But with this, Ragnhild Tregagås committed yet another crime, a crime that would cost many women their lives in a brutal manner just a few hundred years later – witchcraft and magic.

Admitted everything after captivity

“It was quite the scandal,” Thuv says about the incident at the vicarage.

Ragnhild was summoned by Bishop Audfinn Sigurdsson in Bergen to explain what happened. Initially, she denied everything, but after some time in captivity, she confessed.

She was charged with having sexual relations with a relative, being a heretic, and spreading witchcraft.

“It was quite intense,” says Thuv.

Sources from laws

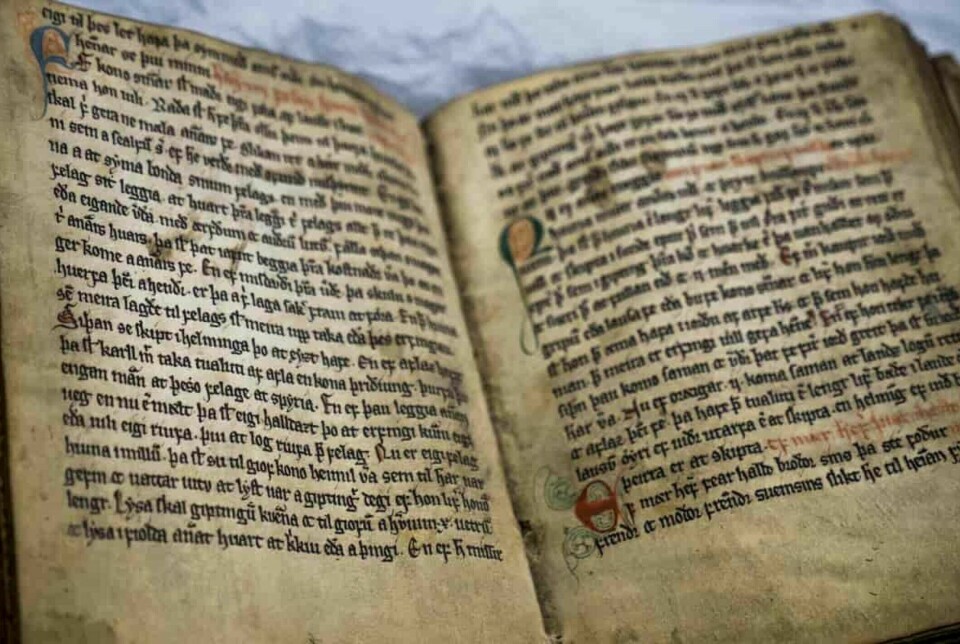

It is because of the old source material from the trial itself that we know so many details about what happened to Ragnhild.

Thuv has read the court documents from February 1325, when Ragnhild was brought to trial. They tell about the ecclesiastical court's handling of the case in addition to the verdict she received. These documents are preserved in Diplomatarium Norvegicum volume 9 and Regesta Norvegica volume 4.

“Documents from the Middle Ages were mostly written in Latin and therefore require a good knowledge of the language to perform a correct translation,” Thuv says.

It was the historian Peter Andreas Munch who translated them into Norwegian sometime in the 19th century. These are the translations Thuv has read.

She has also dealt with parts of King Magnus VI’s Code of the Realm from 1274 and the Younger Gulaþing Law from 1267, which mentions the prohibition against, among other things, witchcraft and adultery.

A quarrelsome woman

Thuv believes this story is unique in the medieval history of Norway.

“Ragnhild was an incredibly fascinating personality,” says Thuv.

Why Ragnhild got the nickname Tregagås, she does not know. She has some thoughts about why she got it, though.

“Tregagås is a name for someone who is quarrelsome, irritable, or has a bit of a bad temper. I thought she was a lady who didn't let herself be easily picked on and who caused problems. Norway at this time was a very male-dominated society, and if you were a lady with opinions and stood up for your rights, you might get labelled as difficult,” Thuv says.

A milder view of witchcraft in the Middle Ages

Back to the trial in Bergen in 1325, where the bishop was to decide what punishment Ragnhild was to receive.

“Originally, Ragnhild faced the death penalty. But in the Middle Ages, they had a much milder view of witchcraft than they did in the 1500s and 1600s. It was seen as superstition and that those who participated in it, did not know any better. It was perhaps more a sign that they were imaginative or immature,” Thuv says.

As a result, actions against supposed witchcraft were not as severe as they were during the witch hunts that occurred hundreds of years later, where accusations could lead to being burnt at the stake or beheaded.

Asked Satan for help

Rune Blix Hagen is a Norwegian historian and researcher at UiT the Arctic University of Norway. He specialises in witchcraft and sorcery trials in Norway.

“The story of Ragnhild is especially interesting because her case is the only one from the Norwegian late Middle Ages that resembles a witchcraft trial from the 17th century,” he tells sciencenorway.no.

The case includes, for example, diabolism, that is, asking for help from Satan, love magic, jealousy, and revenge.

“Unlike the later witchcraft cases, the trial against Ragnhild is handled by the clergy, and Ragnhild does not receive the death penalty – something she probably would have received if the case had been handled by secular court in the 1500s and 1600s,” says Hagen.

The word secular was used about what is related to the non-ecclesiastical, non-clerical world, that is, civil public law such as the district court.

Bread, water, and pilgrimage

Ragnhild was nevertheless punished.

The bishop sentenced her to fast on water and bread a couple of times a week and on certain holidays throughout the year. She had to do this for the rest of her life. She was also ordered to go on a seven-year-long pilgrimage to holy places outside Norway.

“It was not an unusual punishment for heresy cases in the Middle Ages, especially this part about doing penance by being sent on a pilgrimage to a holy place,” says Hagen.

But a solitary woman wandering was both dangerous and expensive at that time, according to Thuv.

“It was probably quite intense,” she says.

Seen as unaccountable

Before and during the trial, Ragnhild clearly showed that she regretted what she had done.

“The sources say she cried,” says Thuv.

Ragnhild must have sat in a dungeon for a long period, something that likely affected her during the trial, Thuv believes.

It was not just witnesses from the vicarage who stood forth in the case against her. She also had character witnesses. They said that Ragnhild had been moonstruck at the time of the crime and that she had not been in her right mind.

“The bishop took this into consideration,” says Thuv.

What happened to Ragnhild?

Since all information about Ragnhild is mostly found in the Latin documents from her trial, we know little about what happened to Ragnhild afterward.

But there are written sources in Trondheim that have been dated to a few years after the trial, says Thuv.

“A letter addressed to some monks from a person named Ragnhild has been found. She asks that they take care of her son while she is out on a pilgrimage. The little boy's name is Bård,” the researcher says.

Whether this is actually the same Ragnhild Tregagås, we may never know.

———

Translated by Alette Bjordal Gjellesvik

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no

References:

Thuv, T. Trolldom før trolldomsprosessenes tid. Saken mot Ragnhild Tregagås og senmiddelalderens syn på magi og trolldom (Witchcraft before the time of witch trials. The case against Ragnhild Tregagås and the late medieval view on magic and witchcraft), Nord University, 2020.

Hagen, R.B. Ragnhild Tregagås, the Great Norwegian Encyclopedia.