This pile of rubble is actually an ancient fort. Historians have discovered 450 of them around Norway

In times of shifting power relations during pre-viking times, many may have needed a stone structure for protection. But were they also used for other means?

Archaeologists and local historians have long discussed why people took on the difficult job of setting up stone and earth forts in many parts of the country.

About 450 so called hill forts have been recorded in Norway to date.

When archaeology as a discipline in Norway first began in earnest in the 19th century, hill forts were one of the first things researchers started studying. These structures, typically stones set in strategic locations, were called hill forts because it was thought that they must be a kind of defensive structure where villagers could seek refuge if their village was attacked.

This theory is still believed to be correct.

But perhaps these forts were used for something more.

From the year 200 to the year 600

Archaeologist Ingrid Ystgaard, from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) in Trondheim, is among the researchers now studying hill forts.

“Many people have interpreted these hill forts as defense related,” she said.

“What we can say with some certainty is that these structures were used in special situations, some of them probably conflict-filled situations,” she said to sciencenorway.no.

Ystgaard links most Norwegian hill forts to what is called the Late Roman Period to the end of the Migration Period, or from roughly the year 200 to about the year 600.

“But we know of hill forts that are most likely both older and younger than this time period,” she said.

“We also know of some examples of hill forts that were used during the Viking Age. But hardly any new forts were built in the Viking Age.”

A great deal of conflict

When the Roman Empire fell apart around the year 400, much of Europe entered a more conflict-ridden period.

Norway was no exception.

“The younger Roman Period and the Migration Period are times when societies in Northern Europe dramatically changed,” Ystgaard said.

“People as individuals could quickly amass great power during this time. But they could lose power just as quickly,” she said.

One new development during this period was that power became more strongly associated with individuals.

If we go back a little in time — to around the year 0 — researchers clearly find less evidence of individual power in Nordic society.

Power begins to be inherited

Norwegian society begins to change again with respect to power during the Merovingian Period (550-800) and approaching the Viking Age (800-1050).

During these times, it’s increasingly possible for power to be inherited.

This in itself does not free society from conflict, but brings conflicts up to a higher level in society. Conflicts are no longer solely local, and no longer as likely to be between neighbours.

That’s probably the reason why the need for local hill forts disappears, as Norway enters the Viking Age.

Were any of the hill forts actually farms?

The hill forts consisted of stone walls or earthworks. Sometimes long pointed sticks were stuck into the wall. These are called palisades.

The forts were often built so that at least parts of the structure had natural protection in the form of a steep slope. This made attack more difficult.

Ingrid Ystgaard points to the Swedish archaeologist Michael Olaussen (1948-2019) as one of the most interesting researchers when it comes to new perspectives on hill forts in the Nordic countries. One of Olaussen’s ideas is that some larger forts may have been more than just hill forts.

They may also have been fortified farms.

“These were places where people in power could live for several years in more protected areas during a turbulent time,” she said. “This may have been the case, especially where we see that there was access to water and arable land nearby.”

A study in Buskerud

The NTNU researcher believes that it will eventually be possible to conclude that some of the Norwegian hill forts may also have been permanent settlements.

In a master's thesis at the University of Oslo from 2012, Trygve Bernt followed up on precisely these thoughts when he examined a cluster of four hill forts in Øvre Eiker in Buskerud.

Bernt’s study points out how these four hill forts must have been used for more than refuge and defense. He shows how the forts can be linked to other uses.

His proposal is that these were multifunctional facilities, where the elite of the time in the Buskerud area may have met to trade. People in the forts may have bartered fine goods and objects that brought prestige.

The Buskerud forts may also have been used for religious and cultic purposes, Bernt suggests.

Many small villages

In contrast to larger and perhaps permanently inhabited hill forts, Norway also has many smaller hill forts, Ystgaard says.

A common feature she sees in the smaller hill forts is that they are often located next to old traffic arteries where people had to pass.

“These hill forts may have been more like checkpoints,” she said. “During a turbulent time, it may have been important to have control over people who were travelling. Maybe people had to pay a toll to pass through.”

Looting and warfare

Ystgaard also points out that this was a time when warfare was often mobile.

“Looting wars were a reality during this period,” she said.

Ystgaard's own doctoral dissertation from 2013 describes how the use of the axe may have changed Norwegian warfare precisely during this period in the Iron Age.

Until the disappearance of the Roman Empire, warfare had been conducted in a fairly orderly way in Germanic Northern Europe. People stood facing each other with spears, lances, swords and shields.

But around 1,500 years ago, the axe may have introduced more chaos to Norwegian warfare.

Were hill forts tactical?

Vegar Marius Thorsen Hyttebakk had a background from the Armed Forces when he decided to look at Norwegian hill forts from a tactical perspective a few years ago.

In his 2017 master's thesis, “A military strategic landscape analysis of hill forts in Steinkjer,” Hyttebakk examined 11 of a total of 14 hill forts in this Trøndelag municipality, which has the most known hill forts in the county.

The hill forts in Steinkjer are different. Nevertheless, Hyttebakk sees that two great advantages of building this kind of hill fort are that you are higher up than your opponent — and that you can seek cover yourself.

And the spears you tossed and arrows you shot would go farther than your opponent's.

In general, Hyttebakk concluded that the 11 hill forts in Steinkjer have good defensive properties.

Attackers would have to have a significant number of fighters to be able to defeat the people who defended these hill forts in Steinkjer.

Inspiration from Europe

Perhaps we should look beyond Norway’s borders when it comes to assessing what have long been thought of as Norway’s peculiar hill forts?

From Sweden alone, there are around a thousand known similar hill forts, called fornborgar.

Hill forts in Norway may also have been places where people in the years after the fall of the Roman Empire lived more or less permanently, as they may have done in British hill forts, in German wallburg and in Swedish höjdbosättningar/fornborgar.

Perhaps it was Norwegian mercenaries ‘at work’ in southern Europe who brought home the idea of erecting these fortifications?

Surveying county hill forts

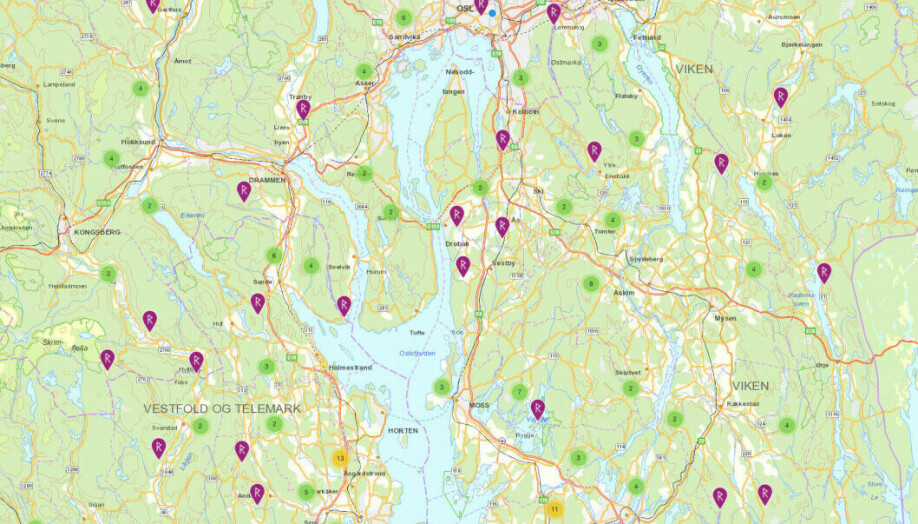

Viken County's Department of Cultural Heritage has now been out to survey and record 34 well-known hill forts in Akershus, 26 in Buskerud and 65 in Østfold.

The fortifications in Viken are mostly located on large bedrock outcrops with several really steep sections, the county archaeologists report.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Ingrid Ystgaard: Bygdeborger som kilde til studiet av samfunns- og maktforhold i eldre jernalder. (Hill forts as a source for studies of society and power relations in the older Iron Age) Primitive Tider, 2004.

Vegar Marius Thorsen Hyttebakk: En militærstrategisk landskapsanalyse av borger i Steinkjer. (A military strategic landscape analysis of hill forts in Steinkjer) Master’s thesis in archaeology at NTNU, 2017.

Trygve Bernt: Bygdeborgene: Tid for revurdering? En analyse basert på fire bygdeborger i Øvre Eiker, Buskerud. (Hill forts: time for a reassessment? An analysis based on four hill forts in Øvre Eiker, Buskerud) Master’s thesis in archaeology at the University of Oslo, 2012.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no