Vaccine resistance is nothing new.

What can we learn from sceptics of the past?

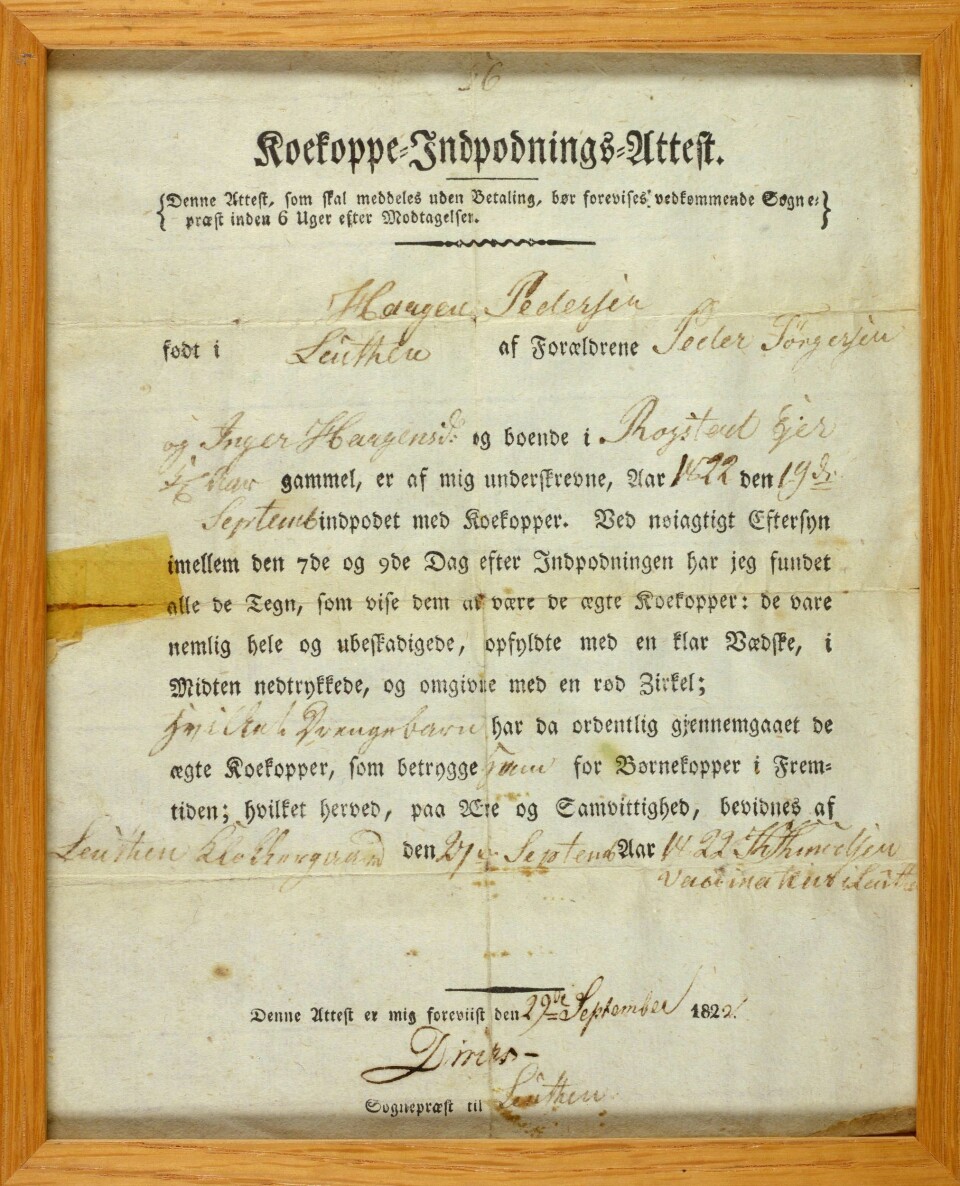

In order to get married in the 19th century, Norwegians had to present a certificate showing that they had received the smallpox vaccine. In the UK, the vaccine requirements were enforced even more strictly.

The idea that it’s possible to protect people from disease by giving them a small dose of the infecting agent is an ancient one.

As early as 3000 years ago, the Chinese made a powder from the crusts of blisters from people with smallpox. Healthy people were instructed to inhale it to protect themselves from the disease.

A slightly different method reached Europe in the 18th century via Turkey. The idea then was to prick the skin of healthy people with pus from smallpox blisters.

One of the first test subjects was Elizabeth Harrison. She was 19 years old when she was given the choice between being hanged or infected with smallpox in 1721.

But the first real vaccine came at the end of the 18th century.

Edward Jenner took fluid from the blisters of cows with a milder version of smallpox – and scientifically proved that this vaccine protected people from the deadly disease.

However, far from everyone welcomed the revolutionary invention with open arms.

Forced vaccination

“Vaccine resistance arose at about the same time as the vaccine,” says Hanna Nøkleby. She is a specialist in childhood diseases and a retired director at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH).

One of the reasons people became sceptical was probably due to how the new treatment was introduced.

“Vaccination against smallpox spread quickly, and several countries imposed laws that required people to be vaccinated,” Nøkleby says.

Opposition was particularly strong in Britain, where compulsory vaccination was introduced for poor people in the mid-19th century.

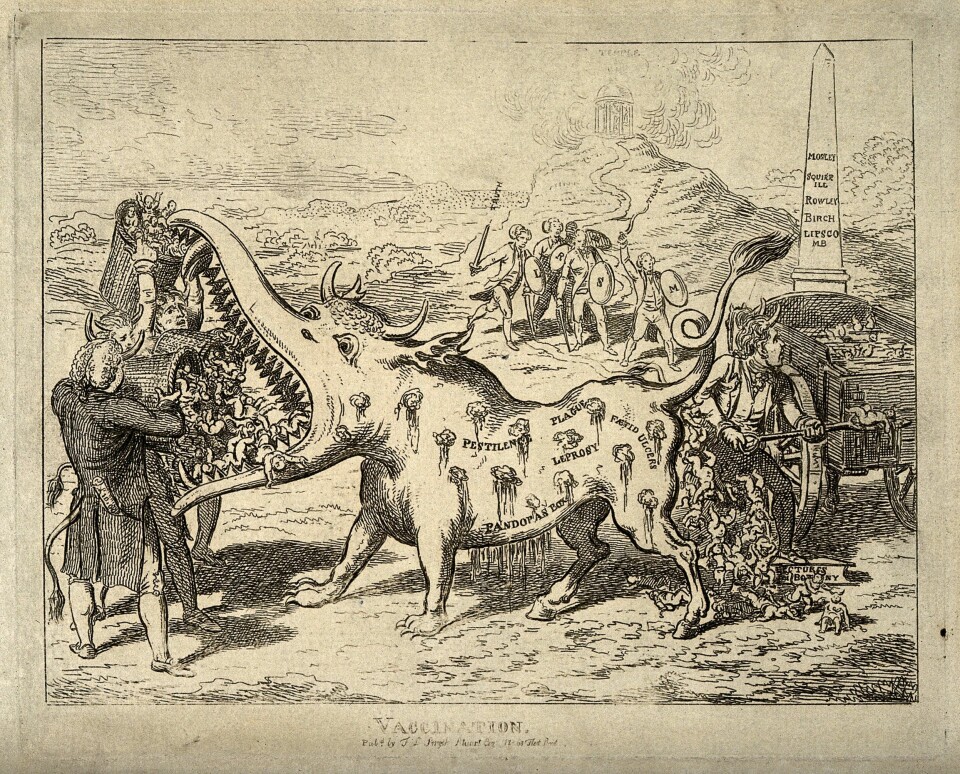

Demonstrations and anti-vaccine propaganda

Professor Steven King at Nottingham Trent University describes the mood as explosive in an article in The Conversation.

Many Britons demonstrated against the vaccines and distributed anti-vaccine propaganda. The authorities struggled to make headway with vaccinations because so many people didn’t show up for their appointments.

Although compulsory vaccination is not a reality in the UK today, King draws parallels to what could happen to people's attitudes towards corona vaccines if their concerns are not taken seriously.

He points to how the British Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, has called vaccine opponents “nuts.”

Resistance weaker in Norway

At the same time as the 19th century opposition exploded in Britain, Norway had also made vaccination compulsory, but without the mandate leading to the same reluctance.

“Denmark-Norway had a mandatory vaccination law already in 1810, which was quite early. The priest was required to check people’s vaccine certificates at their confirmation and wedding, and the ceremonies were not to be carried out if it was not presented,” Nøkleby says.

“But in Norway this wasn’t as strictly enforced so the resistance wasn’t as strong,” she adds.

Gives early sceptics a little credit

At the same time, we should perhaps ask whether vaccine opponents in the 19th century might have been a little bit right.

Nøkleby believes people had reason to be a little sceptical, even though there was no doubt that the vaccine worked.

Some became seriously ill or died from the vaccines, which contained live viruses. Since the vaccines were taken from the blisters of people with smallpox instead of from cows, another disturbing side effect also appeared.

Those who were vaccinated could in some cases contract other diseases in the bargain, Nøkleby says, including tuberculosis, diphtheria and syphilis.

Smallpox vaccine saved millions

At the same time, the smallpox vaccine unquestionably saved millions of lives.

When smallpox outbreaks occurred, many more unvaccinated than vaccinated people died.

“So in a year with a big smallpox outbreak, everyone who was vaccinated was no doubt very happy,” says Nøkleby.

“All the years there weren’t any outbreaks, the vaccine opponents probably had a point. So it's about seeing things in context,” Nøkleby says.

In 1741, for example, 700 children died of smallpox in Bergen alone, according to the Norwegian Institute of Public Health's (NIPH) infection guide for smallpox.

One to two children died each year from side effects

But smallpox became rarer as more people were vaccinated, until the World Health Organization declared the disease eradicated in 1980.

The vaccine had by then become a little safer. The virus was grown in a laboratory under sterile conditions but still contained live viruses and could have serious side effects.

One to two children died each year from side effects of the smallpox vaccine in the last years it was given in Norway, according to the NIPH.

At that point, it became less easy to agree that the vaccine was necessary.

Balancing the pros and cons

"Humans are less afraid to do something than not to do something. Doing nothing comes across as being indifferent,” says Nøkleby.

“Except when you feel very threatened. Then it looks different,” she adds.

Finding the balance between vaccination pros and cons is exactly what health authorities around the world carefully consider every time a new vaccine emerges.

The protection provided by a vaccine has to be strong relative to the risk of serious side effects.

Measles only dangerous for some

But whereas the authorities see the big picture, their assessments are not always equally convincing for everyone else.

Nøkleby cites the measles vaccine as an example.

Even though the disease is extremely contagious, it’s quite harmless for most people who get it.

“Measles is a disease where you have to look at the big numbers to understand that it’s dangerous,” Nøkleby says.

If a lot of people become infected, some will get seriously ill and die.

And unlike COVID-19, this is also a dangerous disease for children and adolescents – especially infants.

Autism side effect debunked

The MMR vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella is also considered very safe.

Among vaccine opponents around the world there is still a perception that this vaccine can lead to autism in children.

This rumour is alive and well, although the small study that showed a connection in 1998 has been withdrawn due to several errors.

And many large studies since have disproved that the vaccine is in any way linked to autism.

Gives credit to Norwegian health clinics

In Norway almost all children receive the MMR vaccine. Vaccine resistance may therefore seem greater than it actually is.

Nøkleby believes that the high vaccine coverage in Norway has several explanations. In particular, she highlights the role of public health nurses at all the municipal health care centres around the country.

“Public health nurses help parents of small children with a lot of different things. We regard them as our health professionals and not as an authority that’s telling us what to do,” she says.

This is not the case in all countries.

“For example, in Italy it hasn’t been as easy to get the measles vaccine. A number of doctors don’t want to give it at all. And people who actually wanted the vaccine didn’t always get it,” says Nøkleby.

Vaccine coercion reappears in Europe

Both France and Italy had fairly large measles outbreaks in the 2010s. Vaccination coverage was down to only 70 per cent, so the countries then introduced mandatory vaccination laws.

This broke with the Western European line in modern times, that receiving vaccines should be voluntary.

The new laws led to more people being vaccinated, according to Nature. Nøkleby is unsure how the measure has affected vaccine scepticism.

“The mandate was just as much for the vaccinators as for the people who were to receive the vaccines. But that's not how it sounds to people when it becomes mandatory,” she says.

Vaccine scepticism is much greater in these countries than in Norway.

A study from 2019 showed that as many as 33 per cent of people in France thought vaccines were unsafe, while only 6 per cent of Norwegians responded the same.

Vaccine resistance on social media

As the Internet has wiped out international borders, more people might be influenced by anti-vaccine propaganda now than when it was disseminated on paper in the 19th century.

During the corona pandemic, researchers have shown that anti-vaccine posts on Twitter can lead to fewer people getting vaccinated.

Therefore, Norwegian authorities need to take vaccine scepticism seriously, Nøkleby says.

“We have quite a few people in Norway who are hesitant and wonder if vaccines offer any benefits. So it’s very important for us to effectively inform and explain what we achieve with vaccines,” says Nøkleby.

Translated by: Ingrid Nuse