There’s a tiny little continent wedged between the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates

It's called Jan Mayen, and it's a microcontinent topped by a rather small island of the same name – the Norwegian volcanic island Jan Mayen – which sticks up above the sea surface.

The Earth's crust is made of seven large continental plates.

But the crust also contains several microcontinents. The vast majority are hidden far down in the deep seas.

However, the most typical microcontinent of them all may be Jan Mayen.

“There are many good arguments in support of Jan Mayen being part of a separate microcontinent,” says Sverre Planke. Planke is a geologist and researcher at the Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics at the University of Oslo.

Planke himself has studied the Jan Mayen Ridge, which is underwater, and found remnants of what geologists call continental crust.

Researchers from the universities in Bergen, Oslo and Iceland also believe they can establish that beneath Jan Mayen lies a thick crust that is typical of continents.

The world's oceans generally have a far thinner and much younger seafloor crust.

The continental rift ‘jumped’

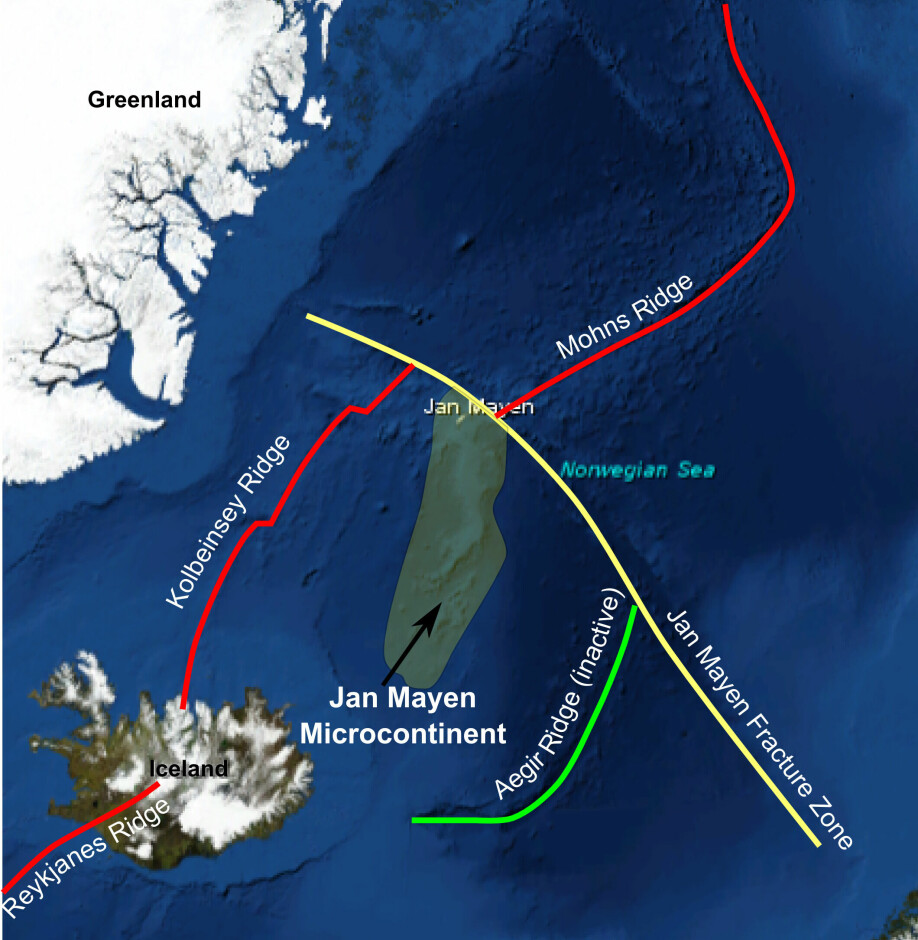

Greenland (the North American continental plate) and Norway (the Eurasian continental plate) began to separate 55 million years ago. At this time, the continent of Jan Mayen was first left on the Greenland side.

“But a few tens of millions of years later, it seems as if the crack that opened between the continents had ‘jumped’,” Planke said.

“The spreading axis jumped from the east side of Jan Mayen to the west side of Jan Mayen,” Planke said to sciencenorway.no.

The seabed that had spread out on the east side of Jan Mayen now began to spread out on the west side of Jan Mayen, between Jan Mayen and Greenland.

This may have begun between 40 and 33 million years ago.

Magnetism that records history

“The theory that the rift between the continental plates has ‘jumped’ from the east side to the west side of the Jan Mayen microcontinent is something we are working out now as we are studying this,” says Planke.

A powerful argument that supports this theory is something that scientists call magnetic anomalies. The researchers have mapped these in the deep sea.

These anomalies are a kind of memory that document in which direction the rock and the Earth’s large tectonic plates are moving.

In this case, this information provides information about in which direction the Atlantic is expanding.

A typical microcontinent

If Jan Mayen is actually a microcontinent — as much of the information researchers now have suggests — then the island Jan Mayen shares similarities with the Seychelles in the Indian Ocean.

Both the island of Jan Mayen and the microcontinent it sits on top of are long and narrow. This is quite typical for microcontinents, since they have often separated from a larger continental plate at some point.

The volcano at the top of Jan Mayen is also typical of microcontinents that rise above sea level.

Planke says that it has been difficult for geologists to study microcontinents, since they are mostly found in the deep sea. Without extensive drilling into the seabed, it’s difficult to document that a microcontinent exists.

Jan Mayen is the only reasonably certain microcontinent in the northern Atlantic Ocean.

Found five new microcontinents

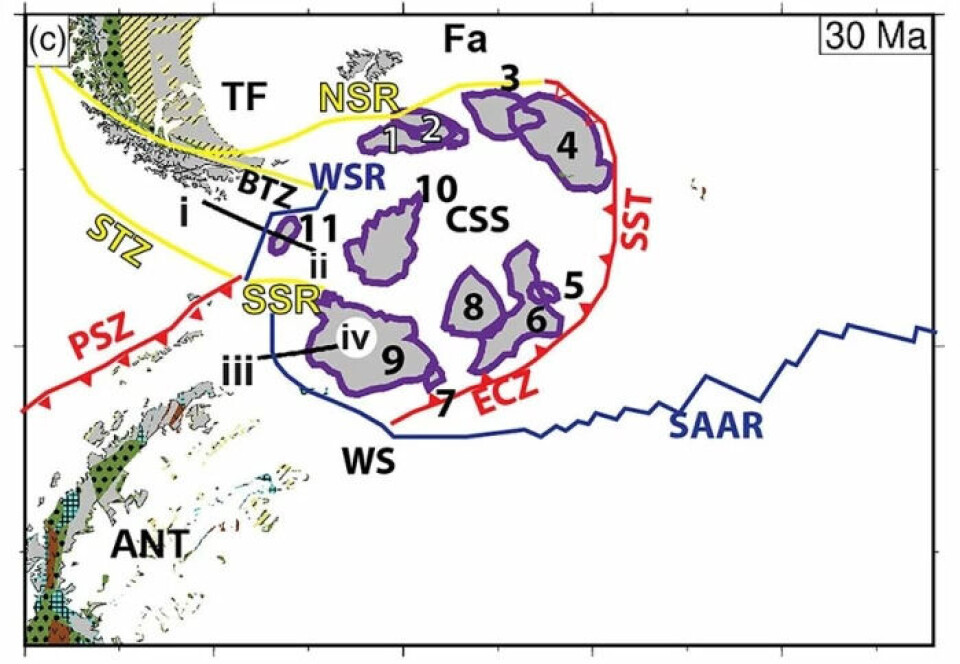

In a study published in 2020, researchers Joost M. van den Broek and Carmen Gaina at the Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED) at the University of Oslo identified and described five microcontinents.

The same researchers may have helped to explain some very fundamental questions about the Earth's surface.

Broek and Gaina think they can explain the formation of microcontinents by two processes.

- One process is when continuous movements of the large tectonic plates lead to the formation of cracks and weaknesses at the outer edge of the plates. That way, small bits can escape and come loose.

- The second process is even more important for the five microcontinents the researchers studied in their article, Broek and Gaina said. This involves smaller continental parts that are in the process of breaking loose and starting to rotate around.

The two islands of Corsica and Sardinia in the Mediterranean together probably also form a microcontinent. If you look at a map and use your imagination a little, you will see that the two islands together may have twisted to break free from today's France and Italy.

This process probably took ‘only’ nine million years.

This shows us a general feature of how microcontinents form: They tend to form quickly. It can happen in just a few million years, which is a very short time in the geological sense.

Another common feature of microcontinents is that they are formed while other complicated geological processes are occurring, both in the Earth's crust and down in the mantle below.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

References:

Stéphane Polteau et.al: The pre-breakup stratigraphy and petroleum system of the Southern Jan Mayen Ridge revealed by seafloor sampling. Tectonophysics, 2018. (Summary)

R. Dietmar Müller et.al: A recipe for microcontinent formation. Geological Society of America, 2001.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------