A volcanic catastrophe off the Norwegian coast likely explains dramatic global warming 55 million years ago

Never since has the climate on Earth warmed up so quickly — or been so hot. Researchers believe that the explanation for the rapid warming may lie off the coast of Norway.

Several new Norwegian and international studies about this mysterious global catastrophe will soon be published.

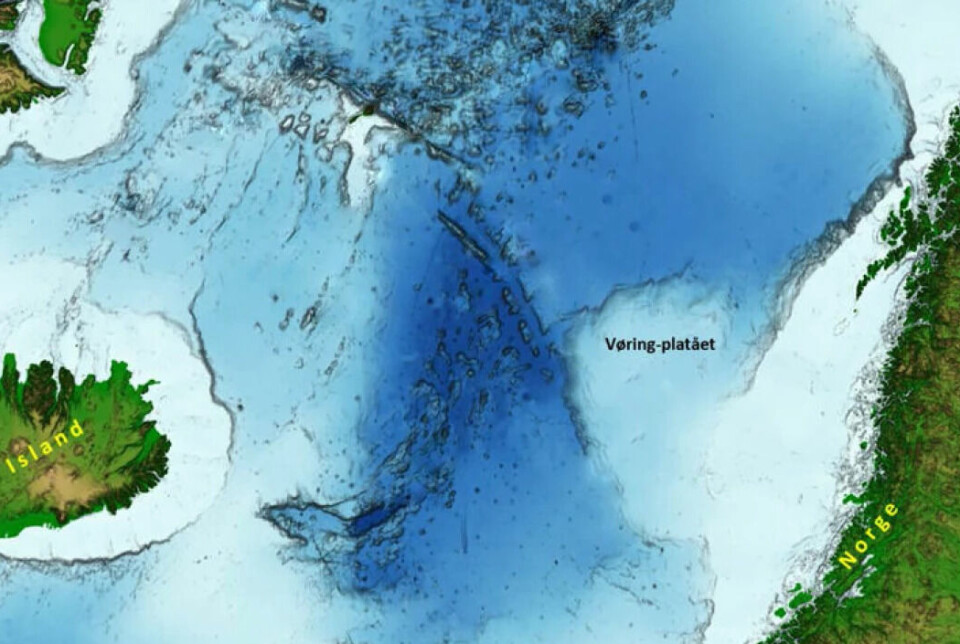

By all accounts, the studies will point to the Vøring Plateau just west of the town Sandnessjøen in Northern Norway, as the reason behind this dramatic climate event 55 million years ago.

Over a fairly short period, the average temperature on Earth rose by at least five degrees. Some researchers believe it may have increased by as much as eight degrees. This continued for almost 200,000 years.

The researchers find it particularly mysterious that the warm period began so suddenly.

30 researchers on an expedition

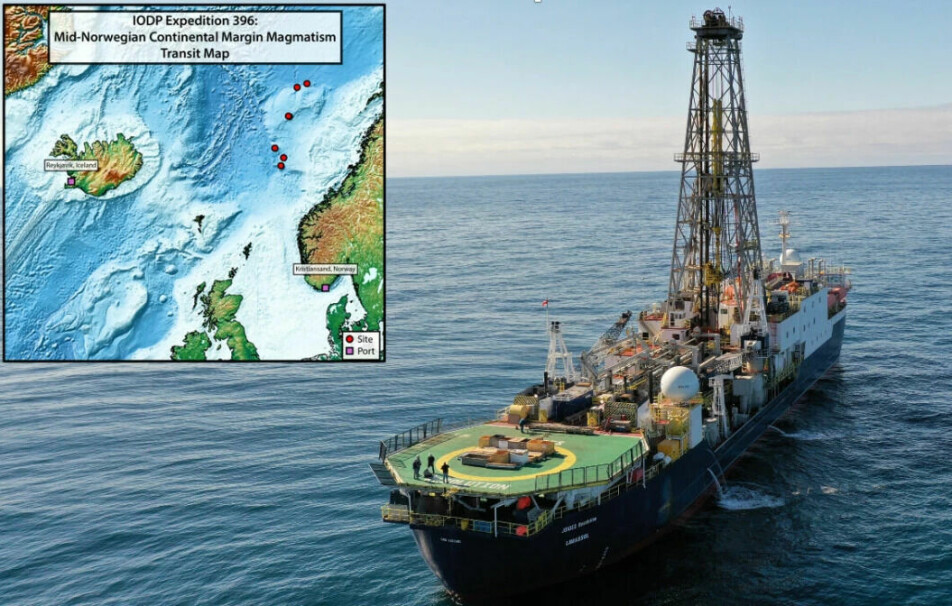

In August last year, the international research ship "JOIDES Resolution" set course for a 60-day expedition to the Vøring Plateau.

On board were 30 researchers and an equal number of laboratory staff. One of two chief scientists on the ship was the Norwegian geologist Sverre Planke.

“An important purpose of the expedition was to obtain core samples of the rocks on the Vøring Plateau,” Planke said to sciencenorway.no.

“Now we are even more certain that the plateau is an important part of a gigantic volcanic area that stretches from Lofoten down to Ireland. In the west it goes all the way to Greenland,” he said.

The rifting of Atlantic Ocean

Briefly explained, this event related to the opening up of the Atlantic Ocean.

Fifty-five million years ago, the process began where Norway (Europe) and Greenland (America) began to separate.

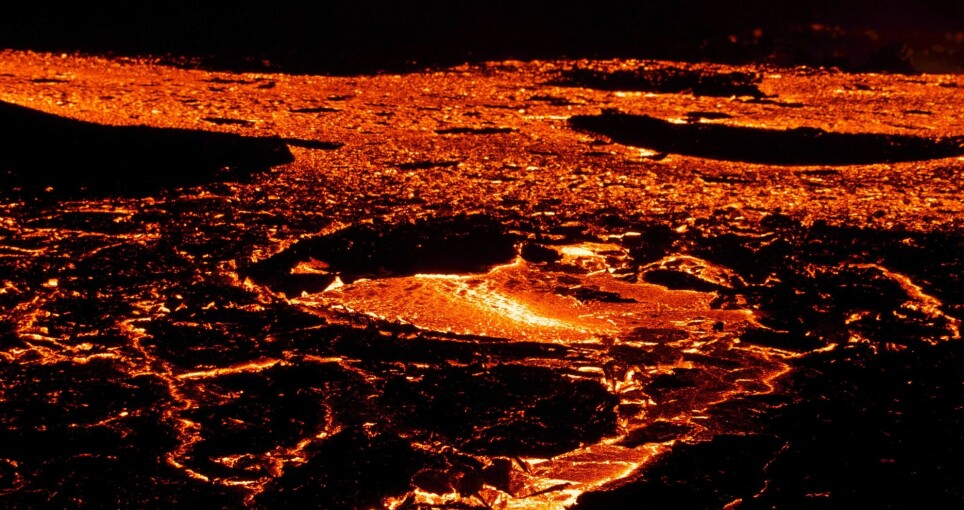

And it probably all started very dramatically, with all the lava (magma) that is now on the Vøring Plateau outside Nordland and Nord-Trøndelag, in central and northern Norway.

This was the event that led to the climate disaster.

As the rifting of the Atlantic continued for millions of years, more magma bubbled out from the Earth's interior. Kilometre-thick layers of lava on the Faroe Islands and Greenland are testimony to what happened.

“What is happening in Iceland today, with small volcanic eruptions, is a small but active remnant of the process of opening of the Atlantic Ocean,” Planke said.

Understand the causal relationship

The geologists who are examining the findings from last autumn's expedition will probably be able to describe in their upcoming studies a concurrence in time between the enormous amounts of lava on the Vøring Plateau — and the hitherto unexplained global warming 55 million years ago.

“The drill cores we obtained last year are very important for understanding causal relationships like this,” Planke said to sciencenorway.no.

“We now see that there is a clear overlap between the two events, the magma that bubbled up on the Vøring Plateau and the rapid global warming,” he said.

But the connection is not as simple as a lot of magma (lava) bubbling up from the Earth's interior leading to global warming.

A few hundred years of man-made emissions

“The hypothesis we are working with is that the magma heated up the sediments (layers formed from gravel, sand, clay and organic material) that were left on top of the magma. When this happens quickly and when the sediments are under high pressure, large amounts of CO2 and methane are formed in the sediments,” Planke said.

“When these greenhouse gases were released into the atmosphere, the Earth experienced severe and rapid global warming,” he said.

Planke and his colleagues have calculated that the emissions of greenhouse gases from the Vøring Plateau 55 million years ago correspond to a couple of hundred years of man-made emissions of greenhouse gases at today's levels.

The Earth's climate system usually does an efficient job of pushing excess CO2 into the world's oceans. But perhaps the greenhouse gases that resulted from the rifting of the Atlantic Ocean were so violent that the process did not work correctly.

The Atlantic opened up

Until 55 million years ago, Norway (Europe) and Greenland (America) were connected.

When the two huge continents began to move apart — and the Atlantic Ocean was in its infancy — the increasingly thin crust between them split open and released masses of red-hot magma.

Geologists call this form of volcanism fissure volcanism.

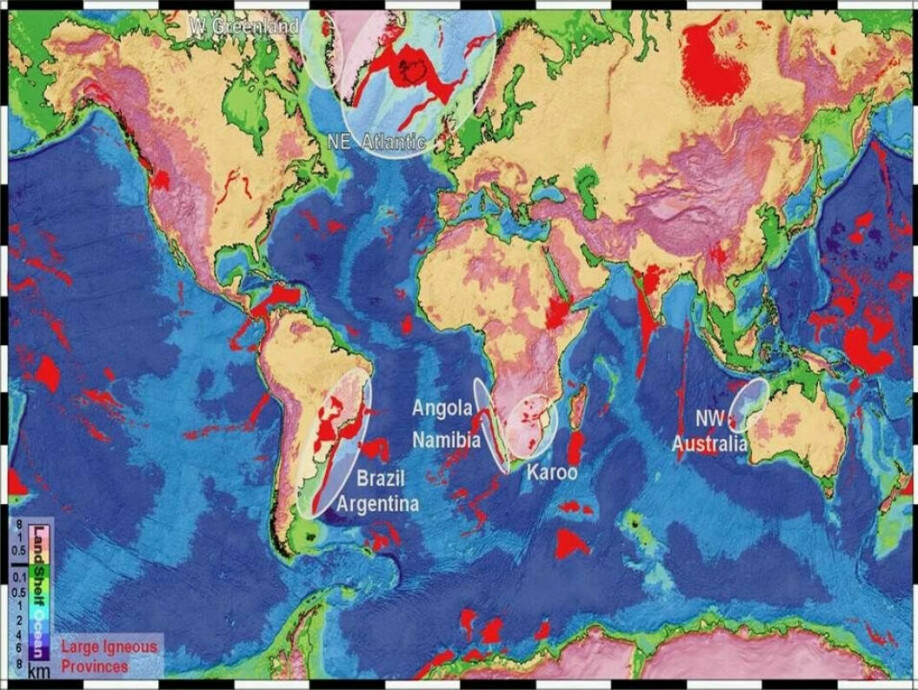

In several areas on Earth, rift volcanism has led to the formation of giant volcanic provinces.

This is a field of research in which Norwegian geologists, among others, have been heavily involved in recent years. The Centre for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED) at the University of Oslo has been central in this effort.

Six kilometres thick

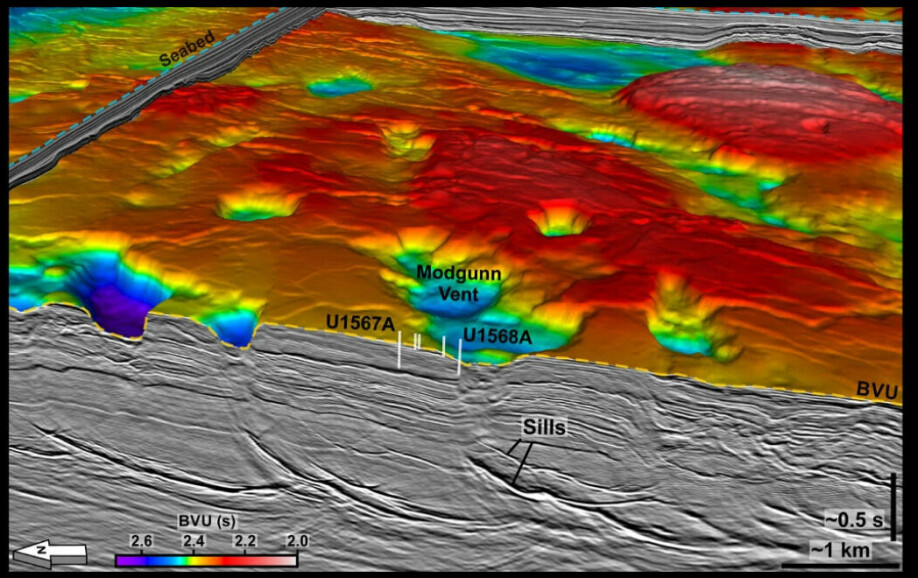

Perhaps the most interesting thing the researchers found during the expedition was a large number of pipe structures on the seabed.

“We drilled approximately 200 meters into one of these,” Planke said.

“This is how we discovered that this pipe structure was formed exactly at the time when the sudden global warming started,” he said.

The researchers now believe that the layers with remnants of magma from the Earth's interior out on the Vøring Plateau — what geologists call basalts — can be up to six kilometres thick.

The Vøring Plateau, it turns out, offers researchers a particularly good opportunity to study volcanic provinces in the world's oceans. Here, the sediment layers that lie on top of the volcanic basalts are perhaps only 50-200 metres thick. In other places with volcanic provinces, you have to drill through several kilometres of sediments to get down to the basalt.

“The sediments on the seabed are also a fantastic archive of remains of life that have arrived and life that has disappeared,” Planke said.

Lasted almost 200,000 years

The global warming period 55 million years ago is known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM). It lasted for almost 200,000 years.

In a research article published in the journal Nature Communications last year, a group of British and Danish researchers presented results that strengthened the hypothesis that greenhouse gas emissions from the Norwegian Sea were part of an explanation for PETM.

The researchers found that the concentration of mercury can be used to measure the volcanic activity. Both just before and during the PETM, they found mercury levels that were clearly higher than usual.

The researchers behind this study believe that global warming 55 million years ago caused the Earth's climate to pass what climate scientists call a tipping point, meaning the point where the effect of global warming becomes self-reinforcing.

A parallel to today's global warming?

Some climate scientists have pointed to the event 55 million years ago as a good analogy to today's human-made global warming.

If we understand the PETM and what the greenhouse gas event at the time led to, we can perhaps better understand what is now happening to the climate.

The good news is that most plants and animals on Earth appear to have survived the climate catastrophe 55 million years ago. Life did not perish in the same way as it did during the five or six great mass extinctions that are known to science.

No mass species extinction

The last major mass extinction on Earth occurred ten million years previous to this event, meaning 65 million years ago.

Most likely, an asteroid from outer space hit the Earth and caused the dinosaurs and likely many other animal species to disappear.

A hotly debated alternative hypothesis is that the formation of the Deccan volcanic province in India — which coincides in time with the asteroid impact 65 million years ago — created the Earth's last known mass extinction. Or could it have been a combination of the two events?

In any case, the animals and plants that lived on Earth during the climate catastrophe 55 million years ago may have been robust. After all, they had survived the dramatic mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs ten million years previously. But this is also just a hypothesis.

Large volcanic provinces

The formation of large volcanic provinces is still far from good news for animals and plants.

The most dramatic of all the great mass extinctions we know from Earth's history is the Permian-Triassic extinction, which took place 250 million years ago.

It occurred during the formation of the volcanic province known as the Siberian Traps.

The Siberian Traps today cover an area of two million square kilometres in central Siberia in Russia. The lava eruption that formed them may have lasted for a million years.

This volcanic event probably wiped out 95 per cent of all animal species.

The Earth became almost uninhabitable

After the Permian-Triassic extinction 250 million years ago, the Earth was more or less uninhabitable for several million years. Compared to it, the PETM 55 million years ago was almost a coffee klatch.

The situation now is that every year, humans release far more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere than volcanoes do. We actually emit more gases each year than occurred during the Permian-Triassic extinction and the formation of the Siberian Traps.

The PETM and the Permian-Triassic extinction may also give us a clue as to how long it will take for the atmosphere to cool again after large emissions of greenhouse gases.

References:

Sverre Planke et.al: Expedition 396 Scientific Prospectus: Mid-Norwegian Continental Margin Magmatism. International Ocean Discovery Programme, 2021.

David Bond: Sudden global warming 55m years ago was much like today. The Conversation, 2014.

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no