Cross stitch against German occupation: Is this Norway's first guerilla embroidery?

Caroline Moe embroidered. Astrid Løken spied. Women participated in resistance work during the Second World War, but are not mentioned in the history books.

When war broke out in Norway in April 1940, Caroline Moe bought linen fabric and black embroidery thread.

The teacher from Fjære near Grimstad, in south-east Norway, resisted the German occupation in her own way. While she worked on it, the tablecloth looked perfectly normal.

This kind of resistance needed to be undertaken as innocently as possible, according to Lena Sannæs. She is a historian and collection manager at the ARKIVET Peace and Human Rights Centre in Kristiansand. ARKIVET is the only existing authentic WWII Gestapo Headquarters in Norway.

During this time, women took needlework with them when they went to have coffee with friends or to meetings of the Red Cross or the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association. And there sat Caroline Moe with her crusade against war and for peace, even around members of Nasjonal Samling, the Norwegian far-right political party that was active from 1933 to 1945. The NS, as it is often called, was the only legal political party in Norway from 1942-1945.

“It was a little bit like giving them the finger. They didn't know what she was doing,” Sannæs said to sciencenorway.no.

Cross stitch against occupation

Sannæs thinks the tablecloth could be Norway's first guerrilla embroidery, a form of rebellious cross stitch embroidery. They became popular ten years ago, are often funny, but also political and critical, as Caroline Moe's tablecloth was. She may have been way ahead of her time.

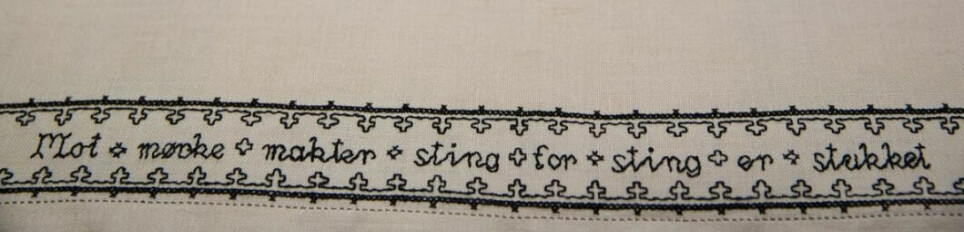

In the border around the tablecloth, it says in neat stitching:

Against dark forces, stitch by stitch is stabbed

In difficult times the doubt was never extinguished

A comforting belief in the day it will be used

As was meant for this cloth

“Caroline Moe probably made up the poem herself,” Sannæs said.

People in the local community knew about the project. When they asked how the tablecloth was going, it was a code for talking about the course of the war.

“The tablecloth was finished on Peace Day in 1945. And it has only been used once. That was when they celebrated Hitler's death,” Sannæs said.

Too small?

The cloth is part of ARKIVET’s collections from the Second World War. Some believe that the tablecloth is too small of a thing, and doesn’t demonstrate enough resistance, Sannæs said.

“But it's about maintaining your will to resist, and in those around you. The tablecloth becomes something to gather around. You’re defiant however you can be,” she said.

Many escaped to the forests to join the resistance to the Germans, but everyday resistance is also important, Sannæs said.

“If everyone who stayed at home didn’t resist at all, there would be no one left to fight for,” she said.

Women missing from the history books

Women also fought actively in the war.

Author Mari Jonassen has written the book "Norske kvinner i krig, 1939-1945" (Norwegian women in the war, 1939-1945).

Jonassen has gone through the reading list of history books from upper secondary school. Some of them don't mention women at all, she said.

And when she found pictures and text about women in these books, they were most often prisoners in concentration camps, housewives who provided food, or women who had fallen in love with German soldiers.

“The sum of this appears to be that women played no role during the Second World War,” Jonassen said.

She described some examples of women who had made active efforts in the war.

Spies, sailors and paratroopers

Signe Viborg Andersen took over as head of a Milorg group, after her husband was shot. Milorg was the name for the main Norwegian resistance movement. Andersen built up a communication section that consisted of only women.

Margit Johnsen, also called Malta-Margit, is one of Norway's most decorated individuals — with medals from Norway, Malta and Great Britain. Johnsen was a sailor during the war, and was torpedoed several times.

Dagny Sivlund was a partisan in the north. She made it over to the Soviet Union when the Germans came. First she was an interpreter, then she took a parachute course and became Norway's first female paratrooper.

Anne Sofie Østvedt and Astrid Løken were secret agents. Both were part of the leadership group of XU, the largest intelligence group during the war, with 1,500 agents under them, according to Jonassen.

Equal — but given women's tasks

“Norwegian women were involved in all forms of resistance and acts of war, including sabotage and planning liquidations,” Jonassen said.

Often they joined the resistance with a husband, brother, father or friend. The majority were single, young and working. Twenty per cent were housewives.

The women who took part experienced that they were equal to the men in the resistance, according to Jonassen. But they were typically given women's tasks, such as getting food and delivering messages.

Especially during the beginning of the war, many women were spies.

“The Germans did not realize that women were part of the resistance. That’s why they weren’t checked when they brought messages in prams and on bicycles,” Jonassen said.

The history books and encyclopaedias often state that Milorg consisted of 40,000 men at the end of the war.

10 per cent were women

“That’s not true, because 10 per cent of those who participated in Milorg were women. We should rather say that Milorg consisted of 40,000 men and women,” Jonassen said.

Exhibitions about the Second World War should include women, she said.

“But we have to work harder to find their stories,” Sannæs said.

As many women as men deliver objects and documents to museums, but it is often men's stuff.

“People bring us men's history. To put it bluntly: Everyone delivers things from their father,” Sannæs said.

One exception is women’s letters and diaries.

“Here, we can get a little closer and read these women's own thoughts and experiences. And there, the men are not as tough as they are portrayed on film,” Sannæs said.

Translated by Nancy Bazilchuk

———

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

------