We still don't know what causes heartburn

Thanks to the discovery of symptom-relieving medication, research on heartburn has dwindled. But the fact is, we still don't understand the underlying causes of this common ailment.

Surveys suggest that upward of 17 per cent of the Norwegian population suffers from gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, a condition caused by acid from your stomach flowing back up into the oesophagus.

The problem occurs when the sphincter muscle at the bottom of the oesophagus gets too slack and does not close properly.

People don’t necessarily bring it up in conversation. That burning fire behind the breastbone. Nausea. Belching. Sleeplessness. Or that acid and tightness in the throat.

A lack of restraint at a festive meal has no doubt on occasion brought on some of these symptoms for most people. But hundreds of thousands of us are afflicted by them even when they eat normally. Day in and day out.

“This disease has certainly become widely prevalent,” says Professor Jan Gunnar Hatlebakk at the University of Bergen, who has treated reflux patients and researched the disease for years.

May cause cancer

For most people who suffer from acid reflux, the consequences are limited to discomfort and reduced quality of life. But for a few the consequences could be disastrous.

The oesophagus is not designed to withstand the strong acid from the stomach. Constant acidic flooding from below can cause mucosal damage and result in ulcers and lesions.

In one out of ten cases, the cells of the oesophagus change. In the long run, this multiplies the risk of cancer of the oesophagus – a very serious form of cancer.

Lifestyle and medication advice

Research indicates that the incidence of reflux disease has increased significantly in recent decades, both in Norway and in other industrialized countries.

Although GERD ailments might not frequent discussion in the public arena, the issues are well known to medical staff. And help is available.

Doctors can offer both lifestyle advice and acid-neutralizing medications for patients’ symptoms. The only problem is that the available research doesn’t support all of this advice.

And the medications are not a good solution in the long run.

The acid-suppressing agents attenuate the symptoms without doing anything about their underlying causes. They only stop the discomforts in the oesophagus by reducing the normal acid level in the stomach by up to 90 per cent.

Undocumented advice

Lifestyle advice for reflux patients abounds:

Lose weight. Stop smoking. Avoid alcohol. Cut out coffee, chocolate, fat, peppermint tea, citrus fruits, carbonated drinks, spicy food and evening meals.

But scientific evidence is hard to find, with only limited studies and divergent results on the topic.

Ness-Jensen from NTNU has researched the disease and believes the main problem is overweight and obesity. “Several studies show that the risk of reflux disease increases the heavier you are. Patients who lose weight often get rid of their symptoms,” he says.

The increase in GERD since the 1990s has paralleled weight trends in the population, he adds.

Ness-Jensen also points to a study showing that some patients got better when they stopped smoking.

But this was only the case for patients of normal weight. Perhaps this is because obesity is a much more important cause, so the lesser effect of smoking becomes difficult to discern in overweight individuals.

No evidence for correlation with food and alcohol

A new research summary suggests that it may be wise to avoid meals just before bedtime, and that it can help to raise the head of the bed.

But when it comes to dietary advice, scientific evidence is sorely lacking.

Very few studies have tested whether patients are actually better off changing their eating habits. And research summaries have not found any apparent link to either alcohol or food.

But despite little scientific evidence supporting lifestyle advice, both Ness-Jensen and Hatlebakk believe that there may be reason to recommend lifestyle changes.

“Patients share their experiences with their doctor,” says Hatlebakk.

They say that the problems increase when they eat certain foods. And often the same items recur. Your doctor can share these experiences with other patients.

On the other hand, you risk giving the impression that people mostly have reflux due to a poor lifestyle and are to blame for their symptoms.

This does them a great injustice.

Hatlebakk says, “After working with these patients for 20 years, my experience is rather that they’ve cut out everything and often have a healthier lifestyle than the normal population. And yet they still have problems. That’s when they need to go on medication.”

And luckily the medications exist. Very effective ones no less, which in many cases remove both the symptoms and the risk of damage and cancer in the oesophagus.

Miracle pill

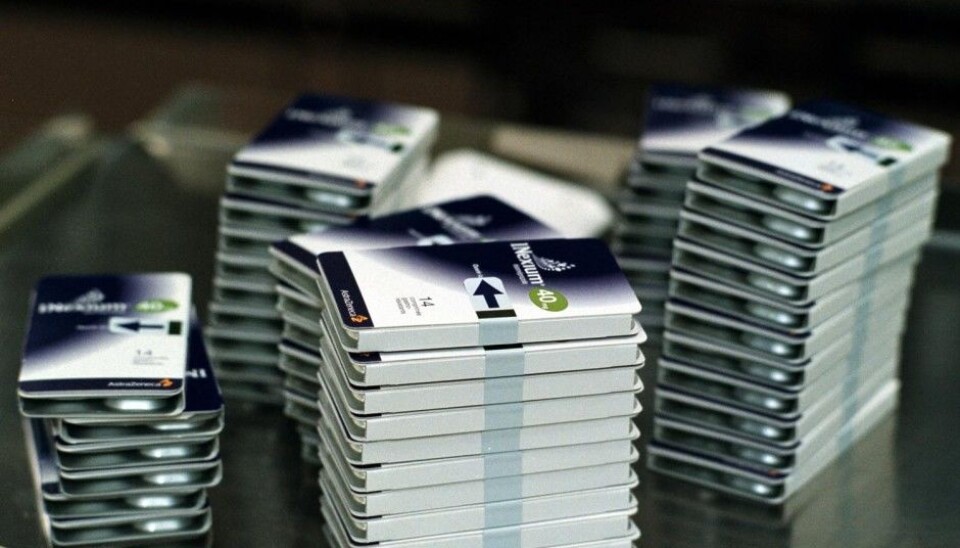

Around 1990, the first proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) appeared on the market. These drugs inhibit acid production in the stomach, and it soon became clear that they had a significantly better effect than the other medicines on the market.

The proton pump inhibitors also had few serious side effects. Finally, physicians had something to offer desperate patients suffering from constant stomach pain.

The use of PPIs has exploded. However, this has its problems.

Although proton pump inhibitors are generally regarded as safe, they do have side effects. Since acid reflux is often chronic, patients consistently on PPIs for years increase their risk of something going wrong.

“Gastric acid is important for the immune system, and when it disappears the risk of pneumonia and intestinal infections goes up. This can lead to reduced vitamin and mineral absorption in the intestines and result in osteoporosis and deficiency diseases,” says Ness-Jensen.

In addition, PPIs are presumably used by thousands of people who do not need them. Some patients remain on the pills longer than necessary, or could have used weaker drugs such as H2 blockers.

According to Hatlebakk, for a large group of acid reflux patients, PPIs have no particular effect. But instead of quitting, they increase the dose in hopes of improvement.

But a potentially far more serious problem in the long term concerns research. When the patent on the first PPIs was issued and pharmaceutical companies could create their own variants, the interest in GERD research started to fade fast.

“A little over a decade ago acid reflux was a hot topic among scientists,” says Hatlebakk, and “GERD dominated research congresses. But now it’s subsided.”

He believes much more research is needed in various fields, such as on the impact that various lifestyle factors actually have. And last but not least, research to identify the root causes of the problems associated with GERD in the first place.

Fat in the diet and ulcers

Hatlebakk identifies several possible explanations for the growing GERD problem.

Some researchers have suggested that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) could play an important role.

H. pylori appears to make the stomach contents less acidic. Since this bacterium is becoming less common among populations in industrialized countries, we might be missing out on this bacteria-elicited regulation of gastric acid.

However, Hatlebakk thinks more of another hypothesis: that the disease is linked to our diet, particularly to fat.

“A large meal that’s high in fat influences the sphincter’s closing mechanism and the movements of the stomach,” he says.

On the other hand, scientists have not found good evidence that fat in the diet causes acid reflux.

Nor is it easy to see how this hypothesis can explain the significant increase in the disease over the past 20 years, since research suggests that people in Norway are eating no more food or more fat now than a few decades ago.

Another issue that has become clear is that not all reflux cases have the same cause.

GERD and NERD

In the classical understanding of GERD, examinations will readily confirm patients' descriptions of the symptoms: when doctors peer down the oesophagus with a gastroscope, they discover the damaged mucosa, inflammation and sores.

The obvious reaction is to prescribe medication that inhibits stomach acid production, so that the injuries can heal.

But recent research has shown that over half of GERD patients appear to lack such unmistakable signs. The oesophagus and stomach look just fine.

Hatlebakk thinks these patients probably receive worse treatment than patients with erosive oesophagitis, which is where one sees sores in the oesophagus.

“These patients have often been sent home without treatment, with the message that they’re healthy,” he says. This is actually a separate subcategory of acid reflux, which has now been named NERD (non-erosive reflux disease).

So far, researchers still know little about why the two groups are so different.

Some research is showing that many patients who have the NERD reflux variant also suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which causes trouble further down in the gut.

PPIs often don’t provide adequate relief for these patients.

Recent research has shown that a low-FODMAP diet can help people with IBS. Hatlebakk said he and his colleagues have carried out a small study that suggests that a low-FODMAP diet can have a positive effect for this patient group.

But this is still a far cry from a possible treatment.

And with research on the underlying causes or alternative therapies at a low ebb, speedy help for patients who do not get relief from PPIs may be a long way off.

And a treatment that can cure the disease, rather than just control symptoms, seems even more distant.

-------------------------------------