Why do you get the stomach flu?

Why is it so hard to avoid a virus that forces us into the bathroom and makes us stick our heads in the toilet bowl?

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

It’s not the first time. Probably not the last either.

You don’t feel so well. The past half hour you’ve been out of sorts, somehow, and then it comes: Nausea.

Soon after that your entire dessert has taken a shortcut into the toilet bowl. That was just the prelude. Then the dinner and the starter make a hasty exit out the other end. And so it goes, with your stomach and bowels spewing out everything they’ve been in contact with. Was that a piece of the apple you ate last week? You feel the grim reaper is standing close by. But then it’s over for now.

But you aren’t safe for long. Nothing prevents the next epidemic of gastric flu from returning you to frequent trots to the loo. Why is this happening?

Why do we get sick? How come there are no vaccines that help? And why is it nearly impossible to avoid being infected?

Virus with a handicap

Most people know that gastric or stomach flu is caused by a virus.

“There are various types, but the most common are the noroviruses. Most of the outbreaks at schools, nursing homes and cruise ships are caused by noroviruses,” explains senior advisor Heidi Lange from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

It can be hard to limit the spread once these flu bugs are loose in a place where people crowd together. But oddly enough, the norovirus is far from being the disease-spreader that jumps most easily from one person to the next.

In fact, Lange says these viruses are competing with a handicap.

Noroviruses have to get from the inside of one person’s intestines to the inside of another’s. They need to hitch a ride with vomit or poop, which somehow has to end up in another person’s mouth.

It’s not necessarily an astonishing feat to jump from a child to a parent through a mess of vomit or a wet diaper. Viruses can also fly a ways on tiny aerosol droplets of vomit or diarrhea.

But how to reach a neighbour? Or perhaps even harder – a fellow passenger on the tram?

Whereas a cold virus can sit there enjoying itself just waiting to be coughed or sneezed onto a new victim, the norovirus has to hope for a handshake after someone forgot to wash their paws after a visit to the toilet.

Gastric flu viruses need to have nearly superpowers to survive. And that they do.

Extremely infectious

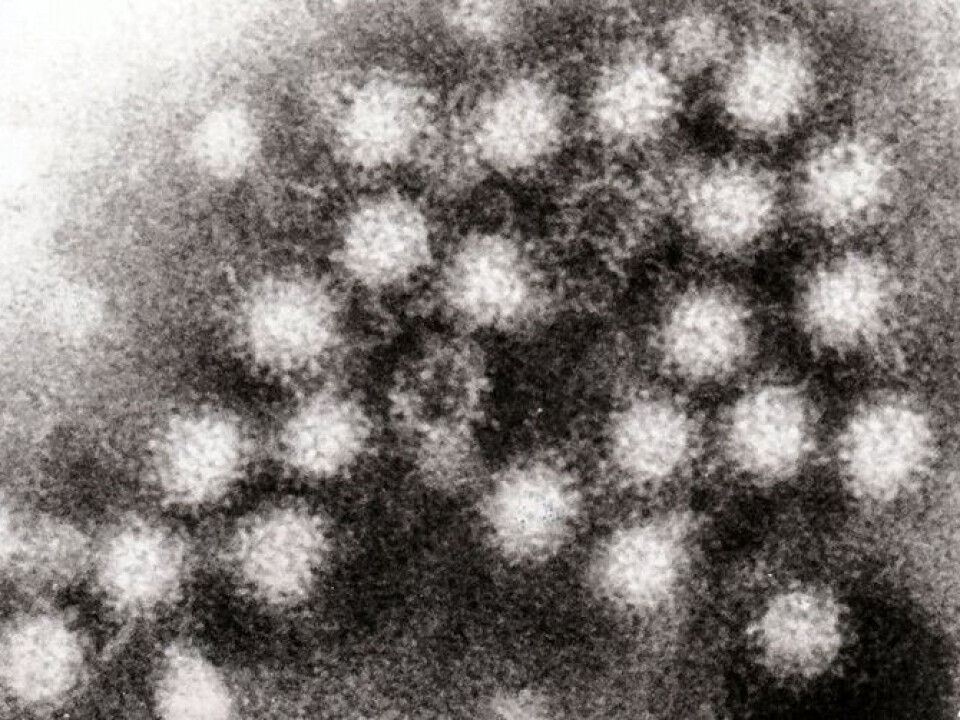

“There can be a billion viruses in a single gram of excrement from a person with gastric flu,” says Lange.

“All you need is get sick is 10 to 100 of them inside of you.”

Lange explains that once the virus gets a chance, it hooks onto one of the cells of the small intestinal wall. Then it makes a hole in the wall and squirts its own genetic material into the cell. This genetic material takes control and turns the intestinal cell into a virus factory.

Eventually the entire cell bursts open and adds a new generation of the virus to the intestine. These hordes attack more intestinal cells or they make their way out of your alimentary canal to new hunting grounds. In any case, armies of them escape – as fast as they can.

Symptoms – perfect for the virus

One of the things that makes gastric flu so unpleasant is your body’s urgent attempts to get rid of everything in the digestive tract. When the bugs are having their heyday we might wonder if one toilet per bathroom is enough.

“The virus probably stimulates the vomiting impulse. As for diarrhoea, it occurs when the intestinal epithelial membrane is damaged by the virus,” Lange explains.

"Both diarrhoea and vomiting are methods the body uses to rid itself of dangerous material in the stomach and intestines. But in this case the messy business is also in the interests of the virus," says Biologist Petter Bøckman at the Natural History Museum in Oslo.

“Watery stool is the most efficient medium. It can spout almost as if from a nozzle and form fine droplets. This is one problem in our modern times, where most of it ends in the toilet bowl. But think what it meant when we lived in caves! It wouldn’t take long before everyone in the cave was infected,” says Bøckman.

He thinks the viruses demonstrate a great evolutionary adaptation and use our repertoire of symptoms to their own advantage.

“The viruses mutate and develop fast. And they are constantly trying to find a good environment everywhere. When something works well they develop new variations and some of them will be even more effective," explains Bøckman.

It’s easy to imagine that a virus which can give us uncontrolled vomiting and diarrhoea will have more success than less unpleasant variations. As if that weren’t enough.

Unfortunately for us the norovirus has also developed other traits that make them appear to be undefeatable opponents.

Extremely robust

Stomach flu viruses are almost like the horrific aliens in movies. They can survive just about anything.

“Norovirus survives freezing and dehydration and temperatures up to around 60° C. Recent research also shows that an alcohol-based disinfectant doesn’t have much effect on them,” says Lange at the Institute of Public Health.

They can also stay in our bodies for a long time.

“We know that the virus can survive for several weeks at room temperatures and even longer if it is protected by dried up vomit or remains of diarrhoea, or finds itself in cold water. But exactly what its limits are is impossible to say because the virus can’t be cultivated in a cell culture,” says Lange.

The hardiness of the norovirus is the result of evolution.

“In order to spread through faeces and vomit they need the ability to survive in the environment for a long time,” says Lange.

With this capability the gastric flu virus isn’t dependent on direct contact between people.

Distributing the virus

When you get sick your body will start releasing the virus even before symptoms occur and also a few days after the diarrhoea or nausea is gone.

If you are careless with you hygiene and a hand washes after going to the bathroom you can carry the virus around the house and outside it. You can pollute the kitchen water tap or the handles on the tram. If you are preparing food for others the virus won’t have a long way to go before it’s inside new stomachs.

“The norovirus can infect us through contaminated foods, water and surfaces we come in contact with daily,” says Lange.

Food is mainly contaminated through handling and preparation. This is particularly a problem for food that is handled and eaten without additional heat treatment.

Ready-made salads and sandwiches come to mind. But globally it has been often detected on raspberries, probably passed on by berry pickers.

On the same lines, several kinds of fruit and vegetables can be the sources of infection. Lange herself has been involved in finding novovirus on imported lollo lettuce.

“The viruses probably come from sewage that has leaked into watering systems and been sprayed onto the vegetables,” she says.

A similar problem can arise when sewage comes in contact with seawater.

Oysters are known to be a food that can transfer norovirus. The molluscs can be contaminated from seawater and then we might decide to eat them raw on the half-shell.

All things considered, it would be virtually impossible to keep the norovirus at bay. This impression is reinforced after a mounting number of outbreaks that have occurred in recent years which scientists haven’t been able to explain.

The norovirus is responsible for huge economic losses and lots of individual suffering. So why haven’t we come up with a vaccine?

Downright uncooperative

“There are plenty of research groups trying to do just that,” says Lange at Norway’s Institute of Public Health.

Unfortunately the viruses are rather unaccommodating. The norovirus can’t be cultivated in a cell culture and this makes it harder to develop a vaccine.

When researchers in the lab are unable to experiment with a virus in a cell culture or use them on test animals, unravelling all their functions and finding any weaknesses can be perplexing.

In addition the norovirus comes in an array of varieties. These have different genes and various antigens – the part of the virus that our immune system recognises. Our bodies haven’t learned a good way of working up any immunity against these microscopic meanies.

“From infection experiments carried out abroad it looks like we can only develop a short-term immunity – less than six months – against the same variety of virus that made us ill,” explains Lange.

Scientists don’t know why.

The infection from one type of norovirus won’t protect you against another type.

Faint light at the end of the tunnel

Researchers are also in the dark regarding why some people seem to be more resistant to the virus than others.

Certain results indicate that blood type could have an effect – people with blood type O could appear to be less resistant than others – but lots of factors are involved.

“We don’t know enough to make any pronouncements about this yet,” says Lange.

Luckily there are a few glimpses of light. In December 2011 a research team published the results of a vaccination experiment on human subjects.

The vaccine was tested and appeared to have a good effect without significant side-effects. But according to the New York Times it will be a long time before a prospective vaccine can be launched on the market.

In the meantime we can do what we can to reduce the risk of infection. The key word here is plain, old-fashioned hygiene.

Wash those hands

“The most important protective measures against a norovirus infection are proper hand washes and good kitchen hygiene,” says Lange.

“Updated research shows that alcohol-based disinfectants aren’t so efficient against norovirus, so the Institute of Public Health recommends soap and running water. Mechanical scrubbing with soap and water is particularly effective for removing norovirus.”

If you have a contaminated mess to clean up you should try to wipe it up with paper towels. Then you can treat the area with something the norovirus detests – chlorine.

Lange recommends that we follow the concentration suggestions recommended on the bottle, for instance one decilitre chlorine to five litres of water, 1:50. Make sure this is a surface that can withstand chlorine. Contaminated surfaces of toilets, doorknobs, sinks and other spots that the virus could have come in contact with can be wiped with a similar mixture.

Another good idea is to try and keep your fingers out of your nose and mouth.

If this doesn’t help and you get the stomach flu there’s still a straw you can clutch: Your tribulations will soon be over and the virus is seldom serious if you are in reasonably good health.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Read the article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling