Psychology today – is it making our personalities impersonal?

Researcher wonders if neuropsychology research is improving our understanding of the brain but worsening our understanding of what it means to be human.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

The number of neuropsychology studies has increased dramatically over the last 50 years, according to Line Joranger’s recently defended doctoral thesis. And this increase concerns her.

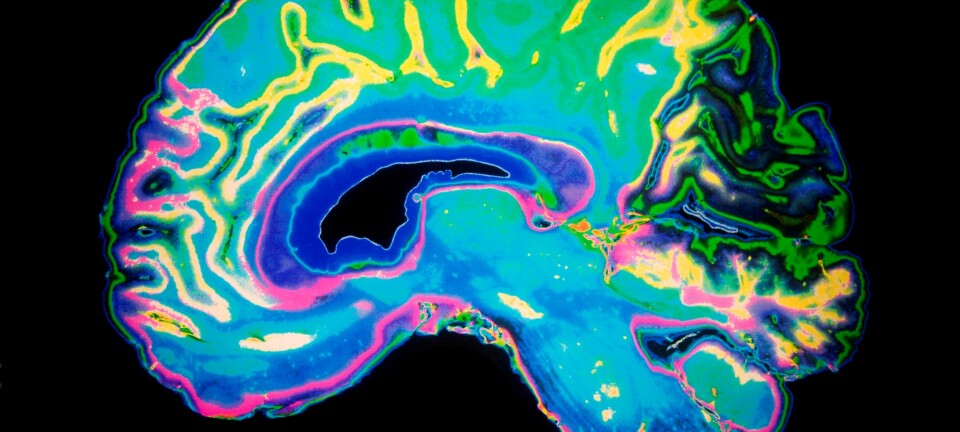

Brain research has given us countless answers and perhaps even more questions about how we think and behave. The research has also given us the ability to provide psychological diagnoses and treatment.

But Joranger believes this research gives a narrow view of who exactly you are and why you're doing what you're doing.

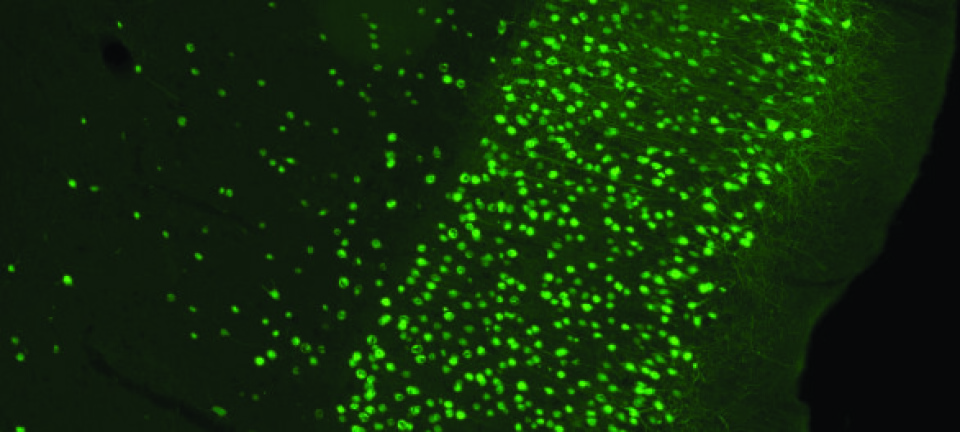

Neuropsychology is the branch of psychology that deals with the relationships between the brain and behaviour. So, based on what we know about the brain, we can predict how we will react to different situations.

“Human beings would need to become machines to be predictable,” Joranger told forskning.no.

Personality makes us unpredictable

Joranger believes that human behaviour is in many ways unpredictable. Cultural and social situations play an important role in how we behave. To work solely from the vantage point of brain research won’t provide a complete picture of what it means to be a human being.

The aspects of our behaviour that are shaped by things like culture, history and individual experiences— what she calls subjectivity—are distinct from the brain, she asserts. The fact that we experience things differently is part of what defines our personality.

Joranger believes that something even gets lost when brain research and science methods alone are used to map our behaviour.

“Although we may be able to identify where and what in the brain causes different behaviour sometime in the future, these pieces of information can never tell us the whole truth about a person, she says.

The brain is our personality

Professor Svend Davanger, from the Division of Anatomy at the University of Oslo, counters with a question. “If your personality doesn’t lie in the brain, then where else would it be?” Davanger.

He finds Joranger’s ideas interesting, but thinks there is no reason to believe that the explanation for our behaviour would be anywhere else than in the brain. Davanger explains that our experiences throughout life actually change how our brains are structured.

“Our brain is so complex that it’s fully able to accommodate everything within us that is affected by culture and our own life story,” he tells forskning.no.

Davanger emphasizes, however, that the neurosciences today don’t have all the answers. It isn’t possible to identify all the tiny parts of the brain and then to be able to say exactly who you are as a human being. But over time, the research will eventually be able to give us a pretty detailed picture of our personality.

So, if we give research enough time, we should be able to predict with fairly high accuracy how someone will react, even for an experience that only that person gone through.

But are we really willing to accept that our whole personality may eventually be mapped out by neat, scientific methods?

Natural laws amidst human complexity

“I think the fact that humans amount to more than what science can explain, is one of several reasons that people tend to exercise great resistance every time they’re faced with standardized methods and theories about themselves,” Joranger says.

Davanger thinks this is a simplification of how scientists work in practice. “There is no doubt that laws exist and are active in the brain, but there’s not much point to breaking them down into simple principles. Human beings are very complex,” he says.

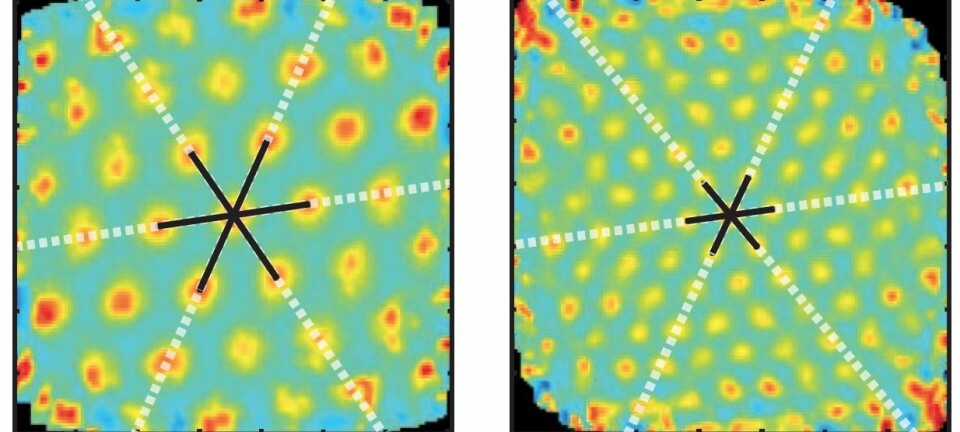

“But statistically speaking, to a large degree one can predict patterns of behaviour by a single person, based partly on psychological tests and brain scans,” Davanger adds.

Need for caution

Joranger recognizes that neurology has been important for psychiatry. Yet she warns against using this knowledge exclusively when psychologists and psychiatrists help their patients.

“If the aim is to understand and perhaps also to help others, this knowledge can’t stand alone. The human being is infinitely more,” she says.

She cites the debate over the so-called “packet stream,” a pre-designed template to be developed for providing psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Joranger fears that ideas from neuroscience will strengthen this concept, and that in all the myriad details a person’s individual needs will disappear completely.

She is calling for caution and for psychologists to also keep sight of the individuals who are sitting in front of them.

Davanger doesn’t disagree. But he does not recognize the psychiatry that Joranger is describing. “In practice,” he says, “you make a diagnosis based on an assessment of several things - behaviour, conversations with the patient and with relatives. Brain scans serve more as a supplement to this assessment”.

He strongly believes that if one is to help patients with their mental health care needs, being able to recognize how people react will be useful in figuring out how best to help that person.

Multiple perspectives important

Joranger says she isn’t against neuroscience research, but she would like to see researchers in the field reflect more on why neuroscience research has become so popular, and what concepts and rules guide the research.

She encourages researchers in psychology and neuroscience to use knowledge from the humanities, such as the history of ideas or philosophy, to get different perspectives.

“The goal is to discern whether we’re influenced by beliefs and rules that limit, rather than enlighten, our understanding of being human,” says Joranger.

Davanger is also open to using other disciplines to bring in new perspectives.

“I agree that cultural factors and humanistic perspectives are important for understanding a human being. But I don’t see any contradiction between the humanistic perspective and the neuroscientific perspective. On the contrary, I would say that they are two sides of the same coin,” he says.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no

Scientific links

- Line Joranger: The World of Psychiatry and the World of War: Foucault's Use of Metaphors in Le pouvoir psychiatrique. History of European Ideas, 2012.

- Line Joranger: Mental Illness and Imagination in Philosophy, Literature, and Psychiatry. Philosophy and Literature, 2013.

- Line Joranger: Development of the Self in Society: French Postwar Thought on Body, Meaning, and Social Behavior. The Journal of Mind and Behaviour, 2014.

- Line Joranger: Karl Jaspers' Interdisciplinary and Dual psychopathology. Journal of the Nordic Society for the History of Ideas, 2014.