Chronicles for the comatose

Norwegian nurses keep diaries for their patients who are in comas. When patients wake up these special journals can help them cope with traumas.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

One of your worst nightmares has happened:

Following a horrible car accident, you slowly gain consciousness in an intensive care unit (ICU). Maybe you’ve been there a day. Maybe a whole month. Everything after the accident is a blur of sensory perceptions you just can’t grasp.

Such experiences can continue to haunt patients long after their release from hospital. Chance sounds or smells can trigger subconscious memories which create stress, confusion and anxiety, even if a patient’s physical health has returned.

Norwegian nurses have worked out a simple method for helping patients deal with such traumas:

“We recommend that Norwegian intensive care nurses keep diaries for each patient, so that he or she can better comprehend what has happened,” says Sissel Lisa Storli, who heads a group conducting near-patient nursing research at the University of Tromsø.

“Patients struggle to understand the burden they’re bearing, even after they’ve been released. We’ve seen that these diaries can be of great help,” she says.

Fragments of reality are confusing

Along with colleagues in other hospitals and in the Norwegian Nurses Organisation’s group for ICU nurses, Storli has developed a guideline proposal for how nurses in Norway should keep such diaries.

Their recommendations are based on Norwegian and international studies and on the experiences nurses have with such diaries.

“Patients at ICUs experience something distant from reality. Some say they have been on trips in the mountains or out in a boat, while others live on in whatever reality they were experiencing prior to the accident. These are often very emotional experiences,” says Storli.

All of them tell Storli that impressions from the hospital can filter into their dream world:

“I met a patient who put it aptly: ‘When your head is knocked out, you experience the world in other ways, but you still retain memories from your experiences. You’re present and sensing things but it’s on a wholly different level’.”

Maybe you share the room with an 80-year-old man, but all you sense are sounds on the other side of a curtain. Or maybe a mother is singing to her child in a neighbouring bed.

“Only fragments of such impressions seep in, because the patient cannot sit up and investigate what’s happening. These things get stored on a preconscious level. They aren’t clear memories, but rather they’re experiences that can afterwards be recalled through sounds and other sensory perceptions,” says Storli.

“You seem to be physically restless”

The recommendations, which were issued last December, begin with a description from a patient diary:

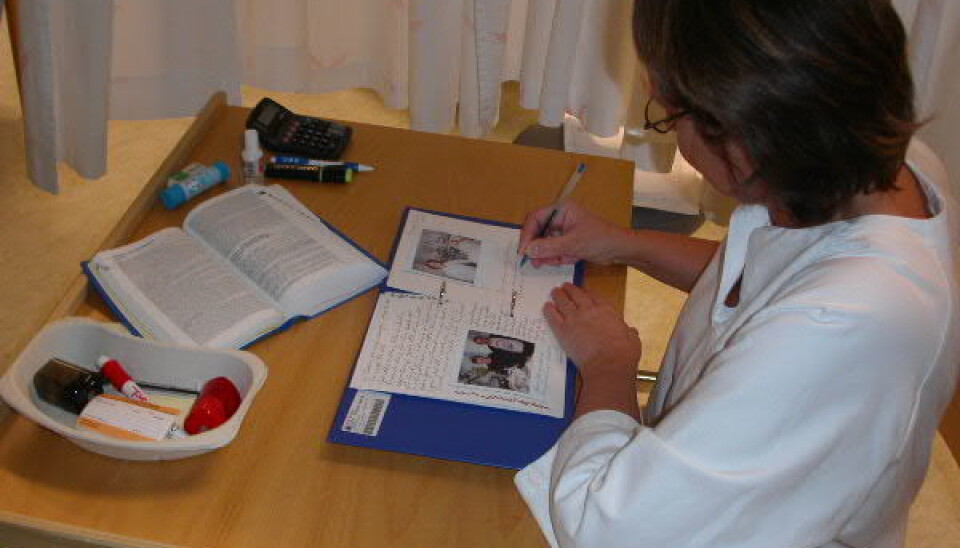

Today you’re sufficiently awake to look at us for several minutes at a time. But you seem to be physically restless. And there’s something you want to tell us which we’ve been struggling to understand. In this photo you see when I’m trying to fathom what you were trying to say (…)

And now I think I understand some of your words: “Outboard motor – turn off the outboard motor …” And you nod when I repeat this, and I tell you I’ll see to it. Then you close your eyes and breathe more peacefully again. I wonder what you’re thinking? I wonder what your experiences were in this time you spent with us?

“A diary like this provides a short biography of what was happening around them,” says Storli.

Reduces post-traumatic stress

For many Norwegians the terrorist attacks of 22 July last year underscored how traumatic a stay in an ICU can be – how much one might have to contend with a long while after being hospitalised and close to death.

“But that was an extreme incident. A car accident can also be really hard to tackle, if you’ve had a head-on collision and someone has died next to you – that is certainly dramatic,” says Storli.

Diaries have been used in Norwegian ICUs since the 1990s and the recent recommendations are partly based on these experiences. New studies show that such diaries reduce patients’ post-traumatic stress symptoms.

These diaries usually include photos from the hospitalisation period and these too can be of great service.

At least two studies have shown that seeing pictures of yourself as an intensive care patient, particularly from the first days in the ICU, can help patients understand and accept that it takes time to convalesce after such an accident.

“These are recommendations that come from the ground floor – from daily nursing work. This isn’t something that has come down from the hospital management. Experience simply dictates that this is the best thing to do,” says Storli.

Personal, not private

The diary becomes part of the patient’s journal, so caution is called for out of ethical and legal considerations. The national recommendations specify clearly how the diary should be written, stored and delivered.

For instance the diaries should be personal – but not private. Endearing phrases such as “Dear…” or “A warm hug from…” are taboo.

Storli says now her research group wants to follow up the diary practice with studies of what is happening in the rehabilitation process of the patients.

“The diary is a start. It’s an opportunity to read a text. But then the patient has to be followed up further with human contact, where they can relate their experiences,” says Storli.

“We are now outlining a study for such follow-ups. For instance we want to see what it means for the patient to revisit the room they were hospitalised in. For many it can be an intense experience to hear the sound of a respirator once again. What does that do for you, and can it help you get on with your life after an accident? We want to find out such things,” she says.

-----------------------

Read this article in Norwegian at forskning.no

Translated by: Glenn Ostling