Study finds parents have cut back on giving their children sleeping pills

After concerns were raised about the practice, the use of allergy medicine to help one-year-olds sleep has been cut in half in Norway.

While the use of medication in Norway has increased over the last decade in the treatment of psychological problems in children aged seven to 18, the trend is exactly the opposite for Norway’s youngest children.

The reason is simple: Parents have greatly cut back on the use of an allergy medication called Vallergan. This medicine makes children relaxed and drowsy, which led to its use in roughly 3 per cent of Norwegian one-year-olds in 2004 as a sleeping aid. However, it has never been approved for use in children under two.

A welcome decline

Since then, parents’ use of this drug for their children has more than halved, according to a study from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and Hedmark University College.

“This suggests that parents and doctors have taken warnings about the drug seriously,” says Ingeborg Hartz, a researcher at both the NIPH and Hedmark University College.

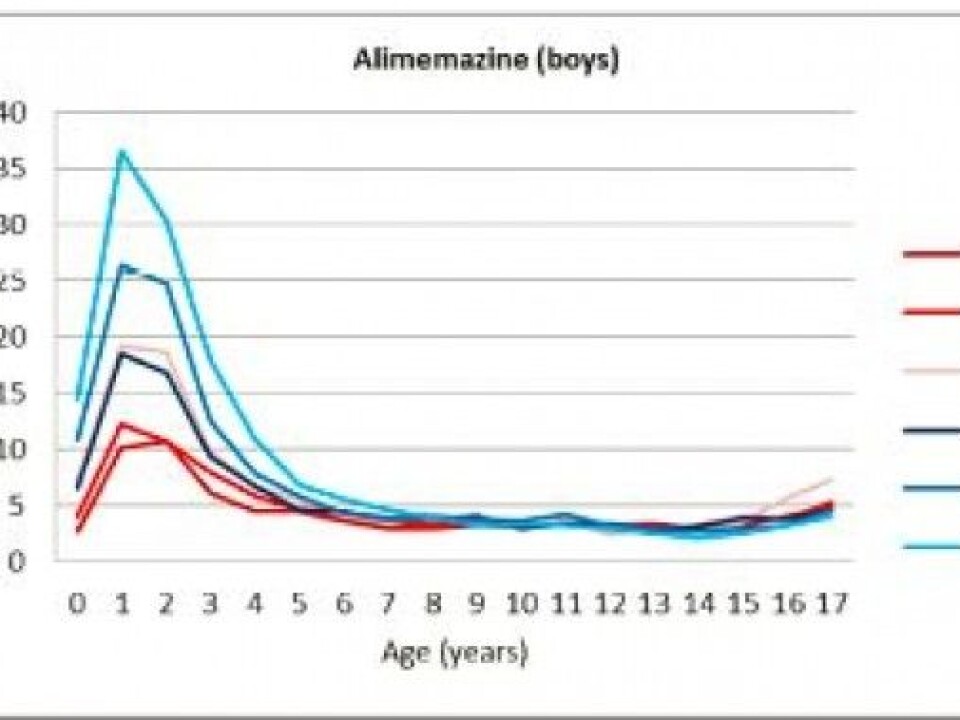

In 2004, 3.5 percent of one-year-old boys were given Vallergan as a sedative before bedtime. That amounts to about a thousand children.

Since then, its use has declined every year in the two-and-under age group. In 2014, the drug was given to just one per cent of one-year-old boys, according to an analysis of the use of prescription medicine for psychological problems among children and adolescents based on the Norwegian Prescription Database.

“This is a very welcome development, and may perhaps be due to an increased focus on the amount of use until 2004, as was demonstrated by figures from the Prescription Database,” said Hartz, who was one of the researchers involved in the study, recently published in BMC Psychiatry.

There has also been a corresponding decrease in the use of these drugs among young girls, aged one to two. Here usage fell from 2.5 per cent in 2004 to less than one per cent in 2014.

Worrying use

In 2008, an article in the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association described the use of Vallergan among young children as worrying. The article also outlined the serious side effects that can be associated with the drug.

Additionally, the drug remains in the body for a long time, up to 18 hours, and can cause drowsiness, headache and dizziness a day after it is used. There were also reports of serious complications in children.

The journal article also pointed to a study that concluded the drug could not be recommended as a sleep aid for children because it was neither safe nor effective.

More hormonal sleep aids for older children

The BMC Psychiatry study also found that there has been an increased use of sleeping aids in older children and adolescents in the same 10-year period. Norwegian parents have sharply increased their use of the hormone melatonin in children older than six.

Despite the fact that melatonin is not recommended for use in children and adolescents younger than 18, there has been an annual increase in use in this age group since 2004.

“When children are first put on melatonin, it appears that they are likely to use the drug over the course of several years, without us knowing anything about the long-term effects of its use,” Hartz says, a trend she describes as “worrying”.

Half of all children who start taking melatonin when they are between 4-8 years old are still using the drug three years later, Hartz says.

In Norway and the EU, melatonin is actually only approved for short-term use to treat insomnia in people older than 55.

Helping children sleep without the use of drugs

Mari Hysing, a research at Uni Research Health, says parents have different options to help their children sleep without having to rely on medication.

She suggests parents begin to establish good bedtime routines when a child is about 6 months old, which is about when babies are just beginning to have the physical characteristics that enable them to sleep through the night.

Children should not be allowed to sleep too much during the day, she says, and they should also be exposed to daylight, which has a positive effect on natural melatonin production.

“Make sure your child is tired, well-fed and happy before you put him or her to bed. Create a fixed ritual, by giving your child a little food, or reading or singing a little, preferably at the same time each night,” says Hysing.

If parents establish good routines and take other steps to help their child sleep but continue to have problems, Hysing recommends that they consult their doctor for advice and help.

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no