Frozen ovarian tissue restores women’s fertility

Doctors removed ovarian tissue from women about to undergo chemotherapy – and when it was transplanted after chemo, patients were able to become pregnant.

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

Chemotherapy works by killing malignant cancer cells – but in doing so, it can also damage healthy cells – including the egg follicles in a woman’s ovaries.

Yet as more and more young people are cured of what were once fatal cancers, doctors are working on ways to preserve a woman’s fertility after chemotherapy.

Tom Tanbo, a medical doctor and adjunct professor at the University of Oslo and his colleagues have now reported success with harvesting, freezing and transplanting ovarian tissue samples in women who have been treated for cancer.

Two of the women in the study gave birth to healthy children after the previously frozen tissue was re-implanted.

Strict guidelines for selection

The first births in women who have undergone this type of treatment occurred in 2004 in Belgium. That same year, lawmakers changed Norway’s Biotechnology Act to make it legal for Norwegian gynaecologists to offer the treatment.

The protocol is offered in Norway to women 35 years and younger if they have a localized tumour or a non-malignant disease, while the upper age limit for women with systematic diseases like leukaemia is 25.

“Older women are at greater risk of chromosomal abnormalities in eggs and generally have fewer eggs in their ovaries. That is why we have set the upper age limits,” Tanbo said.

Not all cancers are amenable to the procedure, however, Tanbo said. For example, the researchers have to be certain that malignant cells have not spread to the ovaries.

“If they have, then we risk transplanting these cells back into the body with the ovarian tissue after the patient has been successfully treated for cancer,” he said.

164 samples, two transplants

Since the procedure was made legal in Norway 11 years ago, doctors have taken 164 ovarian tissue samples under the protocol.

However, only six of the women whose tissue was frozen were interested in the procedure after their chemotherapy, and of these, only two women actually met all the requirements and had the tissue re-implanted. Tanbo and his colleagues describe possible reasons why so few women asked for the procedure in a paper just published in Acta Obstretricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica.

“Possible causes for the few replacement requests may be resumption of spontaneous fertility after treatment, age of the patient, no desire to become pregnant, no partner, or short observation period,” the researchers wrote.

Small squares carefully frozen

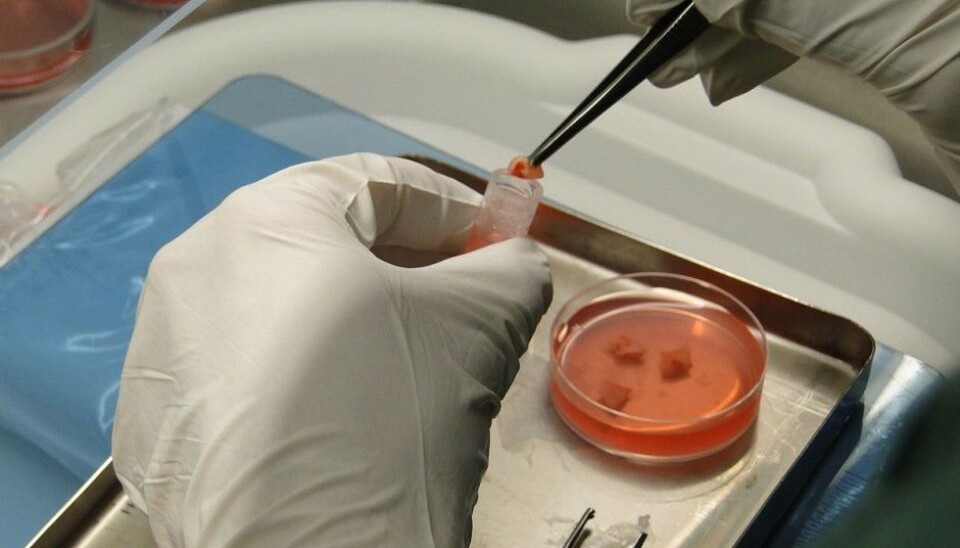

The procedure involves removing one of a woman’s two ovaries. Doctors then cut out small squares of tissue from the harvested ovary, roughly 5 centimetres on a side and just a millimetre thick.

These tissue squares are then carefully frozen – which is the most critical part of the entire procedure. Doctors use more or less the same process that they have used over the last 30 years to freeze a woman’s eggs.

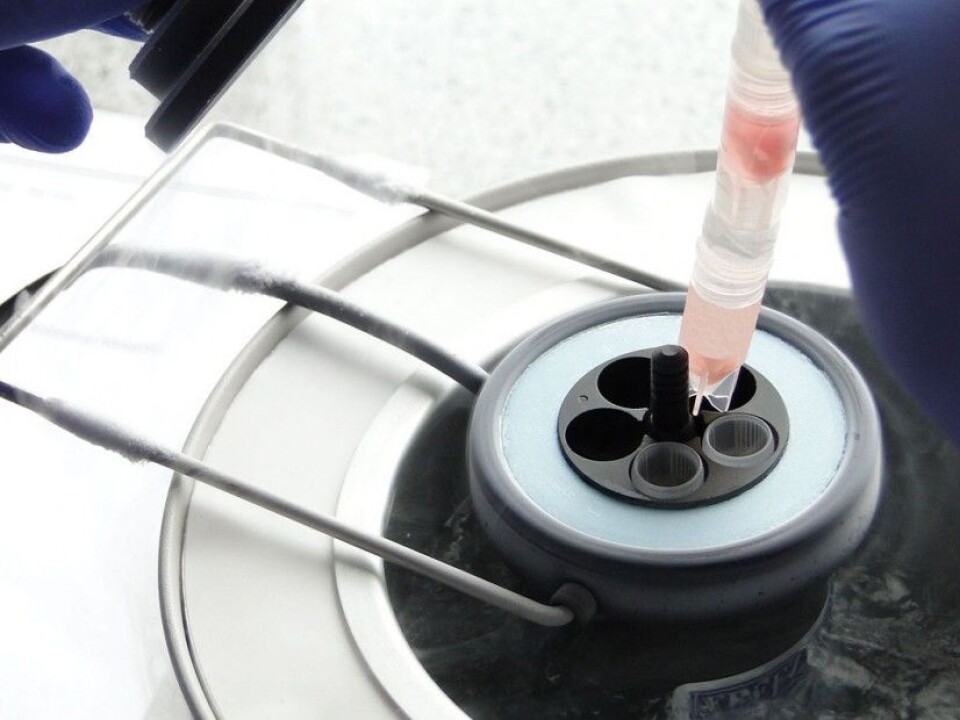

Stored in liquid nitrogen after the careful freezing process, the tissue is theoretically viable almost indefinitely.

“All we have to do is to make sure that we keep the liquid nitrogen at the right level, because it can evaporate slowly,” Tanbo said.

Keyhole surgery

Replacing the harvested tissue involves a type of keyhole surgery. Doctors go in with a tube through a small hole in the patient’s stomach. The woman’s remaining ovary is opened lengthwise. One or more tissue samples are placed into the ovary, and it is then stitched up.

“It is not critical exactly where in the ovary the tissue samples are placed,” says Tanbo.

Tanbo and his colleagues say while some patients have actually become pregnant without the transplant, they have good reason to believe their two success stories can be attributed to the treatment.

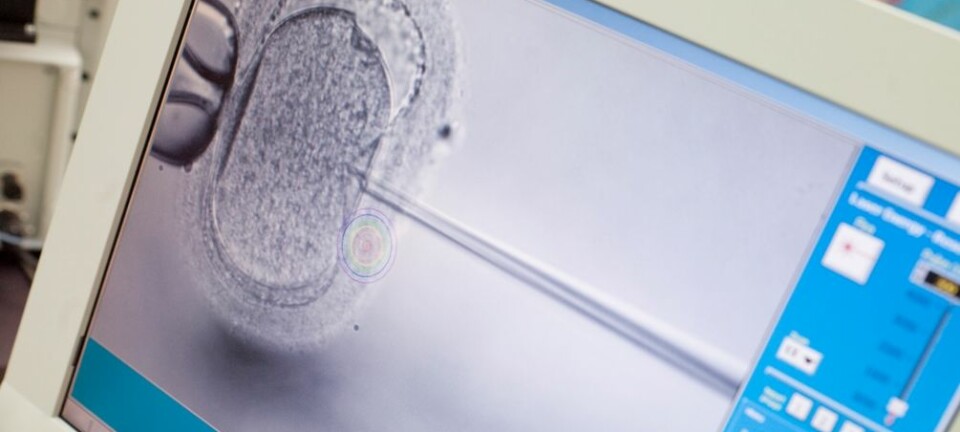

In one case, they are absolutely certain, because the woman in question underwent two attempts with in vitro fertilization because her partner’s sperm quality was low. Only after these attempts failed did the woman have her ovarian tissue re-implanted. She subsequently conceived successfully via in vitro fertilization.

Although not many women have chosen to have the procedure after their cancer treatment, Tanbo believes that it is important to offer them the opportunity.

For individuals in this situation, it may be very important for them to have children, he said.

----------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no