This is how your immune system's memory works

How can your body's defence forces recall previous attacks?

It happens all the time. When you accept change, pick up your kindergartener or travel to the Canary Islands. You’re under attack. Continuously.

It all takes place on a microscopic level. Microbes, like bacteria and viruses, love to find you and make you their home. Intense fighting goes on between your immune system and the unwanted microbes. And usually you don’t notice a thing.

Presumably this is because your defences are acquainted with the intruder from before and know exactly what to do to get rid of it. Rooting out the troublemaker generally happens quickly, efficiently and virtually painlessly.

So how is the body able to recognize an enemy that it has fought off before? Does our immune system really have a memory?

The B cells and the T cells

Anne Spurkland is a Professor in the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences at the University of Oslo, and probably more interested in the immune system than most of us. In addition to her research in the field, she even blogs about it in her free time.

In simple terms, she explains how the immune system can recognize unwanted intruders from previous attacks.

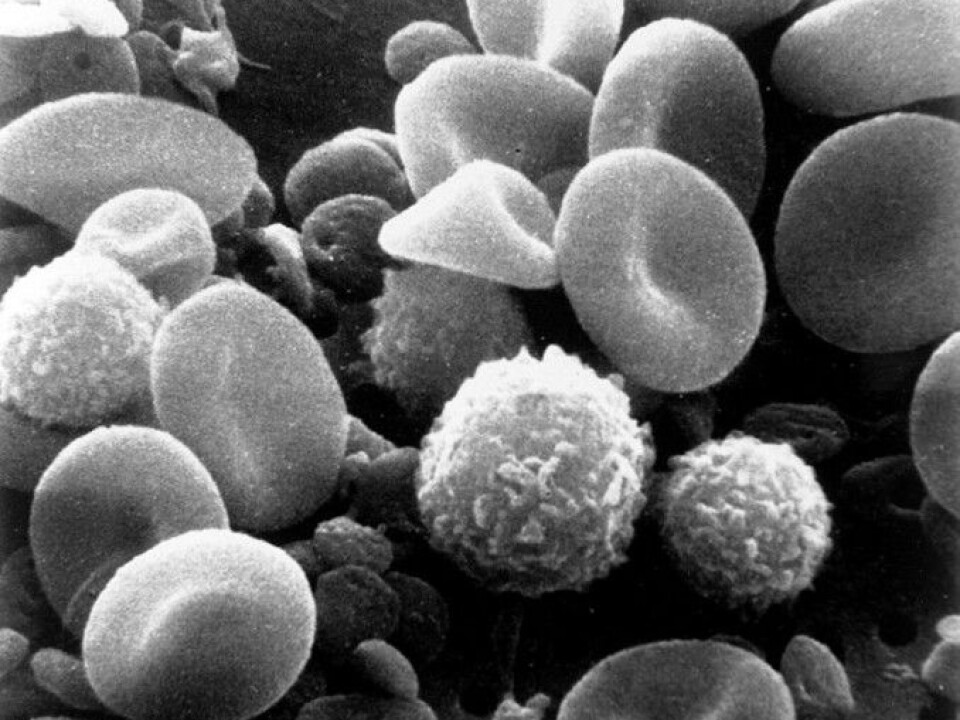

Basically, two types of cells build up the immune system's memory.

“It starts with two types of white blood cells: B cells and T cells. We have millions of these cells in our bodies. And each of them has its own unique receptor,” she tells forskning.no.

The receptor enables each cell to respond to a particular kind of bacteria or a virus. When unknown bacteria attack your body for the first time, only about 50 to 100 cells have the ability to respond to this exact type of attack.

This signals the start of an epic battle, and the consequences may well be a week's sick leave for you.

Bacteria go in for the attack

Let's say that a certain type of bacteria has found its way in, past the body's defensive outer wall, the skin and mucous membranes. This is where B cells step up to the forefront. T cells help the B cells and can also take on any viruses.

The B cell receptor binds to the bacteria and starts dividing. This builds up the special defence squad, which was initially quite small, and adds more battle-ready soldiers. The soldiers begin to create antibodies against the bacteria, which the blood transports throughout the body.

The antibodies react to the bacteria and signal to various killer cells, like macrophages, that they can eradicate the foreign microbes. Antibodies also often neutralize toxins that certain bacteria secrete.

“Every time cells divide, their receptors — and the antibodies they create — are a better fit against that particular microbe. The original receptor adapts itself,” says Spurkland.

And so the struggle continues until the alien microbe is eradicated.

“When the microbe is gone, the immune cells are no longer stimulated and most of them die. Otherwise, too many cells would build up in the body.

But not all the cells vanish.

War veterans on patrol

“A few days after the infection is over, fewer of these immune cells remain, but there are still more than before the body was attacked,” she says.

These remaining cells are called memory cells. They’ve been at war before and can recognize the enemy if it returns.

When that happens, “several more cells are able to recognize the invading microbe. And this time, they respond faster. We've become immune. The next time the cells meet the microbe, they’re faster yet and the battle is all over in a day or two. Maybe we don’t even get sick,” says Spurkland.

This cell memory, it’s important to point out, is only valid for exactly this specific infection. The immune system in general does not get "stronger" by you being sick.

Memory doesn’t allways last forever

Vaccines are used to trigger this memory function, so that memory cells can recognize bacteria and viruses that are a danger to us. But why is it that you sometimes have to return to the doctor for a booster?

“The cell memory doesn’t last forever, especially against microbes that don’t occur naturally where we live,” says Spurkland.

Another problem is that microbes change all the time, while the immune system is quite stable. “When microbes come around that we’re not at all prepared for, an epidemic may break out. The immune system simply can’t adapt quickly enough to the new microbe,” she says.

In 2015, the journal Science published a new study that found that measles can destroy the immune system's memory. This could result in you being more vulnerable for other diseases that you had been immune to.

Attacks the body

There is no doubt that our immune system is good to have. But flawless it’s not.

Spurkland says, “The immune system has to keep track of what is the body's own tissue and what is the microbe. If the microbe strongly resembles our tissue, the immune system may also attack the body.

Autoimmune diseases are examples of when your immune system thinks your body is an intruder.

“Normally the immune cells disappear when the target intruder is destroyed, but your body can’t be eradicated as long as you’re alive,” says the researcher

-------------------------------------

Read the Norwegian version of this article at forskning.no